Reason: Universal Causality, Bounded Analysis, and the Rarity of Regularities

An inductive account of determinism, probability, and the map–territory gap

Author’s Preface

This essay gathers together a set of postulates about how the world works and how we describe it. The main claim is simple: all events have causes. This position is defended not as dogma but by induction, based on repeated experience of the world. Still, causality is often too tangled for us to follow clearly. What we usually call “laws” or “probabilities” are not universal truths but patterns that show up only in limited, controlled conditions. Randomness does not mean “without a cause,” but rather “too complex for us to understand at present.”

The essay begins with axioms about inner and outer worlds, emphasizes causality as a foundation, and explains why boundaries and controls are needed to find regularities. It then considers probability as a mathematical tool, not a window into acausality, and finishes with a caution: our models are maps, not the territory itself.

Introduction

The starting point is axiomatic. There is an outer world that exists independently of us, and an inner world through which all experience is filtered. To deny the outer world is self-defeating, since denial itself presupposes a world in which that denial takes place. Survival depends on interacting with the outer world, and interaction presupposes causality.

Causality is real, but it is also tangled. We rarely see the whole chain of causes. Instead, we make sense of fragments. Language—both natural and mathematical—helps us describe these fragments. But language is approximate, often ambiguous, and always abstract. Mathematics allows counting and measurement once objects and boundaries are fixed, but it too is only a way of describing, never the thing itself.

From this perspective, determinism is not a dogmatic claim but an inductive one. Repeatedly, acting in the world succeeds because similar causes produce similar effects. Where causes are unclear, events may appear random. But randomness is better understood as a placeholder for ignorance than as evidence of acausality.

Discussion

Begin with axioms for reasoning about experience and reality:

There is an inner world and an outer world.

The outer world exists; denying it is self-defeating.

Survival depends on manipulating the outer world, sometimes successfully, often not.

Causality is real and can be used to act effectively, unlike Hume’s skeptical reading of “constant conjunction.”

Causality is complex and entangled; only parts are ever grasped, sometimes enough for survival.

The inner world is the ground of awareness; nothing about the outer world is known except through it.

The inner world depends causally on the body and thus on the outer world.

Language is not identical with thought, but in humans it is tightly bound to thought and communication.

The “thing in itself” is unknowable; knowledge concerns abstractions of it.

Words are ambiguous, fuzzy, and often metaphorical; even so, they suffice for effective action.

From these axioms follows a working stance. The world is objective and causally structured. Arguments against determinism risk self-defeat because reasoning itself relies on stable connections between evidence and conclusion. Yet causality is deeply entangled. Numerical and qualitative factors are innumerable; only some predominate within a bounded context. Gaining traction requires drawing boundaries, naming objects, and fixing conditions so that causes can be investigated.

Determinism by Induction

Inductive justification: Regular success in everyday life and in experiment shows that repeatable links exist between causes and effects.

Randomness as ignorance: What we call “random” marks the limits of our knowledge. When controls and instruments improve, causes that were once hidden can sometimes be revealed.

Self-defeat of anti-determinism: Arguments that deny determinism use reasoning, evidence, and logic, which themselves presuppose stable causal order.

Entanglement, Predominance, and the Necessity of Boundaries

Causal entanglement: The number of contributing factors to any event is vast and often beyond comprehension.

Predominance: Despite the complexity, some factors dominate in a given situation. Prediction depends on identifying these dominant factors and fixing background conditions.

