Reason: Thinking, Language and Consistency with the World

I return once again to the topic of thinking oneself out of a dripping paper bag. Perhaps things are starting to dry out, but I could still be all wet.

Introduction

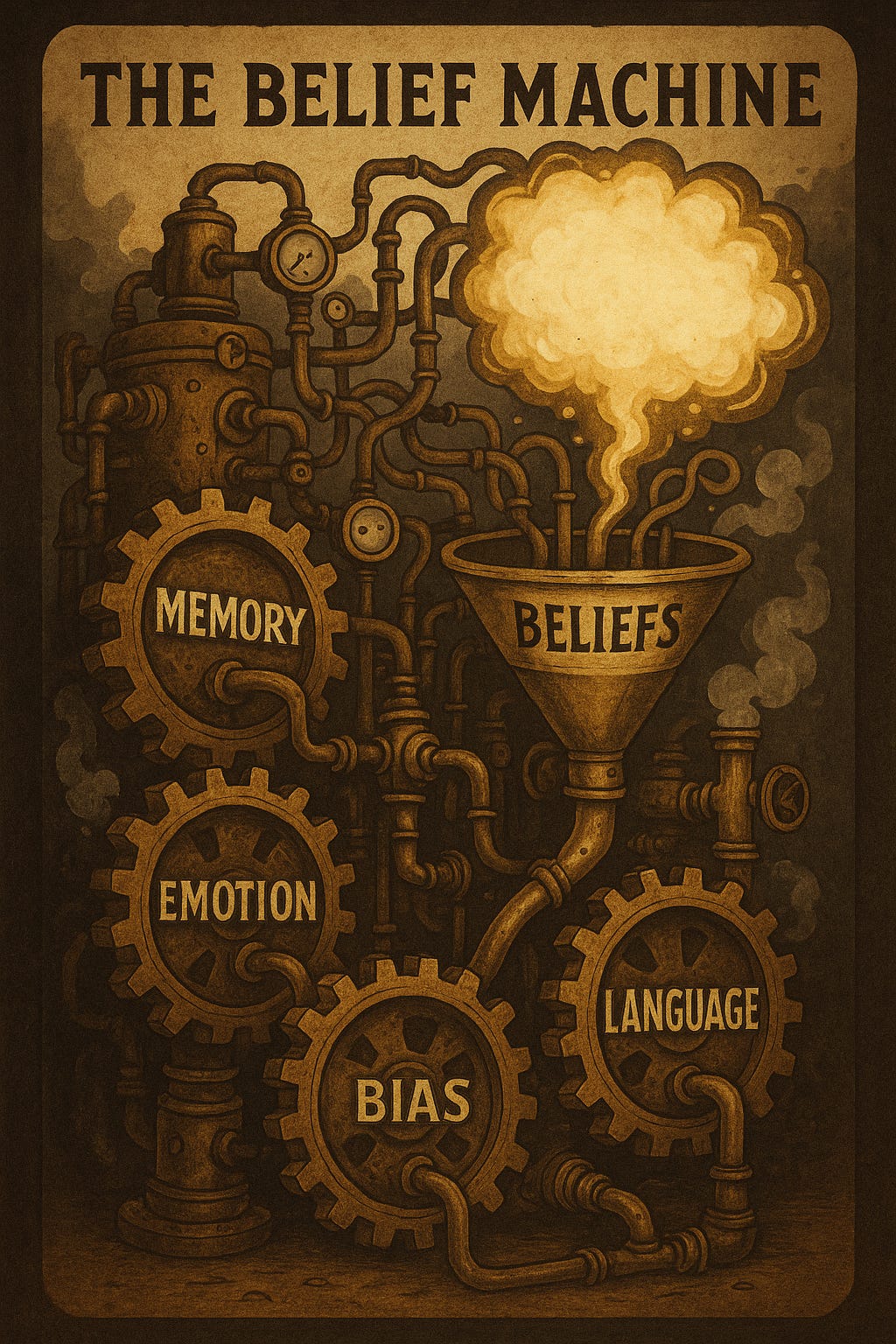

This essay examines the nature of reasoning as an embedded, fallible, and interpretive process rather than a formal or algorithmic one. Reasoning does not begin from neutrality or follow abstract rules; it arises from a pre-existing structure of belief, shaped by memory, experience, emotion, and language. Assertions are formed and tested not through deductive logic alone, but through subjective judgments constrained by plausibility, coherence, and fit with the world as understood. Concepts such as truth, evidence, agency, and justification are interrogated not as metaphysical absolutes but as context-dependent constructions, vulnerable to contradiction, distortion, and misuse. The essay argues that traditional epistemological models—if they fail to account for the actual conditions under which thought occurs—will be supplanted by frameworks grounded in cognitive realism, linguistic awareness, and pragmatic evaluation.

