Reason: (2nd) On Variability, Probability, and the Illusion of Prediction

Why Mathematical Descriptions of Unstable Systems Mislead More Than They Reveal

PART III – GOING OFF ON A TANGENT

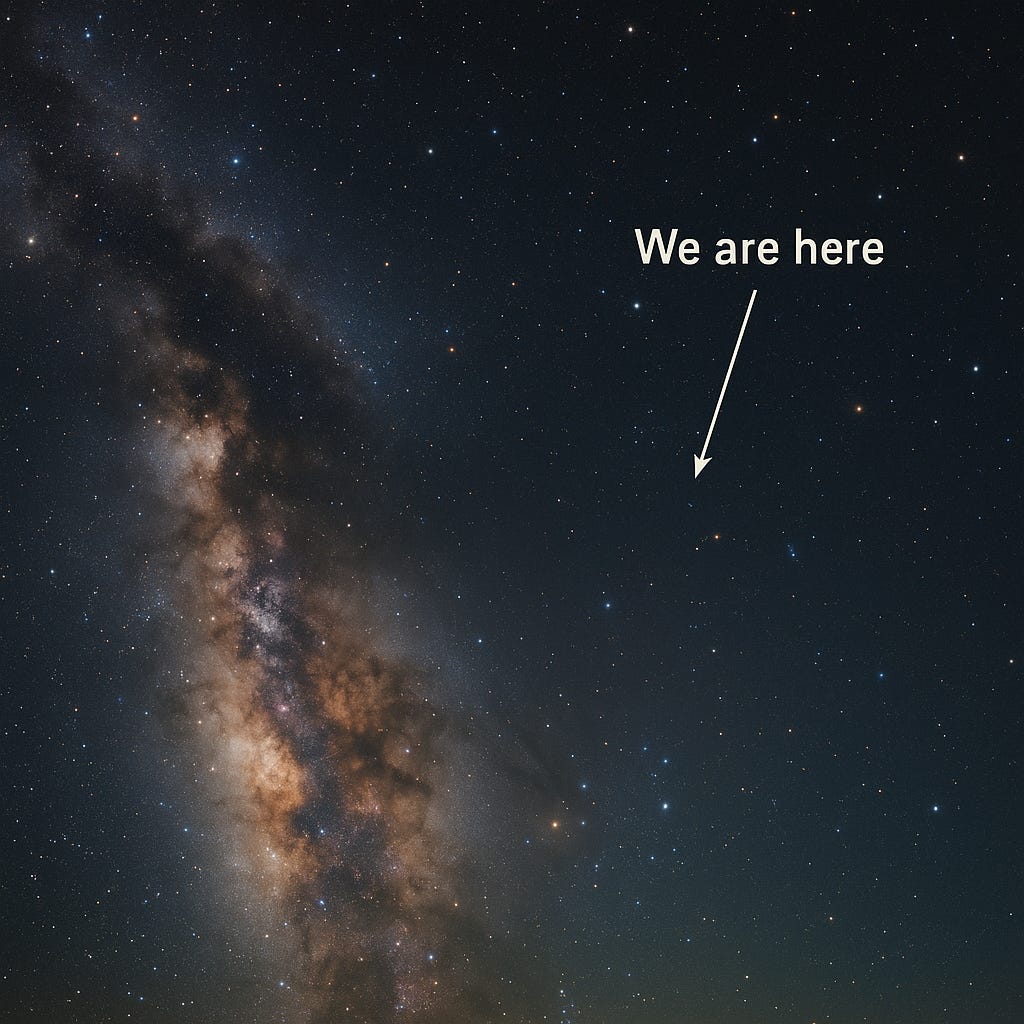

Going Off on a Tangent and Playing With a Model of the Universe

Here’s a model:

We have the universe. We assume it is objective and deterministic, and that there is causality. At time 0, it is in state 1. At time 1, it is in state 2.

What happened between time 0 and time 1? Did it go through infinitely many states? Is that even meaningful? It is certainly not falsifiable. Certainly not verifiable. Certainly not knowable.

