Reason: (5th) On Variability, Probability, and the Illusion of Prediction

Why Mathematical Descriptions of Unstable Systems Mislead More Than They Reveal

APPENDICES

Appendix A – Mathematics, Language, and Hidden Patterns

Mathematics as Language

We have to keep in mind that mathematics is a form of language. Language is used to describe the world, but it is not the world itself. Mathematics, no less than ordinary language, is a symbolic system for description, not the thing described.

Whereas many patterns in the world are visible and can be recognized directly—waves breaking on a shore, leaves falling in autumn—probability deals with patterns that are hidden. These are not readily observable but must be inferred.

One useful analogy comes from signals, information, and signal detection. Patterns may be buried in noise, invisible to the naked eye, but methods of analysis can reveal their presence. Similarly, probability and mathematics allow us to uncover structures that lie beneath the surface of variability. We can test these methods, compare results, and show that they work, even when the patterns themselves are hidden.

Mathematics and Natural Language

Any mathematical result, calculation, or formula can be expressed in natural language. The symbols of mathematics—its notation, operations, and orthographic devices—are only shorthand. To understand them, they must be explained in words. And once they are explained, they can be grasped tacitly, without the symbols.

Every mathematical operation has a verbal description in natural language. This point may seem obvious, but it is often overlooked, even by those highly trained in mathematics. The language of mathematics appears to stand apart, but it always depends on ordinary words for its interpretation.

Language, in all its forms, is an attempt to describe the world through symbols. We will leave “symbol” undefined here, but note that mathematics is a language—different in form and more tightly constrained, but a language nonetheless. Everything in mathematics can, in principle, be expressed in natural language.

The Asymmetry

The reverse, however, is not true. Not everything in natural language can be expressed in mathematics. Natural language is broader, looser, and more flexible. It can capture nuances, ambiguities, and lived experience that mathematics cannot formalize.

This creates an asymmetry: mathematics is a subset of language. It is precise, formal, and powerful within its domain, but it cannot encompass the full scope of natural language. The relationship is one of subsetting: mathematics fits inside language, not the other way around.

Appendix B – Variability, Language, and the Dual Sense of Probability

Variability as the Ground

The world is governed by variability. No two things happen exactly the same way, no two outcomes are identical in all respects. Some of this variability can be described in the language of probability. But once we invoke that language, we encounter a subtle distinction: probability seems to carry two different senses.

Two Senses of Probability

The first sense belongs to the world itself. The world contains variability—dice tumble in unpredictable ways, the wind shifts, raindrops fall at irregular intervals. This variability can be described in ordinary language: “The die came up six,” “The wind changed direction,” “The rain fell hard in the morning and lightly in the afternoon.” These words work well enough. They point to real features of experience.

The second sense belongs to the formal language of probability. Here, we use ratios, distributions, and frequencies to summarize variability in patterns: one-sixth for the die, 60% chance of rain, a normal distribution of heights in a population. These probabilistic words and symbols describe patterns of variability, not the variability itself. And, like all words, they have their limits. They are applicable in some situations, and not in others. The crucial question is always: when does the language fit, and when does it not?

Probability and the Nature of Words

To make the point clearer, consider the difference between ordinary words and probabilistic ones. With ordinary language, I can invent a word—say, “jiplicky”—and if I define it to mean “the thing over there,” then that is what it means. Language allows such conventions.

But probability is different. I cannot simply invent “jiplicky” as a probability term and expect it to describe the world. Probability claims to describe patterns of variability: patterns of counts, measures, and frequencies. To say something is “jiplicky” as a probabilistic pattern would mean that it exhibits a particular kind of statistical regularity. That requires evidence, not just convention.

Patterns and Their Limits

Probability, then, is a language for patterns—specifically patterns of repeatability, frequency, and distribution. It works when those patterns are stable and enumerable. But its use does not guarantee that the patterns it describes exist in the world in the way the formulas suggest.

For example:

· A coin, when flipped many times, produces heads about half the time. Here, probability captures a real, observable pattern of variability.