I. Arriving at Reasoning and Testing It Against the World

1. The Problem of Reasoning: Generation and Evaluation

The challenge of reasoning consists of two distinct but interrelated operations: (1) generating candidate thoughts—assertions, explanations, hypotheses—and (2) evaluating those thoughts for consistency with the world. The first task is generative and interpretive. The second is judgmental and corrective. Neither can be reduced to a formal procedure, and neither is guaranteed to succeed.

Reasoning, except in narrow domains such as formal logic or mathematics, is not algorithmic. Outside these systems—where constraints are well-defined and syntactic manipulation is tractable—reasoning is a contingent, uncertain process rooted in memory, perception, language, attention, and interpretation. There is no universal procedure for generating correct thoughts, nor for recognizing when one’s conclusions are accurate. What exists instead is a repertoire of cognitive operations, loosely coordinated and unevenly reliable, shaped by psychological, cultural, and linguistic constraints.

2. Can There Be an Algorithmic Basis for Reasoning?

It is natural to seek an algorithmic basis for reasoning—some structure or procedure that could guarantee the validity or truth of conclusions. But no such structure exists for general reasoning. The desire for algorithmic reasoning reflects a wish for certainty, but certainty is not a feature of thought; it is an affective stance adopted toward conclusions that feel settled.

Reasoning is inherently contingent on prior beliefs, shaped by interpretive frameworks, and inseparable from subjective inference. It must be treated as provisional. But in practice, it rarely is. People routinely treat their conclusions as final, ignoring the psychological and contextual contingencies that shape them. This leads to the illusion of certainty, especially in complex domains where multiple competing assertions coexist, each grounded in different interpretive commitments.

Language compounds the problem. Any position can be stated in a vast number of roughly equivalent ways, and those variations are not neutral. They influence how an argument is understood, what parts are emphasized, and whether it is accepted or rejected. Even when two speakers agree on content, differences in phrasing may lead to divergence in interpretation. Comprehension fails routinely; rejection often occurs not on logical grounds but on linguistic, emotional, or associative ones. The process is messy, unstable, and non-formal.

II. A Taxonomy of Testing for Coherence and Truth

Reasoning operates across a wide spectrum of domains, each with differing levels of epistemic accessibility. Assertions vary not only in content but in the extent to which they can be tested, confirmed, or disconfirmed. What follows is a functional taxonomy of argument types, organized by their degree of testability, grounding in the world, and susceptibility to evaluation.

1. Empirically Testable in Both Theory and Practice

Some arguments can be tested both in principle and in application. These are typically grounded in domains where observable, measurable, and replicable phenomena can be evaluated. Examples include:

Engineering claims ("This material will fail under 3000 psi"),

Scientific hypotheses under experimental control,

Statements about present-tense sensory conditions ("There is a chair in the room").

Such arguments are firmly tethered to the objective world and benefit from operational definitions, instrumentation, and direct feedback. They admit of clear standards of falsification or confirmation.

2. Theoretically Testable but Practically Inaccessible

Other arguments are testable in theory, but not accessible to testing in practice. This may be due to:

Temporal distance (e.g., events in deep time),

Ethical constraints (e.g., experiments on human development),

Technological limitations (e.g., features of unobservable cosmic regions).

These claims can be formally modeled or hypothetically constrained, but their truth or falsity remains unresolved due to barriers to empirical access. They are not metaphysical, but epistemically remote.

3. Unverifiable in Practice and Theory, but Still Meaningful

Some arguments cannot be tested even in principle, yet retain meaning within interpretive or narrative frameworks. Examples include:

Singular historical claims based on fragmentary evidence ("X assassinated Y"),

Subjective reports ("He felt remorse when he acted"),

Situationally bound intentions ("She intended to betray him").

These are not generalizable or empirically reproducible, but they function within discourse communities, legal systems, or moral narratives. Their meaning is contextual and interpretive, not strictly evidentiary.

