Reason: Deductive Logic’s Applicability and Limitations

I Return To An Older Theme, A Nerdish One To Be Sure, But Then I’m the Guerrilla Epistemologist And You’re Not

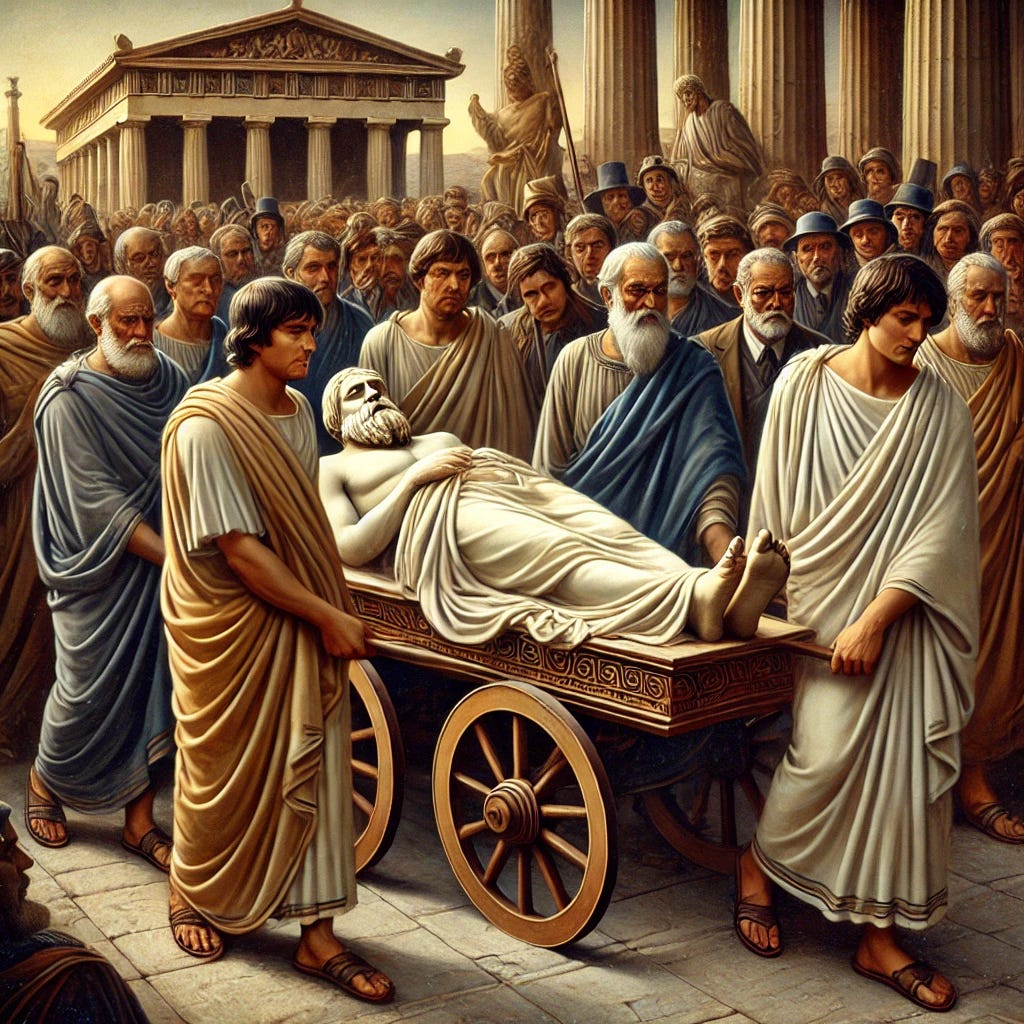

See more on The Funeral of Socrates1

Introduction

Reason is the fundamental human faculty that allows us to make sense of the world, derive conclusions, and navigate reality. Among the various methods of reasoning, deductive logic was held historically as the gold standard for clarity, rigor, and certainty. However, while deductive logic has undeniable strengths, it is far from being a universal tool for reasoning. Its limitations reveal deeper issues about the nature of human thought, the complexity of the world, and the ways in which we form conclusions. This essay explores the nature of deductive logic, its role in reasoning, and its inherent limitations.

Discussion

Deductive Logic: The Ideal of Certain Reasoning

Deductive logic operates on a simple principle: if the premises are true and the reasoning is valid, then the conclusion must also be true. This structure is exemplified by the classic syllogism:

All humans are mortal.