· A weather forecast might say there is a 70% chance of rain. But that number is not in the sky; it is a summary of past patterns under similar conditions. The variability is real, but the probabilistic expression is a human construct layered on top of it.

· A doctor might say there is a 30% chance a patient will survive five years. But the patient will either survive or not. The variability exists across populations; the number is a way of mapping that variability into language.

In each case, probability describes patterns, but whether those patterns actually apply to the next event—the single outcome that will occur—remains uncertain.

The Issue in Closing

So probability has this dual character. On one hand, there is the objective variability of the world, which we can describe with ordinary words. On the other hand, there is the specialized language of probability, which turns variability into patterns of counts and frequencies.

But the fit between the two is never guaranteed. Variability exists. Probability is our attempt to describe it. Whether the probabilistic description applies in any given case—that is always the issue.

Appendix C – The Situational Nature of Probability and Measurement

Probability as Situational

One of the key points worth emphasizing is that applied probability is always situational. It is never free-floating, never independent of context. We may speak casually of “fair dice” or “unbiased draws,” but what actually counts as an event, what counts as a situation, and what counts as an outcome—all of these are matters of definition and decision.

A dice roll is not an event until we define it as one. Do we mean the throw itself, the landing of the die, or the observation of the face after it comes to rest? Each definition frames the situation differently, and each leads to slightly different understandings of what the outcome is.

Measurement as Decision

The same logic applies to measurement and counting. Measurement is not something that exists in the universe in a Platonic sense, waiting to be uncovered. It is a human decision.

· Counting People: Are we counting adults only? Children as well? What about unborn children? What about visitors or temporary residents? The category “population” depends on decisions about inclusion and exclusion.

· Measuring Time: Do we mark days by the sun, the moon, or by atomic oscillations? Each measure is humanly chosen, though all reflect real rhythms in the world.

· Medical Outcomes: In a drug trial, do we measure “success” as reduced symptoms, as complete remission, or as longer survival? Each choice defines the outcome differently, and the probabilities calculated will follow that choice.

Measurement and counting are never automatic. They depend on what we decide to observe, how we decide to classify it, and what tools we choose to employ.

Language and the Frame of Thought

These decisions are carried out through language. We set up categories, name outcomes, and frame situations using words. While language is not identical with thought, it provides the scaffolding on which thought operates.

Probability, then, is doubly linguistic. First, because we define situations, events, and outcomes in words. Second, because the mathematics of probability itself is a formalized language—symbols, ratios, and distributions—all of which sit on top of prior linguistic decisions about what is being counted or measured.

The Broader Point

The universe does not present us with “events,” “outcomes,” or “measurements” pre-labeled. These are human constructs, stabilized through language and practice. Variability exists in the world, but probability is the language we use to talk about it, and measurement is the procedure we design to capture it.

Both probability and measurement are situational, and both depend on decisions about what matters, what counts, and what will be included or excluded. To forget this is to slip into reification—to treat probability or measurement as if they were properties of the world itself rather than descriptions shaped by human judgment.

Appendix D – Probability, Chaos, and the Limits of Description

Probability as Partial Description

Statistics and probability, when applicable, do not describe the world itself. They describe certain features of the world, features carved out by how we define situations, events, and outcomes. What they provide is not the world in its entirety, but a selective description of particular aspects.

We can use the language of probabilities to describe these features. The larger question is whether probability can be stretched to describe all features of the world.

Chaos as an Alternative

Many have argued that large domains of the world are better approached through chaos mathematics. But chaos mathematics is no more a full description of reality than probability is. It does not describe systems in detail; it only says, “here is a pattern that resembles another pattern.”

Chaos theory also emphasizes instability: outcomes depend on ephemeral factors, small variations magnified over time. This is the so-called butterfly effect, where the flap of a wing shifts the trajectory of a storm.

But here too, the mathematics does not describe a particular pattern in the concrete sense. It does not say what will happen. It shows only families of patterns, just as probability points to long-run distributions without predicting individual outcomes.