4. Value-Based or Normative Arguments

Certain claims are strictly evaluative. They do not assert facts but express preferences, judgments, or ideals. Examples include:

"Justice requires equality,"

"It is wrong to deceive even for a good end."

Such arguments are only weakly tethered to the objective world. Their meaning arises from normative discourse frameworks—legal, religious, philosophical, or cultural. While they may refer to empirical consequences, they cannot be verified or falsified in the empirical sense. They "touch the ground" only at select points, where consequences intersect with values (e.g., when evaluating harms or benefits).

5. Unverifiable, Unfalsifiable, and Untethered

At the outermost boundary are claims that cannot be verified or falsified, even in principle, and which exhibit no empirical or inferential contact with the world. These include:

Metaphysical absolutes ("Reality is an illusion created by an undetectable entity"),

Theological or cosmological speculations that make no testable predictions,

Assertions constructed to be immune to all disproof by definitional maneuvering.

Such claims "touch the ground at no points." They are linguistically formed but epistemically inert. Their persistence is due to cultural, emotional, or rhetorical momentum, not their capacity to track reality.

Summary

This taxonomy highlights the graded structure of epistemic accessibility. Arguments range from fully testable to entirely untethered. The capacity to evaluate an assertion depends on its empirical footprint, its conceptual structure, and the interpretive practices within which it is embedded. Many errors in reasoning stem from misclassifying the type of claim being made, treating evaluative or speculative statements as if they were empirical, or mistaking contingent interpretations for necessary truths. Clarity about these categories is essential for any coherent account of reason.

III. Facts and Interpretations

1. Nietzsche and the Myth of Untouched Facts

Nietzsche’s remark that “there are no facts, only interpretations” is often dismissed as rhetorical overreach or philosophical provocation. Yet stripped of polemic, the underlying point is difficult to deny: all facts are encountered through interpretive frameworks. What we take to be a fact is never free of framing, selection, emphasis, and context. The observation is not a denial of reality, but a rejection of the myth that facts are pure, uninterpreted, or self-evident.

A fact must be articulated, classified, and related to a network of beliefs before it can function as such. This act of framing—what counts as relevant, what counts as evidence, what counts as settled—is always an interpretive decision, even if implicit. The claim that interpretation is unavoidable is not radical—it is descriptively accurate.

2. Thinking as Matching Assertions to the World

When encountering a situation, one begins to make assertions about it—descriptive, predictive, causal. These assertions do not arise ex nihilo. They are produced by memory-driven pattern matching: a perceived configuration triggers remembered categories, explanations, or analogies.

This process is automatic and often unexamined. Assertions may be well-grounded or entirely mistaken, but their generation is not guided by rules—it is guided by associative activation and the current state of belief. If the initial assertion appears inadequate, one may revise it, generating new possibilities through reflective attention. This is the process commonly labeled "thinking," although its mechanisms remain largely mysterious and tacit.

3. Example: Revising Assertions Through External Lookup

To illustrate: a conversation about canola oil leads to a series of claims—about its origin, its processing, and its health implications. Doubt arises, prompted by awareness of memory limitations. A lookup is performed—here, through ChatGPT—serving as a surrogate memory or external validator. The information retrieved is tentatively accepted, held with reservation, and used to buttress or revise earlier assertions.

This is an instance of informal argumentation. The process involves:

An initial claim, grounded in memory,

A recognition of potential error,

Consultation of external input, and

A revised belief, accepted provisionally.

The reasoning structure is no different than more formal versions—it is an argument from assertion to revised assertion, shaped by evidence and judgment, though executed informally and without deductive precision.

4. How Do We Come to Think About the World?

Thoughts arise without instruction. Some align with the world; many do not. The metaphor that thoughts emerge like bubbles in soda pop is apt: they surface unpredictably, not by algorithmic command, but through accumulated pressure—stimulus, memory, emotion, attention.

Yet, while spontaneous, thought is not entirely random. One can tilt the bottle—that is, bias the emergence of certain thoughts through deliberate focus, framing, or questioning. The generation of thought is neither free nor fixed; it is constrained emergence, shaped by both internal context and external prompts.

5. From the Stratosphere to the Ground with Argument

At the most abstract level, argument can be seen as a movement from one set of assertions to another, guided by observations, memory, and one’s current understanding of the world. This framing allows for broad generality: argument as transformation, reconfiguration, or alignment within a belief system.

