Chapter 4: Learning to Work with Premises

From: Reason: Thinking Without Guarantees: A Guide to Some Reasoning Heuristics

For context, see:

Reason: Thinking Without Guarantees: A Guide to Some Reasoning Heuristics

Chapter 1: What Reasoning Is and What It Is Not

Chapter 2: Connecting Reasoning to Direct Observation

Chapter 3: Building Internally Consistent Narratives

4.1 How Do We Know a Premise Is True?

Premises are where reasoning begins. They are the statements or assumptions we treat as true for the purpose of thinking something through. But how do we know a premise is valid or trustworthy? There is no formula. No single source guarantees reliability. In practice, we work with premises drawn from multiple places:

Assertions by Others – Family members, teachers, journalists, and peers all state things as facts. Some are right. Some are wrong. We judge their credibility case by case.

Expert Opinion – Scientists, historians, doctors, and other specialists often provide starting points for reasoning. But they can disagree. Consensus is not infallibility. Authority is not proof.

Reference Works and Published Information – Dictionaries, textbooks, databases, and handbooks are commonly treated as factual. But they simplify, and they can lag behind updated knowledge.

Personal Experience and Observation – This is often the most persuasive to the individual. What one sees, feels, hears, and remembers forms a strong basis for premises—but also includes bias, limits, and interpretation.

Cultural Assumptions – Premises are sometimes absorbed unconsciously through social norms, media, language, and upbringing. These often go unexamined.

In reality, premises are judged by how well they fit with our current understanding of the world. That understanding itself is shaped by all the sources above—cross-checked, challenged, revised, and sometimes stubbornly held.

There is no algorithm to determine whether a premise is valid. We cannot compute the truth of our assumptions in any final way. What we can do is:

Make premises explicit

Examine where they come from

Test whether they still fit what we know

Stay open to revision when new evidence or better framing appears

This work—identifying, inspecting, and adjusting premises—is the backbone of honest reasoning.

4.2 Making Premises Explicit

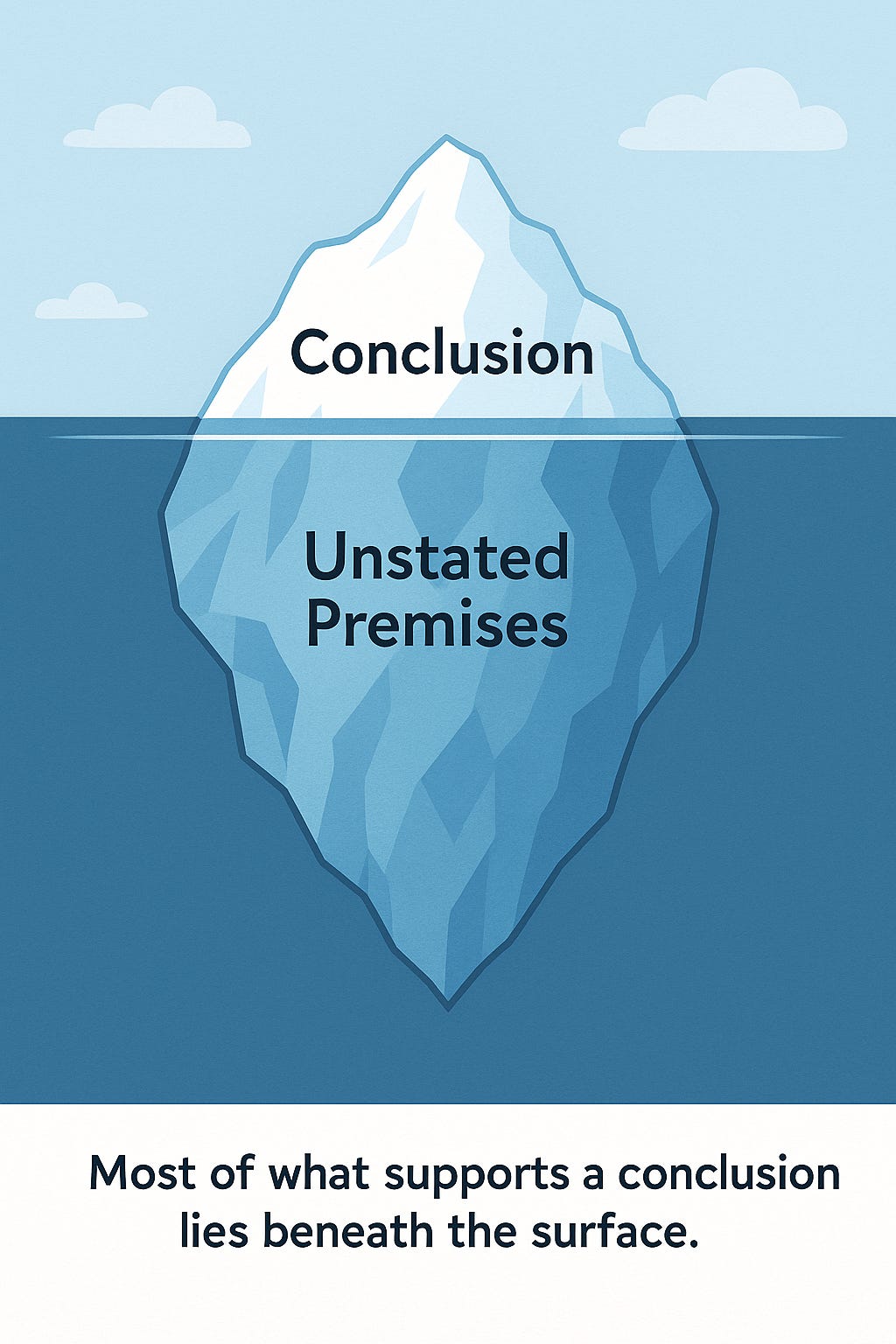

Bringing Hidden Assumptions to the Surface

Most flawed reasoning begins with hidden assumptions. Something is treated as obviously true when it may not be. The first step in improving clarity is to drag these assumptions into the open.