Who said understanding the universe was going to be easy? It is just a model. Get over it. In any case, we do not have to understand the whole universe, only our corner of it.

Limits of Understanding the Universe

We only ever understand the universe locally, through our senses and through our tools. But both senses and tools show us things only as they were in the past. Even when something is brought to our senses “immediately,” it is still past tense. We are hemmed in by the speed of light.

Things, Events, and Causality

So we talk about things and events. Things are abstractions of local states. Events are changes from one state to another.

Sometimes causality is visible. At other times, all we see is variability. We call that randomness. But randomness has two faces: an epistemological one (a measure of what we know and don’t know) and an ontological one (a claim about what exists). I prefer the epistemological over the ontological.

The Problem of Uncaused Events

Under the normal rules of thought and language, to assert that some event is uncaused yet still shows structure is self-contradictory.

To get around that, one must say not only is the universe stranger than we suppose—it is stranger than we can suppose. I cannot conceive how something could be uncaused, yet still display structure, regularity, or pattern, no matter what label one applies.

1: J. B. S. Haldane, Possible Worlds and Other Essays (1927), essay “Possible Worlds”:

“Now, my own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose. I suspect that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of, or can be dreamed of, in any philosophy.”

PART IV – THE LIMITS OF CONTROL AND PREDICTION

Intuitive Predictions and Belief in Luck

Unstable as outcomes may be, we can still make intuitive—tacit—predictions, and often with success rates better than fifty-fifty.

Human beings have long had a language for this. In earlier times, predictions were credited to gods or spirits. Today, in most cultures, that attribution is rare, though it persists in some quarters. Instead, people may speak of “luck,” as if it were a principle woven into the universe that governs their fate. People, after all, believe many kinds of things.

Knowledge, Control, and Prediction

With language—limited as it is—and with our own wetware—also limited—we try to describe variability, causal factors, and the possibility of prediction. The effort ties us into linguistic and conceptual knots, yet language is the only tool we have.

The general rule seems clear enough: more knowledge usually improves prediction. If we had perfect knowledge of a local situation, prediction would no longer be probabilistic at all; the probability would be 1.

Control matters too. If we can not only know but also influence the state of a situation, we can reduce uncertainty further. With full knowledge of the controls, and the ability to apply them, the probability again becomes 1.

Control and the Limits of Prediction

Prediction, then, depends on knowledge of control. Control can reduce variability, but the ability to predict depends on how well we understand the controls themselves. Without that, even partial control does not guarantee reliable prediction.

The Limits of Probability

Probability requires variability. If there is none, then probability collapses into certainty. But when variability is too great—when instability is high, or when the possible outcomes cannot even be enumerated—the model itself begins to break down.

Nonlinearities, feedbacks, and confounding factors can make it impossible to define the situation adequately. Each case may differ too much from the last. In such contexts, probability may simply be the wrong language—an inappropriate way of framing what is happening.

Probability as Abstraction and Idealization

We have developed the language of probabilities to describe the material world—classifying situations, events, and outcomes. In some specific, stable contexts, the probabilities attach neatly to what we observe.

But we also build imaginary “toy worlds” that are tethered to reality only loosely. These are idealizations: simplified structures that make the mathematics tractable. We then make a leap and claim that these abstractions not only come from the physical world but apply back to it. To that, I respond: prove it.

In some stable domains, the claim holds up. If the type of event, the surrounding situation, and the possible outcomes can all be specified, then probability works—empirically, in the long run. Dice, coins, and cards provide familiar examples.

But even there, the “long run” remains vague. It may mean infinity, 100,000 trials, or 5,000 events. Who knows? It is always an idealization.

Practically, we can sometimes run 5,000 trials and confirm that the pattern approximates the predicted frequencies. That counts as empirical confirmation: probability seems to work in describing aggregates. But it does not erase the fact that the structure is an abstraction, verified only in certain stable situations, and never beyond them.