Socrates is a human.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This form of reasoning is truth-preserving—it does not introduce new information but ensures that conclusions necessarily follow from given premises. Deductive logic underlies mathematics, formal proofs, and structured argumentation, making it essential for disciplines that demand precision and rigor.

The Limits of Deductive Logic

While deductive reasoning offers certainty within its formal constraints, its usefulness in real-world reasoning is limited. Several key limitations emerge:

1. Dependence on Premises

Deductive reasoning is only as good as its premises. If the premises are incorrect, the conclusion, though logically valid, is false. For example:

All birds can fly.

Penguins are birds.

Therefore, penguins can fly.

The error here lies in the faulty premise, not the deductive structure. This highlights a fundamental limitation: deduction does not determine truth—it only preserves it. Truth must come from elsewhere, such as observation, experience, or inductive reasoning.

2. Lack of New Knowledge

Deductive reasoning is non-ampliative, meaning it does not expand knowledge—it only makes explicit what is already implicit in the premises. If one only relied on deduction, they could never discover anything new about the world. For example:

If it is raining, the ground is wet.

It is raining.

Therefore, the ground is wet.

This does not tell us anything surprising—it merely restates what was already assumed. Science, exploration, and discovery require ampliative reasoning (such as induction or abduction) that extends beyond what is already known.

3. Limited Applicability to Uncertain or Probabilistic Contexts

Deductive logic functions in an idealized world of absolutes, but reality is full of ambiguity, uncertainty, and probabilistic reasoning. Consider medical diagnosis:

If a person has Disease X, they will test positive.

John tests positive.

Therefore, John has Disease X.

This reasoning assumes certainty, ignoring the possibility of false positives. In many real-world scenarios, probability and uncertainty must be factored in, requiring other forms of reasoning such as rules of thumb rather than strict deduction.

4. The Problem of Infinite Regress

Deductive logic ultimately depends on axioms or foundational premises that are themselves not proven deductively. If every premise required proof, reasoning would fall into an infinite regress, where no conclusion could ever be established. At some point, reasoning must rely on self-evident truths, empirical observations, or pragmatic assumptions.

5. Human Thought Is Not Purely Logical

Human reasoning does not operate as a series of formal syllogisms. Instead, it involves intuition, heuristics, pattern recognition, all placeholders for thinking, for making inferences. Deductive logic is a tool within human reasoning but does not encapsulate how people actually think—a very great mystery. Moreover, deductive logic does not handle meaning, context, or interpretation—these require cognitive flexibility beyond strict logical formalisms.

The Role of Deductive Logic in Reasoning

Deductive logic is a powerful tool but not a universal solution to reasoning. While it provides certainty within a structured system, it is incapable of generating new knowledge, handling uncertainty, or justifying its own premises. In real-world reasoning, deduction must be supplemented with induction, abduction, heuristics, and empirical verification. Human thought is far richer and more complex than formal logic, and a full understanding of reasoning requires moving beyond the limits of deduction.

Validity and Soundness in Deductive Logic

We need to distinguish between the formal notions in deductive logic of validity and soundness, and we're going to talk about each of those in turn. Validity pertains to the formal structure of categorical arguments, and soundness pertains to their applicability to the real world. In a narrow sense, it's truth values, but in a broader sense, it's meaning and relationship to the objective world. To restate, it is necessary to distinguish between two fundamental concepts: validity and soundness. These concepts define the internal consistency and external applicability of deductive reasoning, respectively.

Validity: The Structure of Deductive Logic

Validity pertains only to the formal structure of an argument. An argument is valid if, assuming the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. Validity does not concern itself with whether the premises are actually true—only whether the reasoning follows a logically correct form.

For example:

All cats are reptiles.

Garfield is a cat.

Therefore, Garfield is a reptile.

This argument is formally valid because it adheres to the logical structure of a categorical syllogism. However, it is not a sound argument because the first premise is false.

Soundness: The Relationship to Truth and the Real World

An argument is sound if it is both valid and all its premises are actually true. Soundness goes beyond formal structure and requires an argument to have meaningful, real-world applicability.

For example:

All mammals have a backbone.

Dogs are mammals.

Therefore, dogs have a backbone.

This argument is both valid (its logical structure is correct) and sound (its premises are factually true).

In a narrow sense, soundness pertains to truth values—whether the premises and conclusion correspond to reality. In a broader sense, soundness concerns meaning and how well the argument maps onto the objective world. A formally valid argument may still be meaningless or inapplicable if its premises are irrelevant, based on arbitrary definitions, or disconnected from empirical reality.