But when descending from this “stratospheric” view, one confronts the messy machinery of cognition. Real reasoning involves countless mental operations: categorizing, analogizing, ordering, filtering, estimating, simulating, contrasting, generalizing, and so on. These operations may be:

Tacit: performed automatically and without awareness,

Deliberate: invoked consciously when problem-solving requires effort,

Formalized: occasionally rendered into rules, diagrams, or algorithms—but rarely in daily reasoning.

No single process governs them all. Thought is layered, opportunistic, and often non-linear.

6. Reasoning Presupposes Belief

All reasoning presupposes an existing framework of belief. There is no neutral starting point, no reasoning from a blank slate. The mind does not operate in vacuum—it operates within a structured background of assumptions, remembered models, and interpretive norms. Reasoning cannot be separated from belief; it is always situated within it.

This is not a limitation but a necessity. To reason is to draw connections from what is already held, even when those beliefs are under revision. That process—where beliefs inform new thought, and new thought reshapes belief—is the core of reflective cognition.

7. The Abstract–Concrete Continuum and the Limits of Language

The terms abstract and concrete are often used as though they describe ontological divisions in the world. But in practice, they are linguistic tools—descriptors of how ideas are framed, not of how reality is structured. The distinction is not binary; it is a continuum, and perhaps not just one, but many.

Some concepts are tightly coupled to observable particulars—e.g., “a red apple.” Others are loosely connected or completely unmoored—e.g., “freedom,” “value,” “infinity.” Words may slide along the continuum depending on context. They can be precise and well-anchored, or vacuous and metaphysical. What matters is not the label but the degree of tethering to objective reference points.

If a term fails to touch the ground at all—that is, if it has no observable consequence, no testable implication, no common referent—then it is arguably meaningless in epistemic terms. Language is a system of signs; without a world to refer to, the signs collapse into self-reference.

8. Reasoning Is Shaped by Emotion and Bias

Reasoning is never neutral. It is enabled, constrained, and directed by emotion, motivation, and bias. These are not external pollutants to a pure reasoning core—they are built into cognition itself.

Emotion highlights what is salient.

Bias structures what is believed to be plausible.

Motivation filters what is pursued and what is dismissed.

These forces affect what is considered, what is remembered, how conclusions are formed, and what gets accepted as justified. Reasoning does not float above them—it flows through them.

Summary

Interpretation is not a feature of some thoughts; it is a condition of all thought. Assertions about the world are framed within beliefs, generated through memory, and shaped by emotion and language. There is no view from nowhere. Reasoning is grounded in belief, directed by affect, and expressed through language whose terms are always partial and contingent. Whether arguing at a high level of abstraction or grappling with immediate particulars, one is always interpreting. Facts do not exist in isolation—they are selected, named, related, and assessed, all within systems of meaning. Reasoning, therefore, is not an algorithmic pursuit of truth, but an embedded, interpretive, and fallible engagement with the world.

IV. On Intelligence, Overconfidence, and the Limits of Formal Ability

1. The Overestimation of Intelligence

Occasionally, individuals make strong claims about the superiority of their reasoning, often grounded in their perceived intelligence or problem-solving ability. One recent instance involved a self-described “bright” individual who insisted his thinking was sound and logical on the grounds that he was simply better at it than others.

The assertion raises obvious epistemological concerns. What does it mean to be “better” at reasoning? By what standard is this judged? If the claim is not reducible to deductive logic—and it rarely is—then the claim must rest on perceived consistency with the world, or more vaguely, on a sense of epistemic superiority. But unless such consistency can be empirically validated, or the reasoning clearly mapped to observable outcomes, the claim is just one among many. It becomes he said–she said, with no adjudicating framework beyond rhetorical posture or social authority.

Thus, while the speaker may believe in their cognitive superiority, that belief, absent demonstrable reliability or predictive success, is epistemically vacuous. It may be true, or it may be bullshit in the technical sense—an assertion made with indifference to its truth value, aimed more at persuasion than at substantiation.

2. Is Reasoning Skill Measured by IQ?

It is often assumed that people who score highly on intelligence tests—especially those involving abstract reasoning, pattern recognition, or logical puzzles—possess superior general reasoning ability. On this view, IQ functions as a proxy for thinking competence across all domains.