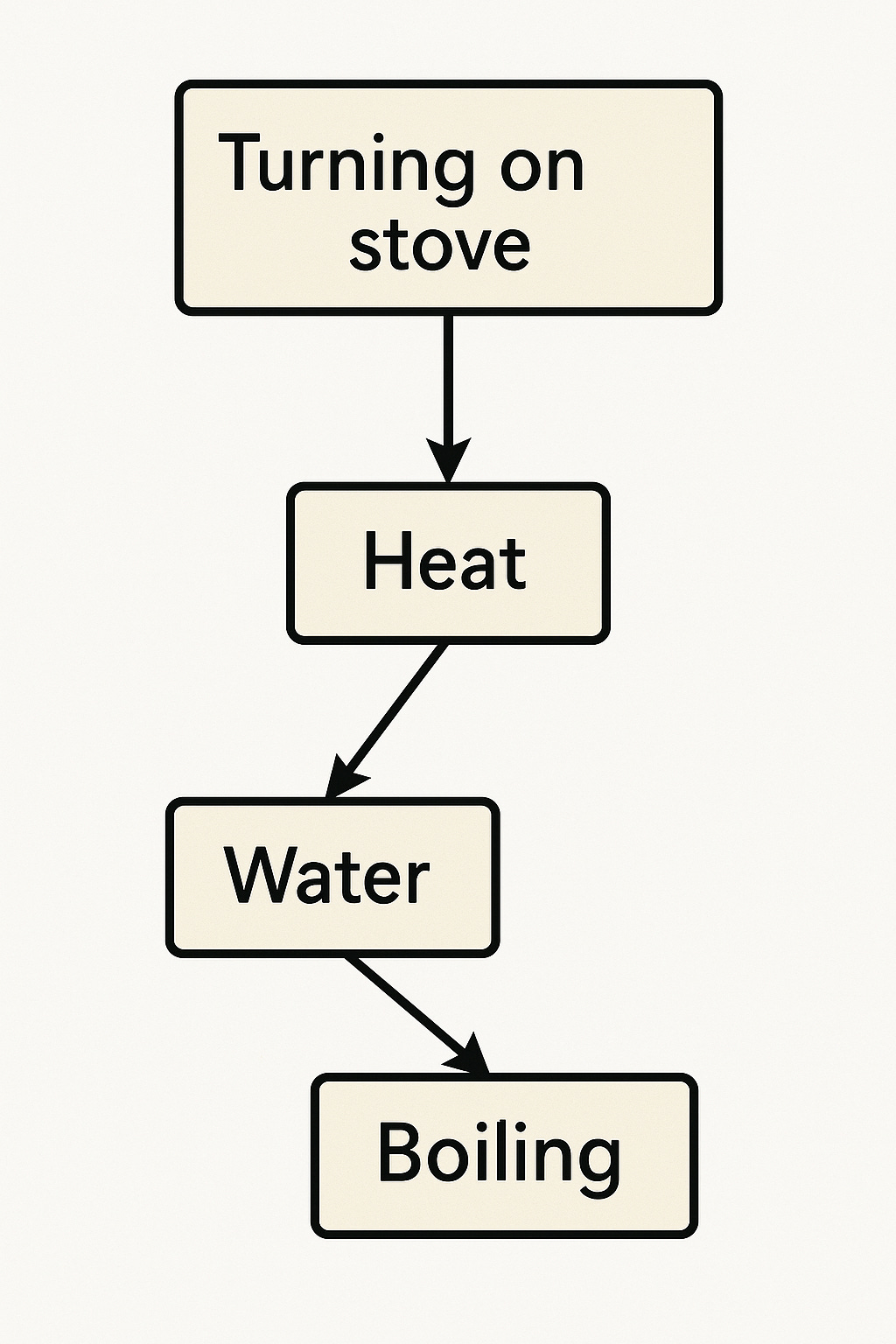

Bounded situations (states): We can only analyze events by drawing boundaries—identifying an initial condition (State A) and a subsequent outcome (State B). Between A and B, causal chains operate. Within and beyond these boundaries, complexity expands without limit.

Stabilization: Experimental design or everyday “life controls” suppress interference, making causal structure more visible.

Regularities Are Rare—and Often Manufactured

Rarity: Regularities do not appear everywhere. Most of the time, causal entanglement prevents simple, lawlike patterns.

Created order: Regularities often show up only when we impose controls—scientists, engineers, or even ordinary people stabilize conditions so that order can emerge. Some philosophers call these “nomological machines,” though the term adds little beyond the idea of bounded, controlled situations.

Against acausality: To say some events are uncaused makes no sense. Even statistical patterns presuppose some underlying generator. Can something be uncaused but still show statistical regularity? Is it just a mystery, or incoherent?

