Understanding the World: Stupid Wetware Tricks

I once again try to get a handle on the fundamental operations of the human brain, nervous system, and associated systems.

Introduction

The human organism, our "wetware," encompasses the entire biological system that enables life: the brain, nervous system, sensory organs, motor functions, and internal regulation. It is through this system that we sense, think, act, communicate, and maintain equilibrium. However, any attempt to define or categorize the fundamental operations of this wetware quickly becomes entangled in the limitations of language, conceptual frameworks, and the recursive nature of studying the mind with the mind itself.

From sensing and perceiving to categorizing, generalizing, abstracting, and expressing thoughts through language, the human organism operates within a web of interconnected processes. Yet the task of identifying "fundamental" mental operations is elusive—what qualifies as fundamental depends on how these operations are defined, and the definitions themselves often highlight the imprecision of language. This essay revisits these questions, from previous year’s essays on Substack, to offer an exploration of the wetware's capabilities, its underlying processes, and the challenges of describing them comprehensively.

Discussion

The Core Capabilities of the Human Organism

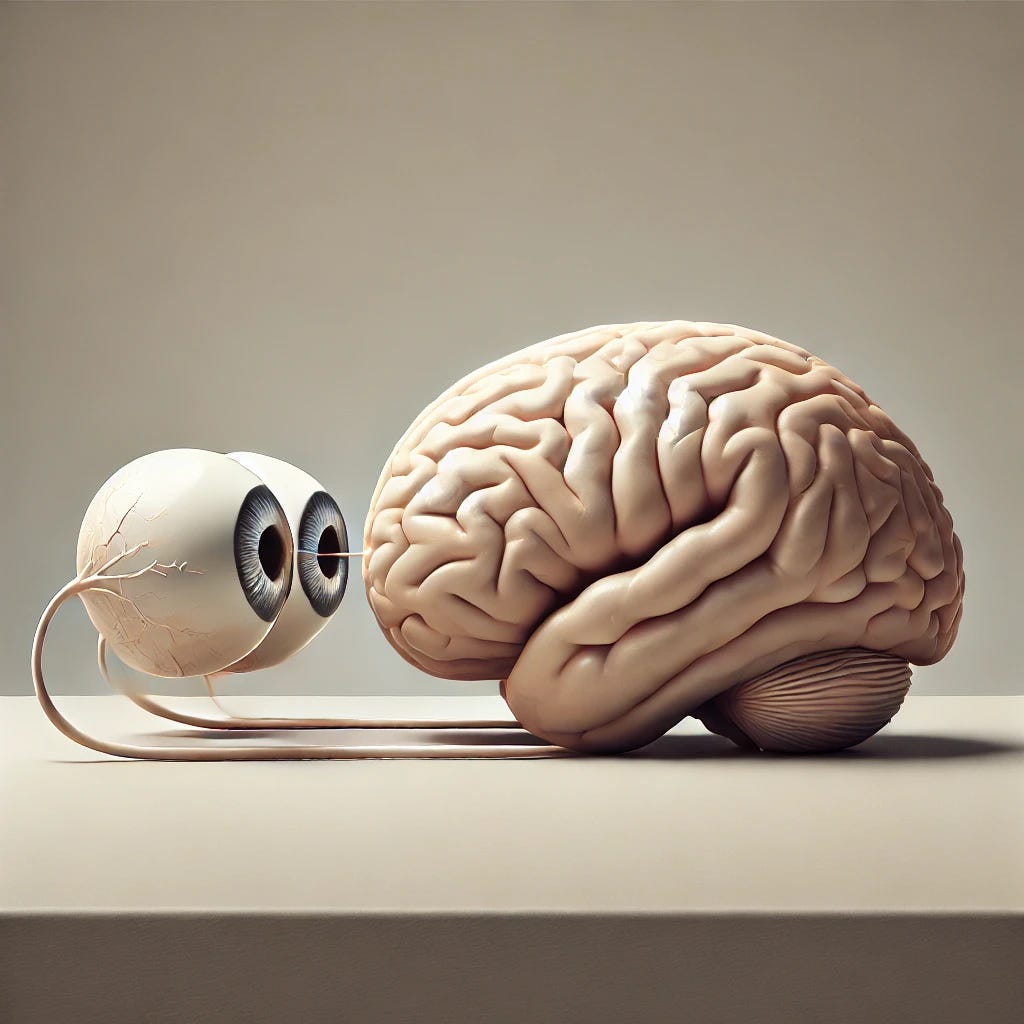

Sensing and Perceiving the World

Our interaction with the external world begins with sensory input—our ability to detect and interpret stimuli through sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. But perception goes beyond raw data collection. It involves filtering, integrating, and constructing coherent representations of the world, bounded by the limitations of our sensory systems and our limited existence within human-scaled time and space.Example: A rainbow appears to us as a multicolored arc, yet it is merely the result of light refracting through water droplets. Our perception simplifies the underlying physics into an accessible sensory experience.

