The Dual Nature of Grudges: Evolutionary Adaptation and Psychological Implications

An Examination of Enmity, Pathology, and Reconciliation in Human Behavior

Note: Again, using ChatGPT to find sources and wordsmith around my observations.

Author’s Preface

My wife often maintains that I hold too many grudges and keep them for too long. Me? —A kind and gentle soul without a vindictive bone in his body, someone who would give you the shirt off his back and only charge a nominal fee. It just can't be!

In any case, I decided to consult doctor ChatGPT. Can't be worse than dealing with any other quack.

Oh yeah, I am very familiar with the writings of Jane Goodall, Frans deWaal and many others on primate behaviour.

Introduction:

Grudges, defined as persistent feelings of ill will or resentment resulting from past injuries or offenses, are a common aspect of human experience. While often viewed negatively, grudges may serve adaptive functions, aiding in the recognition and avoidance of potential threats. This essay explores the evolutionary underpinnings of grudges, their psychological manifestations, and the role of reconciliation, drawing on empirical research and theoretical perspectives.

Discussion:

Enmity: The Adaptive Function of Grudges

From an evolutionary standpoint, holding grudges could have conferred survival advantages by promoting caution toward individuals who previously caused harm. This vigilance would help individuals avoid future threats, thereby enhancing survival and reproductive success. Research in evolutionary psychology suggests that emotions like resentment may have evolved to signal social boundaries and deter exploitation (Buss, 2000).

Emotional vs. Cognitive Components of Grudges

Grudges encompass both emotional and cognitive elements. Emotionally, they involve feelings of anger or resentment; cognitively, they include the memory of the offense and the offender. While these components are interconnected, they can function independently. For instance, one might remember an offense without harboring strong emotions, or feel resentment without recalling specific details. Neuroscientific studies indicate that different brain regions are involved in processing emotional and cognitive aspects of grudges, suggesting a complex interplay between these components (Decety & Jackson, 2004).

Grudge Persistence and Evolutionary Purpose

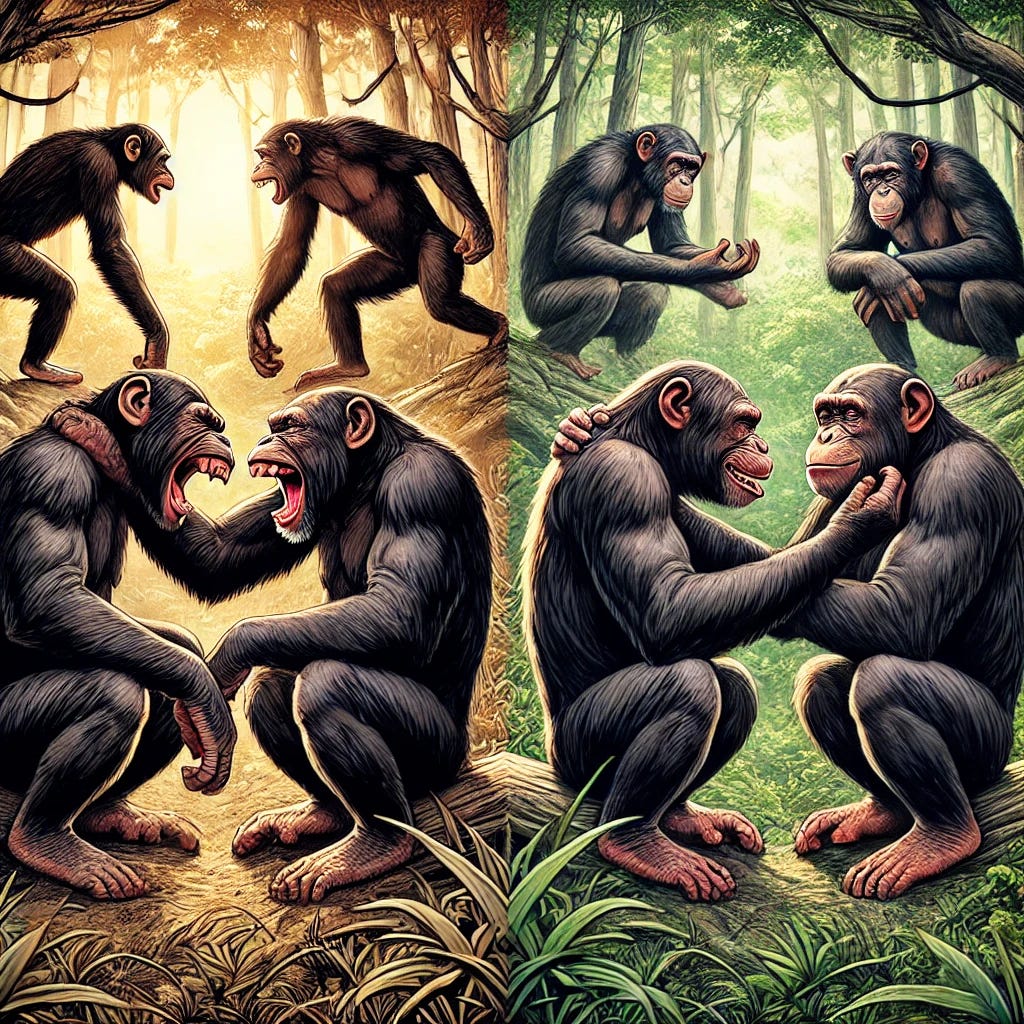

The persistence of grudges may be linked to their evolutionary role in social regulation. By maintaining a memory of past transgressions, individuals can navigate social hierarchies and relationships more effectively. This behavior is observed in non-human primates; for example, chimpanzees remember past conflicts and adjust their interactions accordingly (de Waal, 1989). Such mechanisms likely evolved to promote social cohesion and deter repeated offenses.