Probability as a Tractable Summary

From variability to distribution: Even in deterministic systems, small uncontrolled differences lead to variability. When stabilized conditions yield a consistent long-run pattern, a probability distribution can summarize it.

Aggregate use: Probabilities work well for predicting aggregates and frequencies in the long run.

Individual limits: Probabilities do not predict single cases in complex domains. Individual events are too affected by hidden or uncontrolled factors.

Propensities: The term “propensity” is sometimes used to describe causal tendencies that underlie probabilities. It is useful only when tied to concrete, testable situations. It may just be a fancy way of saying there are complex caused that yield statistical regularity.

Quantum Puzzles Without Acausality

What experiments show: Phenomena like radioactive decay and the double-slit experiment display stable statistical laws. These results are intriguing and puzzling.

Interpretation caution: To leap from these results to the claim of acausality is suspect. The safer conclusion is that we lack a full account of the hidden factors.

Hidden structures: The possibility of undiscovered factors maintains coherence, avoiding the paradox of “uncaused regularity.”

Methodological Consequences

Modeling discipline:

Define boundaries and conditions clearly.

Treat distributions as summaries of specific contexts, not universal truths.

Anchor explanations in interventions and manipulations when possible.

Use probabilities for groups, not for individuals, in complex cases.

Humility: Models are maps. Maps can be accurate and useful, but they are not the territory.

Summary

This essay argues that causality is universal, supported by induction rather than dogma. Randomness signals ignorance, not absence of cause. Because the world is deeply entangled, regularities are rare, and they appear mainly under stabilized conditions. Mathematical probability distributions smooth and summarize long-run patterns under such conditions, and are useful for group predictions, not individuals. Language and mathematics, though indispensable, remain abstractions. The world itself remains beyond full grasp, but within bounded domains we can act effectively.

Readings

Cartwright, N. (1983). How the laws of physics lie. Oxford University Press.

Annotation: Argues that many “laws” function as idealized templates that work only under carefully tailored conditions. Directly supports the essay’s claim that precision is a local achievement of stabilization rather than a universal property of nature. Provides vocabulary for criticizing the reification of mathematical laws outside their domains.

Cartwright, N. (1989). Nature’s capacities and their measurement. Oxford University Press.

Annotation: Introduces the idea that causal powers (“capacities”) manifest only in specific arrangements. Aligns with the essay’s emphasis on bounded situations and predominant factors. Offers a constructive alternative to both global law-worship and acausal rhetoric by grounding probabilistic regularities in situated causal structure.

Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge University Press.

Annotation: Develops the image of a patchwork scientific world in which models and laws work piecemeal. Supports the essay’s claims that regularities are rare, that boundary-setting is essential, and that expecting universal lawlike coverage misconstrues how science succeeds.

Hume, D. (2007). An enquiry concerning human understanding (P. Millican, Ed.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1748)

Annotation: Classic skepticism about perceiving necessary connection and the problem of induction. Serves as a foil for the essay’s inductive defense of causality: while Hume undermines deduced necessity, practical success and stabilization offer a reply based on manipulation and repeatability.

Kant, I. (1998). Critique of pure reason (P. Guyer & A. W. Wood, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1781)

Annotation: Establishes the phenomenon/noumenon distinction and the role of the mind’s structuring in experience. Underwrites the essay’s claim that the “thing in itself” is unknowable and that knowledge proceeds through conceptual and linguistic mediation.

Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Annotation: Formalizes causal inference with interventions and counterfactuals. Connects directly to the essay’s emphasis on controls and manipulable structures. While methodologically distinct from philosophical treatments, it exemplifies how bounded, explicit assumptions enable identification of causal effects.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation. Oxford University Press.

Annotation: Interventionist account of causation: causes are variables that can be manipulated to change effects. Reinforces the essay’s stance that understanding causality is tied to the capacity to control conditions, and that explanation is situational and model-relative.

Jaynes, E. T. (2003). Probability theory: The logic of science. Cambridge University Press.

Annotation: Presents probability as extended logic for uncertain reasoning, with strong emphasis on model assumptions and information constraints. Supports the essay’s treatment of probability as an abstraction whose reliability hinges on stabilized contexts and clearly specified priors and domains.