Different mathematics, different uses, same limitation.

Applying Statistics to Open Systems

At some point, statisticians began applying probabilistic language—these linguistic devices and models—to open systems where outcomes cannot be fully enumerated. These are unstable systems: nonlinear, confounded, and influenced by countless interacting variables.

Nevertheless, some pressed ahead. Concepts such as the central limit theorem and related results were extended to medicine, psychology, economics, and other unstable fields.

But whether such systems truly conform—even “in the long run”—to theoretical probability distributions is another matter entirely. There is no guarantee that they do. Still, the practice persists.

The Question of Legitimacy

Some scholars insist this extension is illegitimate. Others accept it pragmatically, noting that probabilistic models can sometimes be useful even if their theoretical grounding is doubtful. Either way, the critical point must be remembered:

· These calculations say nothing about any given individual event.

· They describe only aggregates, and only insofar as the model is accepted.

But are the models—the toy worlds—truly applicable to open systems? That remains uncertain. In unstable domains, we have no reliable way of knowing whether the models match reality.

Appendix E – Variability and the Reification of Probability

The Temptation to Reify Probability

There is a recurring tendency to treat “probability” as if it were more than a language—as if it were a real thing, a Platonic entity existing in the world itself. This reification slips easily into everyday thought: people speak of the “probability of rain,” the “probability of survival,” or the “probability of winning” as though probability were an invisible substance that governs outcomes.

But probability is not a force in the world. It is a way of talking about variability, a framework for describing uncertainty. To reify it is to mistake a linguistic device for an ontological fact.

Variability as a Real Feature

By contrast, variability itself is not an illusion. It is an evident and undeniable feature of the world. Dice do not always land the same way. Leaves do not fall in identical patterns. No two human bodies are the same, and no two medical cases unfold in precisely the same fashion. The world is filled with variability.

Where conditions are constrained and outcomes enumerable—such as coin flips or card draws—the language of probability seems to capture variability with remarkable precision. In such cases, the mapping between mathematics and observed outcomes is tight. The model holds up.

Examples of Where Probability Works

Consider games of chance:

· A fair six-sided die has six possible outcomes. Over many throws, the distribution of results aligns with the expected one-sixth per side. Variability is real, but its long-run pattern is captured by probabilistic description.

· Similarly, a shuffled deck of cards yields a well-defined space of possible hands. The probability of drawing a flush in poker can be calculated exactly. Variability in card play is genuine, and probability provides a faithful description of it.

In these examples, probability is not “out there” in the world. It is our way of describing how outcomes vary within a constrained, well-defined system.

Examples of Where Probability Is Reified

Contrast this with situations where probability is reified, and the language begins to mislead.

· Weather Forecasting: When a forecast says there is a 60% chance of rain tomorrow, what does that mean? It does not mean that “probability” exists in the clouds. It means that in past, similar atmospheric setups, rain occurred 60% of the time. The variability is real, but the “60%” is a shorthand for aggregate history, not a property of tomorrow’s sky.

· Medical Prognosis: When a doctor says a patient has a “30% chance of surviving five years,” probability is invoked as though it were a property of the patient. But the patient will either survive or not. The number reflects population variability, not individual destiny. Yet many patients hear it as a statement about their own fate, as if probability resided inside their body.

· Stock Market Predictions: Analysts sometimes speak as if future market swings have probabilities built into them, waiting to be uncovered. But the market is an open, unstable system. The numbers represent patterns found in past data, not a hidden probabilistic essence in tomorrow’s trades.

In each of these cases, probability becomes reified. What should be understood as a descriptive framework for aggregate variability is taken as a concrete feature of individual events.

Why This Matters

The distinction matters because once probability is reified, it is easy to slip into unwarranted confidence. A patient may despair or rejoice over a probability figure that says nothing definitive about their case. A policymaker may believe that probabilistic risk models describe the future when in fact they only describe the past.