Pathology: When Grudges Become Maladaptive

Grudges and Pathological Aggression

While grudges can serve adaptive functions, they may become maladaptive when they lead to excessive or prolonged aggression. In extreme cases, individuals may develop fixations on perceived injustices, resulting in behaviors such as stalking or violence. Psychological research has linked such pathological grudge-holding to personality disorders, including narcissistic and borderline personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Sadistic Enjoyment and Guilty Pleasures

Some individuals derive pleasure from fantasies of revenge or witnessing others' suffering, a phenomenon known as schadenfreude. While common, these feelings can become problematic when they dominate one's thoughts or lead to harmful actions. Studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of trait aggression are more prone to experiencing schadenfreude, indicating a potential link between underlying aggressive tendencies and the enjoyment of others' misfortunes (James et al., 2014).

Cultural Sanctioning of Atrocities

Throughout history, societies have sanctioned violence against perceived enemies, often framing such actions as justified retribution. This cultural endorsement can normalize extreme behaviors, leading to atrocities such as genocide or torture. Social psychological research highlights how group dynamics and authority figures can influence individuals to commit acts they might otherwise find reprehensible (Milgram, 1963).

Reconciliation: Moving Beyond Grudges

Letting Go of Enmity

The adage "let bygones be bygones" reflects the human capacity for forgiveness and the desire to move past conflicts. Forgiveness has been associated with numerous psychological benefits, including reduced stress and improved mental health (Worthington & Scherer, 2004). However, the decision to forgive is complex and influenced by factors such as the severity of the offense and the offender's remorse.

Reconciliation in Animal and Human Behavior

Observations of non-human primates, such as chimpanzees, reveal behaviors akin to human reconciliation. After conflicts, chimpanzees often engage in affiliative behaviors like grooming to restore social bonds (de Waal, 1989). These behaviors suggest that reconciliation mechanisms are deeply rooted in our evolutionary history. In humans, reconciliation processes are more complex, involving verbal communication and cultural norms, but serve similar functions in maintaining social harmony.

Friendship and Social Bonds Amidst Grudges

Despite the potential for grudges to disrupt relationships, strong social bonds often persist. Friendships and familial ties can withstand conflicts through effective communication and mutual understanding. Research indicates that individuals with secure attachment styles are more likely to engage in constructive conflict resolution and less likely to hold grudges (Burnette et al., 2009).

Summary:

Grudges are multifaceted phenomena with both adaptive and maladaptive aspects. Evolutionarily, they may have served to protect individuals from repeated harm by promoting caution. However, when grudges become entrenched, they can lead to pathological behaviors and hinder reconciliation. Understanding the balance between enmity, pathology, and reconciliation is crucial for fostering healthier interpersonal relationships and social cohesion.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-14907-000

Burnette, J. L., Davis, D. E., Green, J. D., Worthington, E. L., & Bradfield, E. (2009). Insecure attachment and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of rumination, empathy, and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(3), 276-280. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-00498-006

Buss, D. M. (2000). The dangerous passion: Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. New York, NY: Free Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-07205-000

Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2004). The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 3(2), 71-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582304267187 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15537986/

de Waal, F. B. M. (1989). Peacemaking among primates. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674659216

Other Readings:

POLYGLOTWORKS. (2024, October 2). The dark side of human nature: Understanding the psychology of taking revenge and holding grudges. Retrieved from https://www.polyglotworks.com

Museum of Science. (2023, November 14). Jane Goodall on what we can learn from chimpanzees. Retrieved from https://www.mos.org

Verywell Mind. (2023, November 5). How holding a grudge can hurt you. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com

Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest. (2023, February 12). Conflict and reconciliation. Retrieved from https://chimpsnw.org

Psych Central. (2022, October 16). The psychology behind grudges (and those who hold them). Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com

Live Science. (2022, August 16). The evolution of human aggression. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com

Nature. (2022, August 8). Bonobo apes pout and throw tantrums — and gain sympathy. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com

Barber, N. (2022, March 9). Bearing a grudge: Why hostility gets frozen in place. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com

The Swaddle. (2022, March 4). Why holding grudges can be emotionally satisfying. Retrieved from https://theswaddle.com

Psychology Today. (2021, February 28). For the love of the grudge: Why we can't forgive or forget. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com

Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest. (2014, September 12). Conflict and reconciliation. Retrieved from https://chimpsnw.org

Psychology Today. (2014, April 18). Grudge: Holding one. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com

Association for Psychological Science. (2011, October 3). The complicated psychology of revenge. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org

Springer. (2009, September 22). The function and determinants of reconciliation. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com

Greater Good. (2008, February 29). The forgiveness instinct. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu

Springer. (2006, October 25). Conflict resolution in chimpanzees and the valuable-relationships hypothesis. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com

Springer. (2006, October 12). Managing conflict: Evidence from wild and captive primates. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com

Psychology Today. Injustice collecting. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com

Psychology Today. For the love of the grudge: Why we can't forgive or forget. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com

JSTOR. Reconciliation and consolation among chimpanzees. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org

Emory University. Reconciliation in captive chimpanzees: A reevaluation with controlled observations. Retrieved from https://www.emory.edu