This is a questionable assumption. Intelligence tests measure the ability to solve well-structured, closed-system problems, where rules are explicit, conditions are constrained, and answers are singular and defined. But most real-world problems—those found in history, ethics, policy, literature, philosophy, or even social interaction—are ill-structured, ambiguous, open-ended, and saturated with value conflict and incomplete information.

The skillsets required to excel in IQ-type tasks are not the same as those needed to reason effectively in such environments. High scorers may be adept at solving puzzles under constraint, but that does not entail a superior capacity to interpret complex evidence, navigate epistemic uncertainty, or detect conceptual incoherence in messy domains.

The claim that IQ correlates with real-world reasoning success is therefore a supposition, not an established truth—and a weakly supported one at that. Evidence from decision-making studies, cognitive bias research, and real-world performance suggests that intelligence as measured by standard tests does not reliably predict epistemic virtue, judgment quality, or philosophical acumen.

3. Summary

Claims of intellectual superiority often rest on vague or circular reasoning, particularly when they invoke intelligence without reference to method or outcome. The belief that some individuals are “just better” at reasoning is common, but untestable unless grounded in observable success, external consistency, or disciplined method. Absent such grounding, the assertion is not an argument, but a rhetorical gesture—one that may function socially but fails epistemically.

Similarly, the conflation of intelligence test performance with general reasoning ability rests on a category error. IQ tests measure performance in idealized, rule-bound contexts; real-world reasoning is contextual, interpretive, fallible, and embedded in uncertainty. The assumption that competence in one transfers to the other is a convenient illusion, contradicted by both theory and evidence. In complex domains, the signal of intelligence is often masked by bias, language, and belief, leaving even high-ability individuals vulnerable to error. Intelligence may help—but it does not guarantee insight, and it does not substitute for judgment.

The Metaphysical Mire

We can also look at claims which can neither verified nor falsified, and say that their truth value is indeterminate, or perhaps that they are without meaning. I favor the latter interpretation. I also include these problematic aspects of assertions found in the metaphysical mire:

1 – Unverifible assertions

2 – Unfalsifiable assertions

3 – Infinite Regress

4 – Circularity

5 – Category Mistakes

6 – Reification

Detecting Error by Way Of Implausibilty

We can also argue for plausibility or implausibility using either assertions about how the world works, and sometimes calculations to show plausibility or implausibility. Engineers often call these heuristics "back of the envelope" but they do not necessarily involve calculation.

Internally Contradictory Arguments

We can discount an argument that contains an internal contradiction that is A and not A. Of course, we will seldom see such a blatant contradiction directly displayed, but perhaps sometime such contradictions may exist in an indirect fashion.

Sheriff: “Did you steal the mule?”

Yokel: “No sir, I never laid eyes on that mule. And besides, I brought it back the next day.”

1. Classic Legal Contradiction

“I didn’t shoot him! And anyway, he started it.”

A denial of action is immediately followed by a justification of the action. The second clause presupposes what the first clause denies.

2. Denial with Contingent Admission

“I don’t even know the woman. And if I did, I certainly never sent her those letters.”

This tries to pre-emptively close all avenues of accusation but in doing so, simultaneously acknowledges their plausibility.

3. Conditional Non-Denial

“I never touched a drop of alcohol that night—at least not after midnight.”

A qualified denial reframes the claim so narrowly that it undermines the apparent intent of denying the action.

4. Folk Wisdom Variant

“I never lie. And even if I did, I’d be telling the truth right now.”

This plays with self-referential contradiction, much like the liar paradox, but in a conversational rather than formal context.

Indirect or Non-Joking Versions

Outside of humor, such contradictions can and do appear, often unintentionally, especially when:

A. Statements Are Spaced Apart

Contradictions may be separated in time or context. A political figure might say on Monday:

“We will not send troops abroad.”

And on Friday:

“We are deploying a peacekeeping force.”

Each statement might be defended individually, but together they contradict under a consistent interpretation of terms.

B. Terms Are Redefined Mid-Argument

“We are absolutely committed to transparency. But we can’t release that report because it would confuse the public.”

Transparency is affirmed but undermined by pragmatic exemption. This is not overtly self-contradictory but reveals an incoherent commitment.

C. Presuppositional Contradiction

“Science proves that science cannot be trusted.”

This undermines its own basis—using a method to discredit itself—a kind of pragmatic contradiction that collapses under scrutiny.