Recognizing that variability is real but probability is a human description helps avoid this error. Probability is not a law of nature or a property of things. It is a language we impose to summarize patterns of variability, and it works only in situations where the assumptions that ground it are secure.

Appendix F – Variability in Ballistics

Accuracy, Precision, and Probabilistic Description

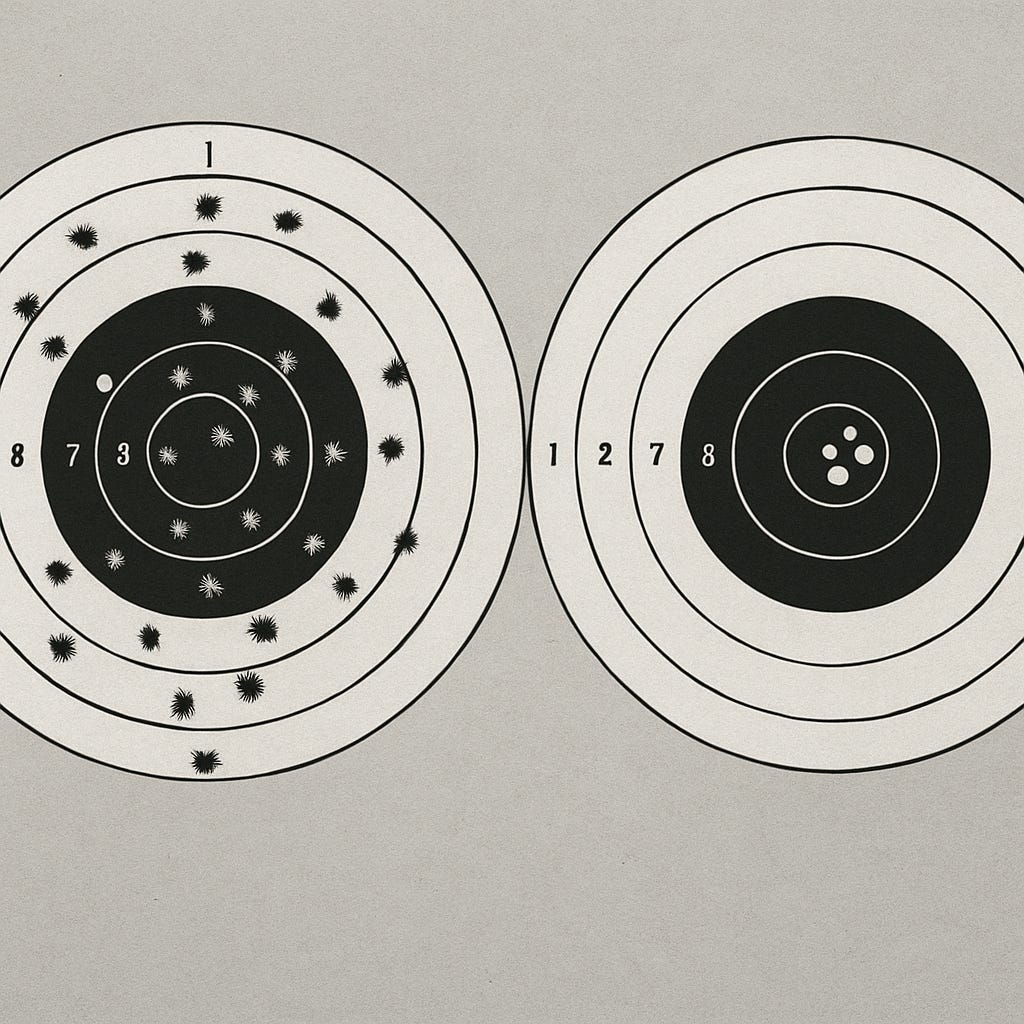

Ballistics provides a practical and vivid case where variability is central. Consider the act of shooting bullets at a target. The outcomes are immediately visible, and over time, they form patterns that can be described in probabilistic terms.

Two technical concepts are standard in this domain:

· Accuracy refers to how close the average of the shots comes to the bullseye. A shooter who consistently places rounds near the center of the target is accurate.