This distinction between validity (formal correctness) and soundness (truth and applicability) is crucial in understanding the strengths and limitations of deductive logic. While validity ensures consistency within a system, soundness ensures relevance to the real world—a gap that highlights where deductive logic can fall short.

Qualifying Phrases

All deductive logic needs to be prefaced implicitly with a qualifying phrase, such as “if the following premises are correct, then the conclusion is correct.” We can make this more explicit by re-crafting a syllogism with “If – then” statements which makes it clear the conditional, the tentative nature of the syllogism.

All deductive logic operates within an implicit conditional framework—that is, it assumes the premises are true but does not assert that they are true. This means every deductive argument should, in principle, be prefaced with a qualifying phrase such as:

"If the following premises are correct, then the conclusion necessarily follows."

This implicit conditionality can be made explicit by modifying a standard syllogism. Consider the classic example:

All humans are mortal.

Socrates is a human.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This is traditionally stated as a categorical syllogism, where the premises appear as absolute statements. However, deductive reasoning does not establish the truth of the premises—it merely preserves truth if the premises are true. Making this conditional nature explicit, the syllogism can be restated as:

If all humans are mortal, then this premise holds.

If Socrates is a human, then this premise holds.

If both premises are true, then Socrates must be mortal.

or

If All humans are mortal.

And if Socrates is a human.

Then Socrates is mortal.

These revised forms highlights that deductive logic does not assert truth—it operates conditionally on given premises. The tentative nature of the argument is now explicit, making clear that deductive reasoning itself does not provide new knowledge but only maintains logical consistency within a given framework.

By introducing "if" clauses, we acknowledge that:

The premises may or may not be true.

The conclusion depends on the premises.

Deductive logic preserves truth but does not establish it.

This reformulation is useful because it clarifies the inherent assumptions in deductive logic, making it clear that validity is conditional upon the premises rather than treating them as unquestioned truths.

Cognitive Abilities Vary

Deductive logic consists of valid and invalid forms, including structured syllogisms and common inference rules such as modus ponens and modus tollens. While these logical structures provide a formal basis for reasoning, cognitive abilities vary, and not everyone can grasp these forms.

Common Deductive Forms

Modus Ponens (Affirming the Antecedent)

If it is raining, then the ground is wet.

It is raining.

Therefore, the ground is wet.

This form is generally easy to grasp because it follows a natural conditional pattern.

Modus Tollens (Denying the Consequent)

If it is raining, then the ground is wet.

The ground is not wet.

Therefore, it is not raining.

This form is slightly less intuitive, as it requires thinking in reverse—denying an effect to infer the absence of a cause.

Disjunctive Syllogism (Elimination)

Either the light is on or it is off.

The light is not on.

Therefore, the light is off.

This is generally easy to understand because it presents a binary choice and removes one option.

Hypothetical Syllogism (Chain Reasoning)

If the power is out, then the lights will not work.

If the lights do not work, then we need candles.

Therefore, if the power is out, we need candles.

This form is harder for some people to grasp because it involves chaining multiple conditionals together.

Dilemma (Choosing Between Two Outcomes)

Either we repair the car or we buy a new one.

If we repair it, it will cost a lot.

If we buy a new one, we will have a loan.

Either way, we have an expensive outcome.

This form is harder for some people because it requires balancing multiple conditions and understanding consequences.

Cognitive Variability in Understanding Deductive Forms

Some people will never grasp these forms at all.

Some will grasp them naturally and easily.

Most people will fall somewhere in the middle.

Even among valid forms, some are intuitive, and some require mental effort to process. Similarly, invalid forms—logical fallacies—can be difficult to detect without training.

By sticking to concrete examples rather than abstract letters (A, B, C), we make these logical structures easier to understand without introducing unnecessary symbolic complexity.

Valid and Invalid Syllogistic Forms

Valid Syllogistic Forms

There are 19 valid syllogistic forms in traditional Aristotelian logic, derived from different combinations of major, minor, and middle terms across categorical propositions (e.g., "All X are Y," "Some X are Y," "No X are Y"). These are divided into four figures, depending on the placement of the middle term.

While it is impractical to list all 19, here are some of the most commonly used valid syllogistic forms:

Universal Affirmative (Barbara)

All mammals are warm-blooded.

All dogs are mammals.

Therefore, all dogs are warm-blooded.

Universal Negative (Celarent)

No reptiles are warm-blooded.

