Reason: Tagging and Classifying Assertions for Retrospective Analysis and the Limits of Structural Formalism

On the Theoretical Origins, Practical Constraints, and Epistemological Ambiguity of Argument Tagging Systems

Author’s Preface

The practice of tagging or classifying the components of natural-language arguments has gained traction in certain academic domains, particularly in discourse analysis, informal logic, and computational argument mining. These practices are largely retrospective—they analyze discourse after the fact. Despite offering some insight into how arguments are built and how they function, these systems present substantial difficulties in both their application and their relevance to real-world reasoning. This essay traces the intellectual lineage of these systems, examines their typical classification schemes, and evaluates their practicality. The conclusion drawn is that while such systems may contribute to a better understanding of argumentation, they remain interpretive, highly subjective, and largely unsuitable for real-time argument construction.

Introduction

Arguments, when spoken or written in natural language, rarely follow formal structures. Nevertheless, some academic fields have attempted to parse and classify them by identifying their components and tagging each one according to its argumentative function. This essay examines the origins, structure, and limitations of such classification systems. It begins by reviewing several key frameworks developed in rhetorical studies, informal logic, and computational linguistics. It then analyzes the feasibility of applying these systems to everyday argumentation. Finally, it addresses the cognitive demands and epistemic challenges involved in tagging arguments, concluding that while conceptually interesting, these methods are best reserved for theoretical analysis and not practical application.

Discussion

1. Origins in Rhetoric and Logic

The impulse to classify parts of an argument originates with classical rhetoric and the later development of formal logic. Aristotle distinguished between logos (reason), pathos (emotion), and ethos (character), and the rhetorical syllogism (enthymeme) became a staple of argumentation theory. However, the modern movement toward tagging discrete components within natural-language discourse finds its roots in three twentieth-century developments:

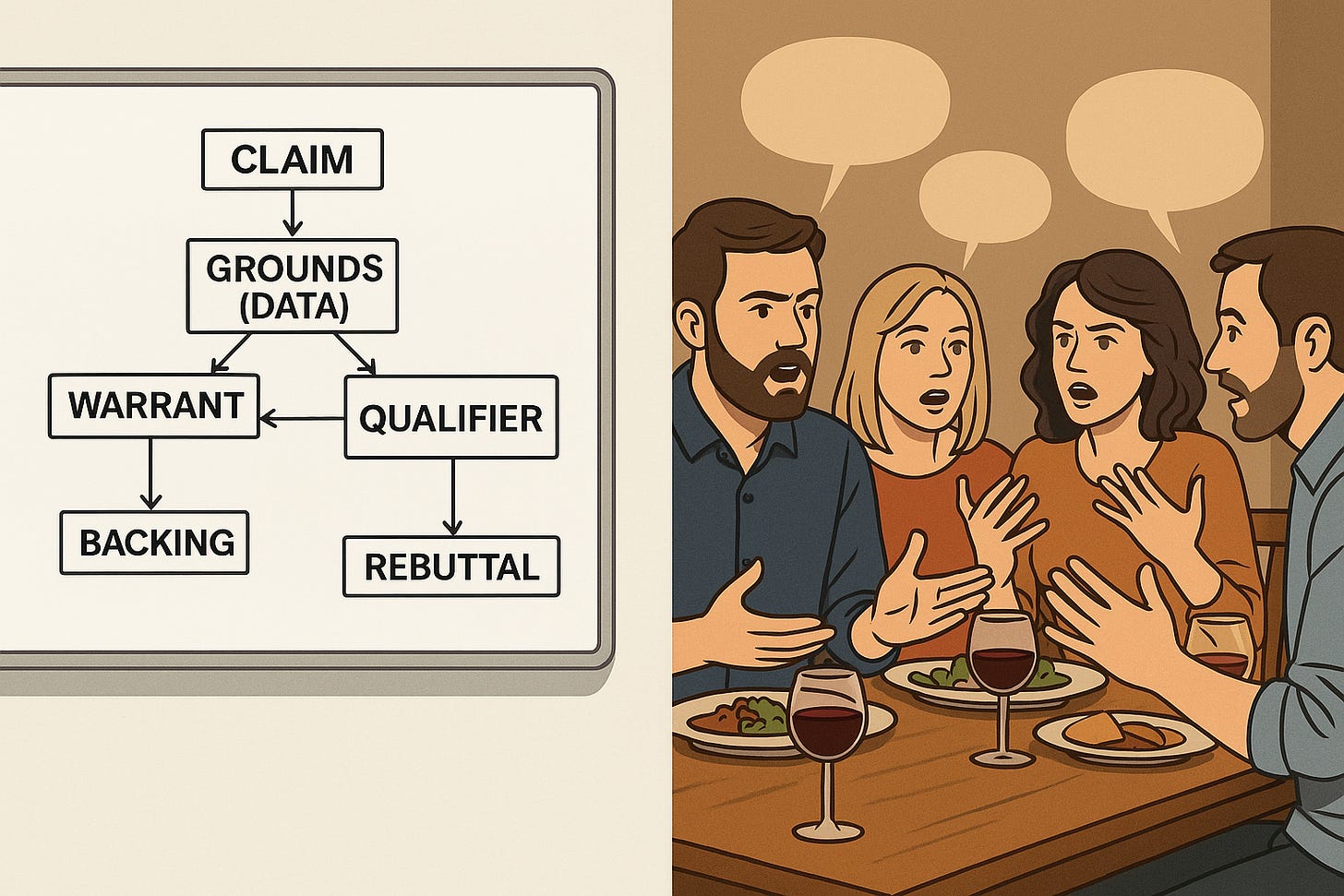

Stephen Toulmin's Model of Argumentation (1958) :

Toulmin proposed that real arguments do not resemble formal logic but consist instead of more flexible and functionally diverse components. His model introduced:Claim: The conclusion or point being asserted.

Data (or Ground): The evidence used to support the claim.

Warrant: The principle or assumption that connects the data to the claim.

Backing: Justification for the warrant.

Qualifier: An indication of the strength or modality of the claim.

Rebuttal: Anticipated counter-arguments or exceptions.

This model laid the groundwork for later efforts to tag argumentative statements with functional roles.

See Appendix C – Some Short Worked Examples of the Toulmin Method

Pragma-Dialectical Theory (Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984 onward):

Built on speech act theory and dialogue logic, this system seeks to model rational discourse as a process of resolving disagreement. It identifies moves within a critical discussion, such as putting forward a standpoint, challenging a premise, or requesting clarification. The emphasis is procedural, aiming to evaluate whether discourse adheres to rational norms.Computational Argument Mining (21st century):

The advent of natural language processing has led to attempts to automatically identify argument structures within large text corpora. Researchers in this field annotate texts with tags denoting component types (e.g., claim, reason, rebuttal) and train machine learning systems to replicate these annotations. These efforts depend on pre-existing taxonomies derived from Toulmin and pragma-dialectics but involve additional categories suited to automated analysis, such as stance, modality, and argument span.

2. Typical Classificatory Categories

Across these traditions, argument components are tagged into recurring categories. While terminology varies, the functional roles generally align. These include:

Assertion/Claim/Conclusion: The proposition being defended.

Premise/Reason/Evidence: Statements intended to support the claim.

Warrant (Toulmin): The bridge between premise and conclusion, often left implicit.

Backing: Supporting evidence for the warrant.

Qualifier/Mode: Indicates strength or certainty—e.g., “possibly,” “likely,” “certainly.”

Rebuttal/Counterclaim: Acknowledgement or anticipation of opposing views.

Modality: Sometimes treated separately from qualifiers, encompassing expressions of necessity, probability, obligation, or permission—e.g., “must,” “may,” “might.”

Additional classifications introduced in computational models include:

Stance: Whether the speaker supports or opposes a proposition.

Argument Function: Whether a statement introduces, supports, rebuts, or summarizes a position.

Argument Span: How many sentences or clauses form a unit of argumentative force.

These classifications are largely heuristic. The same statement might be tagged differently depending on the analyst’s interpretive lens.

3. Application Constraints and Cognitive Demands

a. Retrospective Nature of the Method

These tagging systems are inherently retrospective. They require that an argument already exist in textual form and be sufficiently coherent for analysis. Most arguments encountered in everyday life—especially in conversation, interviews, speeches, or social media posts—do not conform to clean structures. They are:

Redundant

Implicit

Elliptical

Emotionally colored

Lacking explicit logical connectors

Attempting to retrofit these fragments into a structured format often demands significant reconstruction, including:

Inferring unstated premises

Rewriting for clarity

Disambiguating pronoun references

Clarifying the speaker’s intended meaning

This process is interpretive, not mechanical, and introduces subjective decisions at every step.

b. Practical Use in Argument Construction

While one could, in theory, attempt to craft arguments using these classifications, doing so would be cognitively demanding and time-intensive. Unlike formal deduction, these systems offer no automated inference mechanism. Each element must be manually constructed, labeled, and tested for coherence. For most real-world applications, such as persuasive writing, debate, or spontaneous speech, this is an implausible burden.