· Precision refers to how tightly grouped the shots are, regardless of whether they are near the bullseye. A shooter might be imprecise but accurate (shots spread widely but centered near the bullseye), or precise but inaccurate (shots clustered tightly, but off to the side).

These distinctions are not just semantic; they are operational. They allow instructors, engineers, and analysts to classify the performance of both shooters and firearms.

In this case, probabilistic language has clear value. The spread of shots can be described statistically, with measures of central tendency and dispersion. Distributions of impacts can be tested, compared, and improved upon. Unlike in unstable systems such as psychology or nutrition, here probabilistic models have teeth: they describe variability in ways that are empirically testable and operationally useful—for designing weapons, training shooters, or estimating error ranges in combat or hunting.

Situational Dependence in Ballistics

Still, the picture is not as clean as the mathematics may suggest. Accuracy and precision depend on many situational factors:

· The shooter—their steadiness, skill, and fatigue.

· The firearm—its weight, barrel length, and maintenance.

· The ammunition—manufacturing tolerances, powder loads, and bullet design.

· The environment—distance to the target, crosswinds, humidity, and temperature.

Each of these contributes to the variability. To talk meaningfully about accuracy or precision, one must first specify what is being evaluated. Are we talking about the mechanical accuracy of the gun itself, measured in a machine rest? Are we judging the skill of the shooter, with all human frailties included? Or are we talking about the combined system—shooter plus weapon plus environment?

Probabilistic models can summarize variability in each case, but the situation has to be defined. Without that definition, the numbers float free, and “accuracy” or “precision” become misleading generalities.

Defining Events and Outcomes

In ballistics, the definition of an event and its outcomes is straightforward at the surface level:

· Event: a single shot fired at a target.

· Outcome: the location of the hole in the target.

From there, however, complexity quickly arises. Do we measure outcomes in terms of radial distance from the bullseye? In angular minutes of deviation? In the size of the group formed by multiple shots? Each measure is valid, but each reflects a decision about what counts as the relevant outcome.

For a competitive shooter, the key measure may be how many shots land within the ten-ring. For a military sniper, it may be whether the shot falls within the “vital zone” of a target at long range. For a hunter, it may be whether the shot is effective in practice, not whether it scores tightly on paper. Each definition frames accuracy and precision differently, and each frames the probabilistic description differently.

Situational Judgments and Practical Uses

The variability in ballistics demonstrates both the strength and the limits of probabilistic reasoning. It is a domain where probability does meaningful work—shot patterns can be aggregated, distributions can be drawn, and predictions about likely hit zones can be made. But those predictions are always conditional on how the situation is defined.

For example:

· A rifle tested in a machine rest with match-grade ammunition may show precision measured in fractions of a minute of angle. That precision belongs to the rifle-ammunition system, not to the human shooter who will later fire it.

· A soldier firing under stress, with poor sleep and heavy gear, introduces a new level of variability. The pattern of hits reflects not only the firearm but also fatigue, stress response, and body mechanics.

· A hunting rifle in the field faces changing wind, rain, or temperature. The variability introduced by weather may swamp the firearm’s inherent precision.

In every case, the probabilistic language remains valid, but only for the situation defined. Accuracy and precision are not absolute features; they are situational descriptors.

The Broader Point

The lesson from ballistics is not that probability always works, but that in certain constrained and well-specified domains, it works pragmatically. Ballistics gives us a case where events and outcomes can be defined cleanly, where variability is visible, and where probabilistic models produce operationally useful descriptions.

But even here, the key is situational framing. We must decide whether we are measuring the shooter, the weapon, the ammunition, or the environment. We must decide what counts as success, and what counts as error. These decisions are human, not mathematical. The numbers that follow are tethered to those judgments.

The Complete Series:

1st: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-1st-on-variability-probability

2nd: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-2nd-on-variability-probability

3rd: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-3rd-on-variability-probability

4th: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-4th-on-variability-probability

5th: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-5th-on-variability-probability