All snakes are reptiles.

Therefore, no snakes are warm-blooded.

Particular Affirmative (Darii)

All birds have feathers.

Some animals are birds.

Therefore, some animals have feathers.

Particular Negative (Ferio)

No fish are warm-blooded.

Some pets are fish.

Therefore, some pets are not warm-blooded.

Beyond these, the remaining valid forms are variations involving different distributions of universal and particular statements, but they all maintain logical consistency, ensuring the conclusion follows necessarily if the premises are true.

Invalid Syllogistic Forms (Formal Fallacies)

Invalid forms, or formal fallacies, occur when the conclusion does not logically follow from the premises. There are many more invalid forms than valid ones, as errors in reasoning vastly outnumber correct patterns.

Here are some common invalid syllogistic forms:

Affirming the Consequent (Invalid Conditional Syllogism)

If it is raining, the ground is wet.

The ground is wet.

Therefore, it is raining.

(The ground could be wet for another reason, such as a sprinkler.)

Denying the Antecedent (Another Invalid Conditional Syllogism)

If it is raining, the ground is wet.

It is not raining.

Therefore, the ground is not wet.

(Again, the ground could be wet for other reasons.)

Undistributed Middle (Faulty Connection)

All cats are mammals.

All dogs are mammals.

Therefore, all dogs are cats.

(The shared middle term, “mammals,” does not connect dogs and cats directly.)

Illicit Major (Overgeneralization from a Negative Premise)

No reptiles are mammals.

All dogs are mammals.

Therefore, no dogs are reptiles.

(While this happens to be true in this case, the structure is flawed because it assumes an exclusive relationship that is not logically necessary.)

Illicit Minor (Overgeneralization from an Affirmative Premise)

All fish live in water.

Some pets live in water.

Therefore, some pets are fish.

(Not necessarily true—some pets that live in water might be turtles, amphibians, or other aquatic creatures.)

There are many more formal fallacies, but these illustrate how invalid reasoning often results from incorrect distribution of terms or flawed conditional logic.

Beyond Syllogisms: Other Valid Deductive Forms

1. Modus Ponens (Affirming the Antecedent)

If a car runs out of gas, it will not start.

The car ran out of gas.

Therefore, it will not start.

(A direct application of conditional reasoning.)

2. Modus Tollens (Denying the Consequent)

If a phone battery dies, the phone will not turn on.

The phone turns on.

Therefore, the battery is not dead.

3. Hypothetical Syllogism (Chain Reasoning)

If it snows, the roads will be slippery.

If the roads are slippery, accidents will increase.

Therefore, if it snows, accidents will increase.

4. Disjunctive Syllogism (Either-Or Elimination)

Either the power is on, or the house is dark.

The power is not on.

Therefore, the house is dark.

These valid structures maintain logical integrity and are widely used in mathematics, philosophy, law, and everyday decision-making.

Beyond Syllogisms: Other Formal Fallacies

While invalid syllogistic forms were covered earlier, other formal fallacies extend beyond categorical logic:

1. False Dilemma (Forcing a Binary Choice When More Options Exist)

Either we increase taxes, or the economy will collapse.

(This assumes there are no alternative policies that could prevent collapse.)

2. Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning)

Ghosts exist because many people have seen ghosts.

(The premise assumes the truth of the conclusion.)

3. Equivocation (Shifting Meaning of a Word Mid-Argument)

A feather is light.

What is light cannot be dark.

Therefore, a feather cannot be dark.

(The word “light” changes meaning—from weight to color.)

4. Composition Fallacy (Assuming What is True of Parts is True of the Whole)

Each brick in this building is light.

Therefore, the entire building is light.

(The sum of light parts does not necessarily make a light whole.)

5. Division Fallacy (Opposite of Composition Fallacy)

This cake is delicious.

Therefore, each ingredient in the cake must be delicious.

(Not necessarily—flour and baking soda are not tasty by themselves.)

Summary

There are 19 valid syllogistic forms used in categorical logic.

There are countless invalid forms—errors vastly outnumber correct patterns.

Beyond syllogisms, valid deductive rules include modus ponens, modus tollens, hypothetical syllogism, and disjunctive syllogism.

Beyond syllogisms, formal fallacies include false dilemma, equivocation, circular reasoning, and compositional errors.

These structures define how deductive logic works and where it fails. Many people struggle with valid forms, while others accept invalid reasoning without recognizing the flaws. Clear, concrete examples help make these distinctions more understandable.