PART V – PROBABILITY AND UNSTABLE SYSTEMS

When Probabilistic Language Works

Probabilistic language works reasonably well when outcomes can be clearly listed—enumerated if one prefers—where conditions are stable and controlled, and where both the situation and what is being counted or measured are well defined.

Under those circumstances, the rules of probability function adequately. They do not predict individual outcomes, but they allow us to estimate the likelihood of outcomes in the long run.

Do Applied Probabilities Only Pertain to Defined Situations?

We use probability to describe particular situations. Take card draws as an example: we can specify the setup precisely, define the events clearly, and calculate the probability of each outcome.

But this is not a purely mathematical abstraction. It is a physical situation. The setup must be defined, the events must be defined, and the outcomes must be defined. Only then can we speak coherently about probabilities.

So probability always requires a return to first principles: what is the situation, what counts as an event, and what are the possible outcomes under that arrangement?

Assigning Probabilities to Unstable Events

Even so, we like to assign probabilities to unstable events, and sometimes the effort appears to have success. But it is rarely numerical success in the strict sense. The assumption that mathematically precise numbers can be applied to unstable domains is probably mistaken. It has never been proven.

By “numbers” I mean mathematically tractable distributions. We can count outcomes after the fact—once we decide what the situation is and what counts as an outcome. But that is retrospective. We can count what happened. That does not mean we can assign genuine numerical probabilities to what might happen.

A Case in Point: Nutritional Research

Nutritional research illustrates the problem. Studies routinely report that eating a particular food “reduces the probability” of developing a disease by some percentage. But what is the actual situation? What is the event? And what counts as an outcome?

Human diets are not closed systems. They are endlessly variable—shaped by genetics, culture, lifestyle, environment, and chance. No two diets are identical, and no two bodies metabolize food in precisely the same way. Confounding factors abound: sleep, exercise, stress, pollutants, and social habits all interact with diet in ways that cannot be cleanly separated.

So when researchers assign a number—a “20 percent reduced risk” of cancer, say—they are not reporting a true probability in the sense of dice or cards. They are reporting group-level frequencies, abstracted from unstable systems, and presenting them as if they were probabilities. The assumptions that make probability work—closure, stability, identical distributions—are not in place.

The numbers create an aura of scientific precision, but they are really placeholders for patterns that may or may not hold beyond the studied group. In this sense, probability functions more as a rhetorical device than as a faithful description of reality.

Another Case: Stroke Risk

The same issue appears in medicine. Take the example of being told, after a stroke, that the “odds” of having another stroke within a year are fifty-fifty. What is the situation here? What is the event? And what are the possible outcomes?

The figure comes from group averages—counts of how often certain patients in some study had recurrent strokes. But those numbers do not translate into a probability for any one individual. Bodies are not closed systems; they are unstable, open to daily change. Diet, stress, sleep, exercise, genetics, and innumerable unknown factors shift constantly. To assign a single probability—50 percent—is to compress this variability into the metaphor of a coin flip.

That may sound authoritative, but it is misleading. The probability offered is not a prediction about an individual body; it is an aggregate summary applied as if it were one. The underlying meta-assumption—that a group frequency translates into an individual probability—is unwarranted.

What can actually be said is simple: another stroke may happen tomorrow, or in ten years, or never again. Counting what has happened to groups in the past does not allow numerical prediction of what will happen to an individual in the future.

The Broader Point

Nutrition, medicine, epidemiology, economics—the pattern is the same. In unstable, open systems, the temptation to assign precise numbers masks the fact that the situation itself cannot be defined in the way probability requires. At best, we can count what has already happened. But the leap from retrospective counting to prospective numerical prediction remains an act of faith.

The Complete Series:

1st: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-1st-on-variability-probability

2nd: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-2nd-on-variability-probability

3rd: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-3rd-on-variability-probability

4th: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-4th-on-variability-probability

5th: https://ephektikoi.substack.com/p/reason-5th-on-variability-probability