Chapter 3: Building Internally Consistent Narratives

From: Reason: Thinking Without Guarantees: A Guide to Some Reasoning Heuristics

For context, see:

Reason: Thinking Without Guarantees: A Guide to Some Reasoning Heuristics

Chapter 1: What Reasoning Is and What It Is Not

Chapter 2: Connecting Reasoning to Direct Observation

3.1 On the variability of the world

There is variability in the world in all things, objects, and events. This is not measured variability necessarily, but the naturally observed variability in the world. More often than not, things appear random, and we try to untangle causes by performing the same actions again, by trying to control factors that could be causing things to happen. In the majority of complex situations, we do not have that luxury.

Some think this is because some things are uncaused—called "random" by some. Others think it is because everything is caused—called "deterministic" by some. Regardless of your theological position on this, the world is highly variable, and we seldom can see the causes in most complex situations.

I throw my lot in with the determinists, since I think the other position is incoherent and inconsistent with the overall regularity of the world.

3.2 Avoiding contradiction in the structure of explanation

An internally consistent explanation does not guarantee that something is true, but an inconsistent explanation cannot be trusted at all. If two claims within a narrative contradict each other—if one implies that something must happen, and the other that it cannot—then the explanation fails to cohere. It may still have parts worth salvaging, but as a whole it is unstable.

Example: Contradictory Medical Claims

Suppose a health commentator argues that fasting improves mental clarity by providing the brain a break from digestion, and in the same discussion insists that the brain depends on constant glucose intake to function optimally. These claims may each sound plausible in isolation, but together they are not consistent. Either the brain needs uninterrupted energy input or it benefits from temporary deprivation—not both, without further clarification.

This kind of contradiction often arises from borrowing claims from multiple domains—e.g., nutritional science, personal experience, cultural beliefs—without reconciling their assumptions.

What Can Be Done:

To check for internal consistency, write down the core steps or claims of the explanation. Look for cases where one claim undermines another. If necessary, add conditions or distinctions (e.g., fasting may help some people under specific conditions) to restore stability. If such adjustments cannot make the claims cohere, then one or more parts must be revised or abandoned.

Key Point: Internal consistency is a minimal requirement for any working explanation. It does not imply correctness, only that the explanation is non-self-defeating.