Example 1: “We should intervene because freedom is under threat.”

This relies on multiple hidden premises:

That intervention will protect freedom

That freedom is defined in a particular way

That current trends are a threat

None of these are guaranteed. Unless spelled out, the entire reasoning process depends on what remains unstated.

Example 2: “He’s probably guilty—just look at his face.”

This carries the unstated premise: “People’s faces reveal their guilt.” A highly questionable assumption, yet one that influences real-world judgment.

Example 3: “Let’s invest in this stock. It’s been going up for months.”

The premise here is: “What has gone up will continue going up.” This is a version of momentum bias, not a fact.

Premises often hide in tone, framing, or what seems “obvious.” In discussion, different people may argue past each other, not realizing they disagree on foundational assumptions.

Practical Heuristic:

When evaluating an argument—especially one that feels persuasive—pause and ask:

What would have to be true for this to make sense?

What is being taken for granted but not said?

Clarity begins when assumptions are no longer invisible.

4.3 Testing the Grounding of Premises

Distinguishing Between Supported and Arbitrary Assumptions

Not all premises are equal. Some are supported by experience, evidence, or long-standing practice. Others are little more than slogans, biases, or untested beliefs.

Example 1: “People are basically rational.”

This is a premise in many economic models. But it is not self-evident. Behavioral data suggest people are often inconsistent, emotional, and short-sighted in decision-making. This doesn’t make the premise useless—but it makes it conditional and subject to challenge.

Example 2: “The climate is changing because of human activity.”

This premise is widely accepted in mainstream science, based on accumulated evidence across disciplines. It is contested by some, but the challenge must meet a high evidentiary bar to displace it. Here, the premise has substantial empirical grounding.

Example 3: “Teenagers today are more fragile than past generations.”

This premise floats through opinion columns and public talk. But what is the evidence? Are we measuring fragility? Is it a real trend or a shift in language and norms? This premise may be appealing, but it needs grounding.

A premise may be grounded in:

Observable, repeatable evidence

Historical trends that remain coherent

Direct experience consistently confirmed

Consensus that is accountable to critical review

A premise is weak or arbitrary if:

It rests on vague impressions or clichés

It cannot be tested or defined clearly

It collapses under counterexample

It is maintained only by repetition or emotional appeal

Heuristic for Testing:

Ask: Where does this assumption come from?

Ask: What would it take to disconfirm it?

Ask: Would someone from another field or background question this?

Sound reasoning does not begin with perfect premises. It begins by asking whether they are strong enough to carry the weight of the argument that follows.

4.4 Adjusting Premises Responsively

When to Modify Assumptions in Light of Evidence

Good reasoning is not about being right from the start. It is about being responsive—recognizing when a premise no longer fits the facts or the context and making the needed adjustments.

Example 1: “This business model always works.”

If a strategy that once succeeded begins to fail, the premise must be revised. Maybe the market changed. Maybe consumer behavior shifted. Maybe competition adapted. Sticking to a premise past its expiry date leads to failure.

Example 2: “This student is lazy.”

If new information shows the student has been dealing with illness, caretaking, or systemic obstacles, the premise may need revision. Personal judgments often rest on thin assumptions. When evidence contradicts those, the right move is to rethink.

Example 3: “This medication is safe.”

A widely used drug may be assumed safe based on earlier trials. But if adverse effects begin to appear at scale, the premise must be revisited. The world does not owe consistency to our prior beliefs.

Being willing to revise a premise is not weakness. It is the core of adaptive reasoning. Premises are tools, not truths. Some are provisional. Some must be retired.

Heuristic for Adjustment:

Ask: Has this assumption stopped working?

Ask: Do recent outcomes make more sense under a different premise?

Ask: If I heard someone else clinging to this belief, would I think they were being stubborn?

No premise is sacred. A strong thinker updates the foundation as well as the conclusions.

4.5 Recap: Premises as the Front Line of Reasoning

To reason clearly, one must learn to:

Recognize assumptions instead of gliding over them

Test their grounding instead of trusting their familiarity

Revise them in the face of contrary evidence

This work is not glamorous. It is not dramatic. But it is essential. A flawed premise—left uninspected—leads the entire chain of thought astray. And yet every argument, every explanation, every judgment begins with a premise.

If the premise is faulty, no amount of elegance downstream will fix it.

If the premise is strong, even imperfect reasoning may hold together.

Reasoning begins not with proof, but with clarity about where we are starting.

That is the whole problem: assumptions have been treated as immutable self-evident axioms. They should really be treated as hypothesis, and every evidence should really strenghten or weaken the hypothesis.

To claim axiom over natural phenomenon is to claim absolute knowledge about nature, that is dogma, religion, not science.