Why These Are Often Undetected

Ambiguity in natural language allows contradictory meanings to coexist temporarily without immediate detection.

Pragmatic shielding: contradictory statements are often embedded in rhetorical contexts—hedged, qualified, or shifted across different domains.

Memory and attention limitations make it difficult for listeners to track earlier claims once later ones are introduced.

Detecting Error by Way Of Physical Impossibility

Sometimes we can find a lack of truth in an argument when physical impossibilities are raised - the accused was 500 miles away when the crime was committed and could not physically done it. However, if in the same room at the time of the crime, other arguments would have to be used. this is basic and obvious and does not even need to be justified further.

Not Always a Clean Boundary

Sometimes there is no hard borderline between impossible and implausible. For instance, 50 K in a day - highly possible. 100 K in a day, maybe, but not if the walker weighs 300 pounds and is 5 foot 8 inches, impossible, if the claim is 300 k in a day? How do we tell? Only with reference to our current understanding of the world, although in borderline cases, it may need more investigation.

VI. Lines of Evidence, Cumulative Argument, and the Mystery of Reasoned Transitions

1. Structured Argumentation and Subjective Judgment

Even the most structured approaches to argumentation—such as lines of evidence or cumulative argumentation—ultimately rely on human judgment. These frameworks are intended to organize and weigh support for a claim by assembling multiple, independent, or converging pieces of evidence. However, the underlying operation—determining whether evidence is consistent or inconsistent with an assertion—is not algorithmic. It is an act of interpretive assessment, grounded in memory, expectation, framing, and plausibility.

To claim that an assertion is “supported” by a line of evidence presupposes a judgment that each element in the chain is relevant, reliable, and convergent—and that judgment is subjective, even if informed by training or disciplinary norms. There is no universal metric for evidential sufficiency outside specific technical domains. Outside formal systems, judgment remains central, and that judgment is not formalizable in the way logic or arithmetic is.

Large language models (LLMs) and related computational systems may appear to simulate such judgments, but whether they genuinely perform reasoning—or merely mimic it through pattern matching—is an open question. At present, no model has demonstrated that subjective coherence and inference—grounded in embodied, temporal, and interpretive experience—has been captured in computational terms. Whether such a transformation is possible remains to be determined.

2. The Category Error: Thought vs. Probability

It is a category mistake to equate subjective judgment with numerical probability. Human judgment is not a matter of assigning numbers to likelihoods, even when post hoc quantification is attempted. Probabilities are formal entities derived within a mathematical system; judgments about plausibility, on the other hand, are psychological constructions influenced by analogy, narrative, emotional valence, memory bias, and contextual constraint.

To conflate the two is to confuse thinking with calculation. Reasoning about the world involves a tacit balancing of considerations, not the manipulation of well-defined functions. Assigning a number to a belief does not make the belief more rational or better supported—it makes it look more precise, while obscuring the imprecision of the underlying cognition.

3. Common Sense Implication and the Unformalizable Core

In many cases, reasoning proceeds through what might be called common sense implication. One moves from a set of assertions—call them A—to another assertion or set, B. This process is not deductive in the formal sense, but intuitively inferential. It draws upon analogy, familiarity, causal expectation, and world knowledge.

Unlike formal implication, which depends on strict syntactic rules and truth-preserving transformations, common sense implication is elastic, context-dependent, and non-reconstructible in most cases. People do it automatically and frequently—and often badly—yet they seldom reflect on what this ability involves. The transition from one idea to another appears seamless, but how it works remains opaque.

This everyday act of moving from premises to conclusion, often without awareness of the mechanisms involved, is the very core mystery of reasoning. It cannot be reduced to algorithm, yet it is neither random nor arbitrary. It is constrained emergence, grounded in cognitive habits and interpretive frames, but not governed by explicit rules.

Summary

Even in structured argumentation, judgment remains central—and judgment is not computable in any established sense. Whether building a line of evidence or layering a cumulative case, one must assess relevance, coherence, and convergence—all subjective and interpretive acts. Attempts to map this onto probability risk conflating fundamentally different modes of cognition: thought and calculation. And beneath even the most basic inferences lies a deeper mystery—the fact that humans routinely move from idea to idea, assertion to conclusion, without knowing how. This transition, unformalizable and mostly unconscious, is the heart of reasoning—ubiquitous and indispensable, yet never fully grasped.