A Formal System With Only Narrow Applicability

In the end, it's a formal system that's only narrowly applicable. Its correctness depends upon soundness, which lies outside of the system. And soundness should not be narrowly construed as just true or false. True or false depend upon meaning and objective truth, so soundness clearly is beyond true or false, that is only a very narrow sense of what the word entails.

The deductive system is hard to understand and hard to learn. There's a lot of rules, a lot of forms. Many are quite opaque. Even when given concrete examples, it's still hard to follow. Some are very, very hard to follow as to why they're valid or invalid. Probably as hard as many branches of other types of mathematics. And they don't deal with probabilities at all. That requires more advanced forms of logic which attempt to do so with some success, but partial success.

To restate, deductive logic is a formal system with only narrow applicability. It operates within a closed structure, ensuring that if premises are correct and reasoning is valid, then conclusions must follow. However, its correctness ultimately depends on soundness, which exists outside of the system itself.

Soundness Extends Beyond Truth and Falsehood

Soundness is often framed in terms of truth values, but this is an oversimplification. Truth and falsehood themselves depend on meaning and objective reality, not merely on internal logical consistency. Soundness is a broader concept that concerns how well a logical argument maps onto reality, not just whether it meets formal conditions.

Thus:

Validity ensures the structure of reasoning is correct.

Soundness ensures the argument applies meaningfully to the real world.

Truth and falsehood depend on interpretation, external verification, and empirical or conceptual grounding.

Deductive Logic is Hard to Learn and Apply

Deductive logic is not intuitive for most people. It requires:

Mastery of numerous rules and forms, some of which are complex and unintuitive.

The ability to track abstract structures of reasoning, which can be opaque.

An understanding of validity vs. invalidity, which is often non-obvious.

Even with concrete examples, many logical forms remain difficult to follow. Some are as challenging as advanced mathematics, requiring careful step-by-step analysis to grasp why they are valid or invalid.

Deductive Logic Does Not Handle Probability

Deductive reasoning does not deal with uncertainty. It works in absolute terms:

A statement is either true or false (within the logical framework).

Premises are either correct or incorrect—there is no room for degrees of likelihood.

To handle probability, more advanced forms of logic have been developed, such as:

Bayesian reasoning, which assigns probabilities to beliefs.

Fuzzy logic, which allows for degrees of truth rather than binary true/false values.

Modal logic, which explores necessity and possibility.

These advanced logics attempt to incorporate probability and uncertainty, but only with partial success. The real world is often too complex, ambiguous, and context-dependent for formal logic to fully capture.

Wrapping Up

Deductive logic, while rigorous and precise, is narrow in scope and difficult to master. Its reliance on external soundness makes it insufficient on its own for understanding reality, and it lacks the ability to handle uncertainty and probabilistic reasoning. More advanced logics provide partial solutions, but no formal system fully captures the complexities of real-world reasoning.

The Existential Fallacy (A Difficult Formal Fallacy to Grasp)

The Existential Fallacy is a formal fallacy that is particularly difficult for most people to understand because it involves an implicit assumption about existence that is not justified by the premises.

Example

All unicorns have horns.

Some unicorns are white.

Therefore, some white creatures have horns.

At first glance, this might seem perfectly logical—after all, if all unicorns have horns and some unicorns are white, it follows that some white things have horns, right?

Why This is a Fallacy

The problem is that there is no premise that establishes that unicorns exist in the first place. In classical logic, a universal statement ("All X are Y") does not imply the existence of X. The argument assumes that because "all unicorns" have a property, there must be at least one unicorn to apply that property to—but that assumption is invalid.

Why This is Hard to Understand

It feels intuitive. People naturally assume that if we talk about a category, at least one member of that category must exist.

It requires an understanding of implicit assumptions. The fallacy occurs not because of explicit contradictions but because of an unwarranted leap from a universal statement to an existential conclusion.

It seems structurally similar to valid arguments. Many valid syllogisms look just like this one, but they work because their subjects actually exist.

Another Example Using a More Familiar Context

All Martians have three arms.

Some Martians are green.

Therefore, some green creatures have three arms.

The problem remains the same—the premises do not establish that Martians exist. If Martians don't exist, then we cannot conclude that any green creatures (or any creatures at all) have three arms.

Key Takeaway

The Existential Fallacy is difficult for most people to grasp because it exploits a subtle, hidden assumption—that talking about a category (like unicorns or Martians) implies that something in that category must exist. This is not the case in formal logic, which distinguishes between universal claims and existential claims.