Challenge: While we recognize patterns in sensory input (e.g., the familiar shape of a face), this recognition is prone to errors like pareidolia, where we "see" faces in inanimate objects such as a tree knot or a cloud.

Moving and Acting on the World

Movement enables us to interact with our environment, whether through simple reflexes or complex, intentional actions. This capability stems from an understanding of causality—how actions lead to changes in the world.Example: When you reach for a cup of coffee, your brain calculates the trajectory, adjusts for the cup’s weight, and balances your posture, all while you consciously focus on drinking. These movements integrate reflexive and deliberate processes.

Contrast: Reflexive actions, such as jerking your hand away from a hot stove, are automatic and bypass conscious thought.

Internal Awareness and the Interplay of Emotion and Cognition

Internal awareness—our capacity to think, feel, and experience—arises from the deep interconnection of emotion and cognition. Far from being separate, these systems influence and depend on one another.Example: Anxiety before a public speech involves both emotion (fear) and cognition (anticipation of potential outcomes). Emotional states affect reasoning, just as reasoning can shape emotional responses. Not every state can be expressed in words - many of too subtle.

The Mystery of Thought: Consciousness, the experience of "being aware," remains one of the most profound mysteries of wetware. How does a biological system produce subjective experience? While we can describe awareness in terms of brain processes, its essence eludes precise definition.

Language as Expression, Not Thought

Language is not thought itself but a tool for encoding and expressing it. It allows us to articulate abstract ideas, share knowledge, and connect with others, but it is inherently limited by its structure and precision.Example: Words like "love" or "freedom" attempt to capture complex, multifaceted experiences but fall short of encompassing their full depth.

Imprecision: Abstraction and generalization are central to language, but these processes often obscure nuance. For instance, the term "abstraction" can refer to simplifying a visual image, distilling a philosophical idea, or generalizing a concept—all different phenomena grouped under one word.

Social Role: Beyond expressing thoughts, language facilitates cooperation. A simple instruction like "pass me the salt" relies on shared understanding, context, and the capacity to interpret intention beyond the literal meaning of words.

Maintaining Homeostasis

The wetware operates as a self-regulating system, maintaining internal stability through complex networks of chemical, neurological, and electrical processes.Example: After vigorous exercise, the body releases hormones to regulate blood sugar and prompts sweating to cool down, maintaining equilibrium in response to external stressors.

Integration of Systems: Homeostasis depends on constant communication between the brain, hormones, and organs. For instance, the hypothalamus monitors body temperature and initiates physiological adjustments when deviations occur.

The Challenge of Defining Fundamental Operations

Multiplicity of Frameworks

Attempts to enumerate fundamental operations often lead to competing claims about what qualifies as "core" processes.Pattern Recognition: Some argue that pattern recognition underlies all cognition, from recognizing faces to identifying abstract relationships.

Abstraction: Others suggest that abstraction—the ability to generalize from specific instances—is more fundamental.

Generalization and Specificity: Another perspective emphasizes the interplay between generalization (finding commonalities) and its inverse, specificity (applying general principles to particular cases).

Example: Is recognizing a face (pattern recognition) distinct from abstracting the idea of "friendship" based on interactions with multiple people? These processes overlap, challenging efforts to isolate them.

Theoretical and Practical Challenges

While it may be theoretically possible to catalog all mental operations—using AI trained on dictionaries, for example—the endeavor is constrained by the limitations of language and the immense variability of human cognition.Example: Earlier attempts by the author using AI have generated lists of hundreds of potential operations, from sorting to categorizing to problem-solving. However, these lists often highlight the redundancy and overlap inherent in our conceptual frameworks. Attempts to organize them with dependencies, subclass them, network them, failed.

The Limits of Language and Understanding

Language, while powerful, is imprecise and often fails to capture the nuances of mental and biological processes. Categories and definitions serve as useful tools but lack inherent meaning.Example: The word "thought" encompasses a vast range of phenomena, from fleeting impressions to deliberate reasoning. Efforts to define "fundamental" mental operations inevitably reflect the limitations of the very language used to describe them.

Summary

The human organism—its "wetware"—is an extraordinary, interconnected system that enables sensing, acting, feeling, thinking, and maintaining equilibrium. While efforts to define fundamental operations highlight key processes like pattern recognition, abstraction, and homeostasis, they also reveal the limitations of language and conceptual frameworks. Language, though essential for communication and thought, is imprecise and often inadequate for capturing the full complexity of these phenomena.

Ultimately, our attempts to understand wetware reflect both the power and the limitations of the human mind. The recursive challenge of studying cognition with cognition itself ensures that any descriptions we create are provisional at best. Yet, even in their imperfection, these efforts illuminate the intricate and remarkable nature of the human organism.

Suggested Readings

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Edelman, G. M. (1992). Bright air, brilliant fire: On the matter of the mind. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Pinker, S. (1997). How the mind works. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.