VII. The Self-Contradiction of Uncaused but Constrained Events

1. A Linguistic Contradiction Masquerading as Physics

There are claims in modern physics—particularly in interpretations of quantum mechanics—that posit ontologically uncaused events which nonetheless display stable statistical regularities. These events are said to be random in principle, not merely unpredictable due to hidden variables or measurement limitations, but fundamentally uncaused. At the same time, they conform to precise probability distributions.

This pairing of uncausedness with statistical constraint is, from a linguistic and conceptual standpoint, incoherent. It attempts to assert pure contingency and structured regularity in the same breath. If events are truly uncaused, it is unclear what grounds the emergence of reliable patterns. If reliable patterns exist, one must ask what enforces them, and whether that enforcement implies some hidden or unacknowledged structure.

The claim is not contradictory in the formal sense—it does not reduce to “A and not A” in strict logical terms—but it collapses semantically when examined. The terms involved—“uncaused,” “random,” “lawlike,” “probabilistic”—are imported from incompatible conceptual domains and forced into syntactic proximity without conceptual coherence.

2. Epistemic Breakdown: Language, Mind, or Conceptual Overreach?

If the claim about uncaused regularities is in fact an accurate reflection of how the objective world behaves, then at least one of the following must be true:

Our language fails to describe this kind of reality.

Our minds are unable to model such conditions coherently.

The conceptual framework itself is flawed, and the incoherence is in the claim, not in our ability to grasp it.

This forces a choice: is the failure in the world, the model, or the cognitive apparatus used to interpret it?

From a pragmatist standpoint, the answer is clear: such a claim is epistemically illegitimate. It does no explanatory work, it yields no operational insight, and it cannot be tested beyond the probabilistic surface it tries to explain. It purports to describe the nature of reality but instead constructs a metaphysical overlay on an otherwise functional formalism.

A claim that cannot be integrated into thought except by paradox, evasion, or semantic contortion is not a mysterious truth; it is a category mistake. The statement that events are uncaused yet follow a lawlike distribution is not deep—it is confused.

VIII. Agency, Free Will, and the Fiction of Just Deserts

1. Agency, Smagency: A Critique of Terminological Inflation

The term agency—now common in philosophy, the social sciences, and psychology—is often a rebranded version of what was once called free will. Its adoption introduces a semantic inflation that obscures more than it clarifies. While the word suggests a capacity to act, choose, or initiate behavior, it is laden with polysemous implications and ambiguous boundaries.

In ordinary discourse, to say someone exercised agency means little more than that they formed an intention and acted upon it. But this is quickly complicated:

At the physical level, agency is clearly situational and constrained—bodily limitations, environmental obstacles, and social structures all limit what can be done.

At the emotional or psychological level, agency is often shaped by internal states not fully accessible to awareness or control.

At the metaphysical level, the term begins to drift: agency is now said to imply some non-causal freedom, some uncaused cause, or self-originating action—a view that is unverifiable, unfalsifiable, and epistemically empty.

This final usage veers into what Wittgenstein would call a language game detached from practice. Assertions about metaphysical free will masquerade as deep insight but collapse upon scrutiny, offering no operational criteria, no testability, and no coherent definition outside their rhetorical function.

2. Classifying Positions on Free Will and Determinism

The debate over free will and determinism remains unresolved, in part because the terms are often ill-defined and inconsistently applied. A coherent taxonomy includes the following positions:

Incompatibilism: Free will and determinism cannot coexist. If determinism is true, then free will is an illusion.

Compatibilism: Free will is possible within a deterministic framework. Constraints do not eliminate the capacity for intentional action.

Hard Compatibilism: Free will not only coexists with determinism but requires it. Without causal continuity, the notion of agency dissolves.

Conceptual Disconnection: Free will and determinism are unrelated categories; the supposed conflict arises from category error.

Skeptical or Eliminativist View: Free will is incoherent or implausible, given what is known about psychological and environmental constraints.

Each of these positions involves interpretive choices about the meaning of will, causality, and personhood. None is established by empirical data alone; all involve philosophical commitments regarding what counts as explanation.

3. Just Deserts and the Fiction of Moral Ontology

The idea of just deserts—that individuals deserve punishment or reward in proportion to their moral conduct—presumes some connection to free will. But this connection, like free will itself, is unstable and contested.