Kolmogorov, A. N. (1950). Foundations of the theory of probability (2nd English ed., N. Morrison, Trans.). Chelsea.

Annotation: Axiomatizes probability measure theory. Provides the formal backbone for probabilistic modeling while remaining silent about interpretation—thereby illustrating the essay’s point that mathematics requires external, linguistic specification of what is being modeled and under what conditions.

Bohm, D. (1957). Causality and chance in modern physics. Routledge.

Annotation: Critiques interpretations that elevate fundamental chance and explores causal alternatives in quantum contexts. Offers resources for resisting acausal readings of quantum phenomena, aligning with the essay’s boundary problem for “uncaused regularities.”

Reichenbach, H. (1956). The direction of time. University of California Press.

Annotation: Connects probabilistic reasoning, causation, and temporal asymmetry. Relevant to the essay’s interest in aggregates and long-run behavior; illustrates how statistical structure is tied to physical conditions rather than to metaphysical acausality.

Salmon, W. C. (1998). Causality and explanation. Oxford University Press.

Annotation: Surveys causal concepts and explanatory strategies, emphasizing statistical relevance and mechanisms. Complements the essay’s view that probabilistic patterns gain meaning only when anchored to underlying structure and stabilized arrangements.

Mayo, D. G. (1996). Error and the growth of experimental knowledge. University of Chicago Press.

Annotation: Develops a severe testing philosophy that highlights the role of experimental design and control in learning. Strengthens the essay’s methodological prescriptions: stabilization and explicit error probing are essential for trustworthy claims about regularities.

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C., & Scheines, R. (2000). Causation, prediction, and search (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

Annotation: Presents graph-based algorithms for discovering causal structure from data under explicit assumptions. Serves as a concrete example of how bounded assumptions and careful constraints can recover aspects of causality despite entanglement.

Box, G. E. P., & Draper, N. R. (1987). Empirical model-building and response surfaces. Wiley.

Annotation: Classic on building useful models under real-world constraints, emphasizing that “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” Resonates with the essay’s insistence on local precision, stabilization, and the practical, non-universal scope of probabilistic summaries.

Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., & Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Physical Review, 47(10), 777–780.

Annotation: The EPR argument challenges the completeness of quantum mechanics and motivates hidden-variable style responses. Included to articulate how resistance to acausality can be formulated without denying the empirical success of quantum predictions.

Haldane, J. B. S. (1927). Possible worlds and other essays. Chatto & Windus.

Annotation: Source of the remark that the universe may be “queerer than we can suppose.” Cited to mark epistemic modesty while maintaining that intelligible reasoning requires disciplined boundaries and stabilized contexts; the remark tempers hubris without licensing acausal leaps.

Appendix A: On Nomological Machines

A nomological machine is not something that exists ready-made in nature. It is a human creation, an act of imagination and construction. To create one is a creative act with two inseparable parts:

1. The Linguistic–Mathematical Side

This is the model or description.

It requires decisions about what to include and what to leave out.

These decisions arise from prior understanding of the world, from experience, and from theory.

The description is never complete. Some elements may be irrelevant but still included; others that turn out to be crucial may be overlooked. It depends on what thoughts come to mind or are found in discussion.

The result is an abstraction: a way of talking about and symbolizing the causal relations thought to be important.

2. The Physical–Material Side

This is the arrangement of the real-world setup.

The material situation must be designed to reflect the chosen abstraction: background conditions are stabilized, interfering factors suppressed, and relevant variables isolated.

The physical instantiation embodies the model by making it possible to observe the regularities the model predicts.

3. The Creative Act

The act of building a nomological machine involves judgment about what counts as relevant.

These judgments are fallible: the right things may not be included, the wrong things may be. The boundaries may cut across the situation awkwardly.

This incompleteness is inherent, because the entangled world cannot be exhaustively captured.

Yet, the attempt makes regularities visible. The linguistic model and the physical setup support one another.

4. What a Nomological Machine Is

A nomological machine, then, is a hybrid creation:

Linguistic and mathematical abstraction that specifies what should matter.

Physical construction or arrangement that makes those abstractions operative in the world.

Together, they produce a domain where causal regularities become tractable.