Summary

Deductive logic is a formal system with narrow applicability, ensuring that if premises are valid, conclusions necessarily follow. However, its correctness depends on soundness, which lies outside the system and should not be narrowly construed as mere truth or falsehood—soundness relates to meaning and objective reality. Deductive logic is also difficult to learn, as it requires mastering numerous rules and forms, some of which are highly opaque. Even with concrete examples, many forms remain hard to follow, and certain fallacies, such as the Existential Fallacy, demonstrate how subtle errors in reasoning can be difficult to detect.

Furthermore, deductive logic does not handle probabilities, as it is strictly deterministic. More advanced forms of logic, such as Bayesian reasoning, fuzzy logic, and modal logic, attempt to incorporate uncertainty with partial success. This limitation highlights that deductive logic alone is insufficient for understanding real-world reasoning, which often involves ambiguity, likelihoods, and interpretation.

The Story of Socrates and the Hemlock

The story of Socrates' death by hemlock is one of the most famous moments in the history of philosophy, immortalized primarily in Plato’s dialogues, especially Phaedo, Apology, and Crito. Whether every detail of the account is historically accurate is uncertain, but the overall story is widely accepted.

The Trial and Conviction

In 399 BCE, Socrates was put on trial in Athens, charged with:

Corrupting the youth—he encouraged young Athenians to question authority, tradition, and accepted wisdom.

Impiety—he was accused of not believing in the gods of the city and introducing new deities (possibly referring to his mention of a divine inner voice or "daemonion").

The trial was public, and Socrates, in his defense (Apology), refused to grovel or beg for mercy. He famously insulted the jury, suggesting that instead of punishing him, they should reward him with free meals for his service to Athens. Unsurprisingly, he was found guilty by a narrow margin.

For sentencing, he was given the option to propose his own punishment. His followers suggested exile or a fine, but Socrates mockingly suggested he should be treated as a hero. This irritated the jury, and a larger majority voted for his execution—a death sentence by drinking hemlock, a lethal poison.

The Last Days in Prison

Socrates spent his final days in prison, surrounded by friends and students, including Plato, Crito, and Phaedo. He continued discussing philosophy until the very end, talking about the immortality of the soul and how death should not be feared.

Crito, one of his wealthy followers, offered to bribe the guards to allow Socrates to escape. Socrates refused, arguing that one must obey the laws of the city, even if they are unjust. He believed fleeing would betray his lifelong commitment to ethical principles.

The Hemlock and Death

When the time came, a jailer brought Socrates a cup of hemlock, a poisonous plant that paralyzes the body and eventually stops the heart. Before drinking, he offered a final lesson, calmly discussing how the soul is freed from the body at death.

At the time of Socrates (5th century BCE, Classical Athens), the body of the deceased was typically exposed on a bier rather than placed in a closed casket. The funeral customs of ancient Athens followed a structured three-stage process:

1. Prothesis (Laying Out the Body)

The deceased was washed, anointed with oil, and dressed (often in white garments).

The body was placed on a bier in the home and covered with a cloth, leaving the face exposed.

Relatives and friends mourned, sang dirges, and paid their respects.

Women of the family, particularly close female relatives, played a key role in mourning.

The body was displayed for one or two days to allow people to say their goodbyes.

2. Ekphora (Funeral Procession)

The body was carried in a formal procession to its burial site.

This often took place before dawn.

Professional mourners might be hired to lament and wail.

The bier was sometimes carried on a cart or carried by pallbearers.

3. Burial or Cremation

The body was either buried or cremated, depending on family traditions and beliefs.

Inhumation (burial) was common in early Greece, but by Socrates' time, cremation had become widespread, especially among the elite.

Cremated remains were placed in an urn and buried.

Grave markers (stele) were often erected, depicting the deceased in life.

Offerings and Post-Funeral Rites

Offerings of food, oil, and libations were made at the grave.

Families continued to visit the graves of their ancestors and performed annual rites.

It was believed that honoring the dead properly ensured their peace in the afterlife.

Cultural and Philosophical Views

Socrates himself, as recorded in Plato’s dialogues, displayed indifference to his own death and burial, famously saying in the Phaedo:

"You may bury me if you can catch me."

This reflected his belief that the soul was separate from the body, and once dead, the body was of little importance.

Thus, at the time of Socrates, bodies were typically laid out on a bier before burial or cremation, rather than hidden in a closed casket.