Competing views include:

Incompatibility: Just deserts makes no sense without metaphysical free will; if free will is illusory, so is moral desert.

Compatibility: Just deserts is preserved under compatibilist assumptions; agents can be responsible even if their actions are determined.

Dependency: Just deserts requires free will; moral responsibility is unintelligible without the capacity to have done otherwise.

Disconnection: Just deserts has no necessary relationship to free will; it functions independently within legal or social systems.

Incoherence (the position advanced here): Just deserts is a metaphysical fiction, without ontological grounding, maintained only within institutional and psychological frameworks of belief.

On this view, moral desert is not a feature of the universe. It is a narrative device, a cultural construction, and a rationalization for punishment. To say someone "deserves" a particular fate is to speak within a specific linguistic and institutional practice, not to state an objective fact. The persistence of the concept reflects emotional habits and legal conventions, not metaphysical reality.

Just deserts, like metaphysical agency, fails the test of epistemic legitimacy. It does not describe a property of persons or actions. It projects judgment outward, cloaking psychological reaction in the garb of moral truth.

Summary

The concepts of agency, free will, and just deserts are saturated with conceptual confusion, linguistic ambiguity, and metaphysical overreach. Once stripped of their rhetorical force, what remains is a set of interpretive practices—not discoveries about the world, but language games built to coordinate behavior, justify systems, and rationalize punishment. Assertions about metaphysical freedom and moral desert offer no explanatory gain. They are culturally entrenched but epistemologically hollow—linguistic habits mistaken for ontological insight.

IX. Will History Vindicate Me? On Belief, Reasoning, and Epistemological Consequence

Modern epistemology, if it is to remain intellectually viable, must grapple with the kinds of insights developed throughout this discussion. If it fails to do so, it risks historical obsolescence—not through polemic refutation, but through accumulated irrelevance. An epistemology that ignores how reasoning actually occurs—situated in belief, driven by memory, shaped by emotion, and mediated by language—will become an artifact of academic formalism rather than a guide to inquiry.

The foundation is simple and inescapable:

To reason at all requires a pre-existing set of beliefs about the world.

This is not a contingent psychological fact; it is a conceptual necessity. Without beliefs—without expectations, categories, generalizations, or memories—no reasoning process could even begin. One cannot evaluate a claim, weigh evidence, or generate a counterexample without some prior model of how the world works.

Among those beliefs, some will turn out to be true—at least in the practical sense of being consistent with experience and predictive success. But in any domain of complexity—psychology, economics, morality, history, politics—it is almost guaranteed that many beliefs will be wrong. This is not a matter of pessimism; it is a basic inductive observation. When thousands of mutually contradictory claims are advanced, most must be incorrect. There is no epistemic pluralism strong enough to accommodate simultaneous incompatibilities.

Directed but Random Thought: The Architecture of Reasoning

Whether the task is to explain or to refute, the process begins with the production of thought. Thought arises in a form that is neither strictly random nor strictly determined—it is directed, but not rule-governed. It emerges from a system saturated with:

Memories of prior experience,

Stored analogies,

Fragments of language and image,

Emotional relevance,

Contextual cues.

What emerges as reasoning is a kind of patterned improvisation—guided but unpredictable, shaped by structure but never reducible to it. The mind seeks coherence with its own model of the world, even when that model is fragmentary, biased, or mistaken.

In this way, all reasoning is a negotiation between what is already believed and what is newly proposed. The process is fundamentally interpretive and comparative. It is neither algorithmic nor arbitrary. And it is always bounded by the cognitive materials at hand—the accumulated impressions, narratives, and justifications that constitute a working picture of the world.

Conclusion

If history does vindicate anything, it will not be the preservation of traditional epistemology in its unmodified form. It will be a turn toward an epistemology of situated cognition—one that recognizes the inevitability of belief, the fallibility of judgment, the opacity of thought generation, and the centrality of interpretive structure.

Reasoning is not the manipulation of abstract symbols in pursuit of timeless truth. It is the embodied act of navigating a world of uncertainty using inherited tools, provisional models, and constrained creativity. The recognition of this fact is not a retreat from rigor; it is the precondition for developing a theory of knowledge that is not a fiction. An epistemology that denies these constraints may survive in journals and syllabi. But in the world of thought that matters, it will be consigned to the dustbin of historical misdescription—not by denunciation, but by its increasing failure to illuminate the conditions under which reasoning actually occurs.