3.3 Seeking Plausible Causal Stories

Why causal accounts are sometimes more useful than surface associations

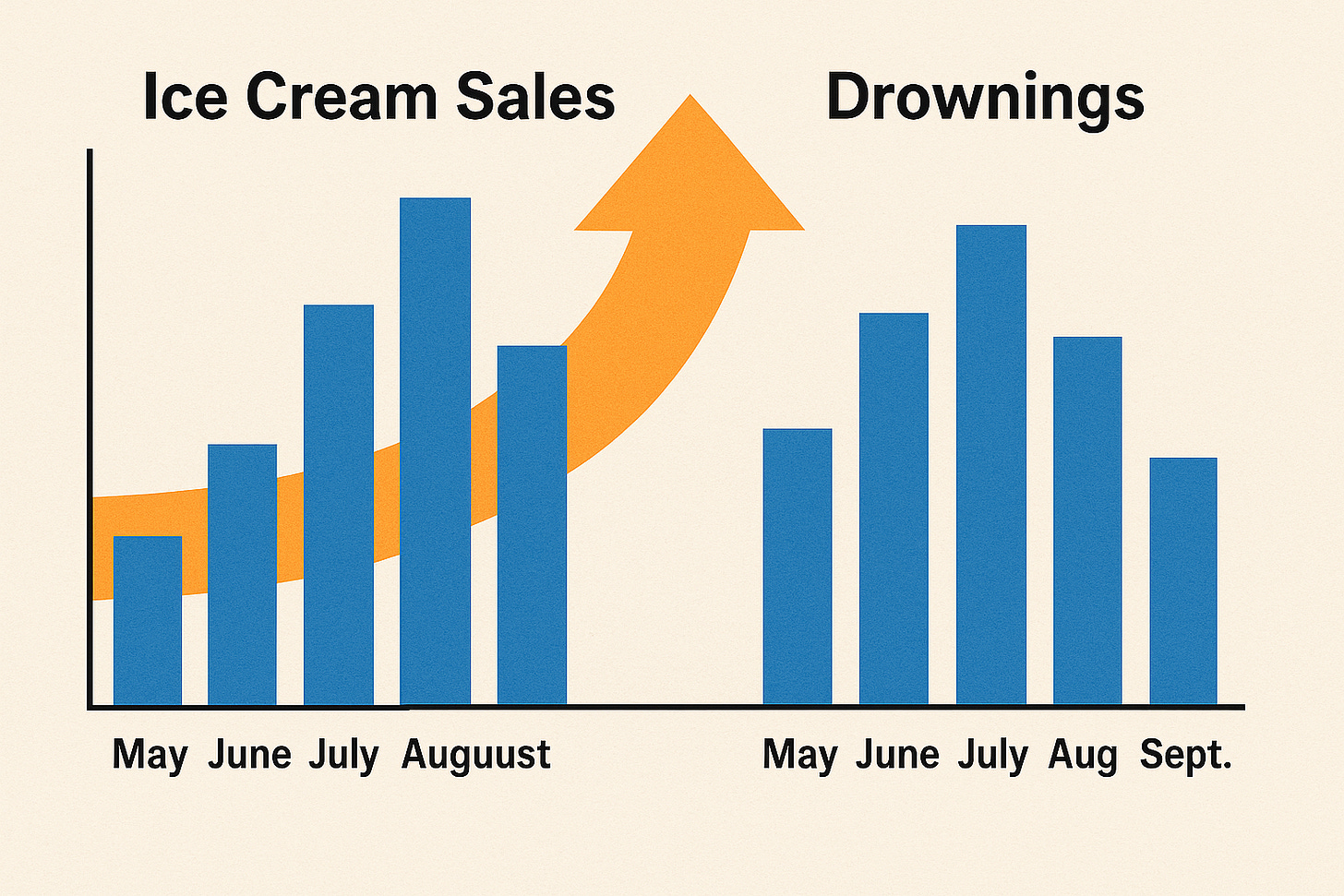

Causality is not something that can be directly seen. It is always inferred. What we observe are sequences: A happens, then B happens. Whether A caused B is a hypothesis, not a fact. People are quick to leap from pattern to cause, but these leaps often fail.

Still, causal explanations are valuable because they attempt to say why something occurs—not just that it occurs.

Example: Behavior Change

Suppose a school implements a new anti-bullying program and sees a drop in reported bullying. One could say the program caused the drop. But that explanation only becomes plausible if other possible influences—new policies, cultural changes, reporting incentives—are ruled out or accounted for. Even then, the causal link is provisional.

Example: Diet and Energy

People often say that cutting sugar “caused” their increased energy. This may be true. Or it may reflect unrelated changes (e.g., better sleep, reduced stress, placebo effects). Causal stories must be tested by comparison, by repetition, and against what is already known to be plausible in biology or behavior. Even then, attribution is uncertain.

Actionable Guideline:

Ask what known processes, mechanisms, or patterns might plausibly link A to B. What would falsify the proposed link? Can any plausible alternative explanation account for the same outcome?

In science, causality is tested through careful design: randomized trials, interventions, long-term tracking. In everyday reasoning, these are often unavailable. That makes causal inference harder—but not impossible. It means causality must always be tentative and grounded in the best-known models of the world, not just personal impression or timing.

3.4 Favoring Explanatory Breadth and Simplicity

Preferring accounts that explain more—but only when warranted

There is value in choosing explanations that account for more than just one thing, but only when those explanations don’t introduce unwarranted complexity or depend on arbitrary assumptions. The idea that an explanation is better because it’s broader or simpler is a rough guideline, not a rule. Many simple explanations are wrong. Some complex ones are right.

Example: Economic Predictions

A theory that tries to explain inflation, unemployment, and wage stagnation using one cause—say, central bank policy—may seem elegant. But if it must ignore supply chains, technological change, consumer psychology, and international trade to maintain that simplicity, then it is probably overreaching.

Example: Alternative Health Claims

A supplement company might claim that their product improves sleep, weight loss, mood, and immune function. That is broad. But the breadth raises suspicion unless a mechanism is specified and supported by replicated evidence. The more effects claimed from one cause, the more scrutiny is needed.

Caution about Simplicity:

Occam’s Razor—favoring simpler explanations—is not a truth-detection device. It is merely a constraint: don't add more parts than needed. But in complex systems, like ecosystems, economies, or minds, simplicity often hides complexity. What seems like a single cause may turn out to be many.

Practical Advice:

If two explanations account for the same evidence, prefer the one with fewer speculative parts.

But if one explanation accounts for more phenomena with modest additional complexity, it may be worth the trade.

Always test against known facts, not elegance.

Final Note on Evidence and Adjudication

In all explanatory reasoning, there is no shortcut past the hard work of judging the quality of evidence. That judgment is unavoidably grounded in:

Prior understanding (what is already known, or believed to be known)

The quality and transparency of the sources

The reproducibility or corroboration of the results

The extent to which the explanation helps make sense of multiple observations at once

Opinions differ on what counts as good evidence. That disagreement cannot be avoided. One must always weigh the evidence against both intuition and understanding, knowing that both are fallible.

In short:

Do not demand absolute proof. It rarely exists.

Do not accept elegant stories at face value. Many are wrong.

Do not reject complexity just because it is messy.

And never confuse explanation with certainty.

Causality is difficult to observe directly and should be treated cautiously.

Plausibility must be judged in light of current understanding, which is always tentative.

Explanatory coherence is not the same as truth, but is necessary for provisional reasoning.

Simplicity (Occam's Razor) is not a rule or proof mechanism, but a tool that sometimes works pragmatically, and often fails.

Evidence must be interrogated, not accepted at face value.

The goal is to reflect the uncertain, complex, and provisional nature of real-world reasoning—not to present an idealized or rationalist account.

Good explanations are provisional, internally stable, causally plausible, and consistent with the best understanding available. That is the best that can be done. And it is often good enough—until it fails.