Furthermore, the effort required would likely exceed the communicative benefit. Most listeners or readers do not expect, recognize, or reward formally tagged structure. The practice becomes self-referential—valuable only to the analyst conducting the tagging.

4. Ambiguity and Subjectivity of Classification

a. Fuzzy Boundaries Between Categories

There are no rigid, universally accepted rules for how to tag components. Consider the sentence:

“It’s probably going to rain, so take an umbrella.”

Is this a claim about weather or an advice act?

Does “probably” act as a qualifier, a modal operator, or an epistemic hedge?

Is “so take an umbrella” a conclusion, a practical inference, or a directive?

The answer depends on the purpose of analysis: logical form, speech act function, or communicative intent.

b. Dependence on Experience and Judgment

Tagging requires not just comprehension of language, but interpretive competence: the ability to reconstruct the speaker’s intention, identify implicit assumptions, and discern argumentative structure. This makes the method inaccessible to novices and dependent on the skill and training of the analyst.

Even among experts, agreement is imperfect. Studies of inter-rater reliability in annotation projects often show substantial divergence unless participants are trained on the same guidelines and examples. This undermines the claim that the categories are objective or robust.

For more information, see Appendix A – Some Resources

Summary and Conclusion

Tagging assertions with classificatory labels—such as claim, reason, qualifier, or rebuttal—offers a framework for analyzing argument structure in a theoretical or computational context. These systems originate in academic traditions such as Toulmin’s model of informal logic, pragma-dialectics, and the recent developments in argument mining. They provide a vocabulary for describing how arguments function and what roles different parts play.

However, the application of these systems is almost entirely retrospective. Natural-language arguments rarely present themselves in structured form, and efforts to impose structure require extensive interpretation, rewriting, and paraphrasing. The categories themselves are flexible, overlapping, and often arbitrary in borderline cases. While the systems may offer insight into patterns of reasoning and help train awareness of rhetorical structure, they are impractical as tools for either real-time argument construction or large-scale discourse analysis without automation.

In conclusion, tagging assertions is a method of descriptive formalism: it illuminates after the fact, but offers little guidance before the fact. Like the study of fallacies, it may cultivate critical awareness, but cannot furnish a formula for successful persuasion or clear communication.

Suggested Readings (APA Format, Lay-Accessible)

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. Random House.

→ Explores how structure, clarity, and coherence enhance message retention and impact.Levitin, D. J. (2016). A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age. Dutton.

→ Provides tools for analyzing claims and evidence in public discourse.Weston, A. (2018). A Rulebook for Arguments (5th ed.). Hackett Publishing.

→ Offers concise guidance on how to understand and evaluate everyday arguments.Fisher, A. (2004). The Logic of Real Arguments (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

→ Analyzes natural-language reasoning with attention to structure and context.Tindale, C. W. (2007). Fallacies and Argument Appraisal. Cambridge University Press.

→ Discusses how flawed reasoning can be identified through structural analysis.

Appendix A – ChatGPT’s Limited Capabilities for Tagging Text

In principle, ChatGPT can attempt to tag an article using the Toulmin method, but several caveats must be acknowledged:

1. Nature of the Toulmin Model

The Toulmin model involves identifying the following components:

Claim – The main conclusion or assertion.

Grounds (Data) – The evidence or reason offered in support of the claim.

Warrant – The (often unstated) principle or reasoning that connects the grounds to the claim.

Backing – Support for the warrant (e.g., a theory, principle, or authority).

Qualifier – A word or phrase indicating the strength of the claim (e.g., “probably,” “almost certainly”).

Rebuttal – An exception, condition, or anticipated objection.

These are functional roles, not grammatical categories, and context-sensitive, often implicit rather than explicitly marked. This makes reliable tagging difficult, even for trained human analysts.

2. Capabilities of ChatGPT

a. Strengths

Can identify explicit claims, reasons, and qualifiers when clearly stated.

Can often infer warrants when arguments are well-structured and logically coherent.

Can reconstruct implied components with reasonable interpretive inferences.

Can produce annotated versions of arguments, labeling the parts according to Toulmin’s scheme.

b. Limitations

Ambiguity and Subjectivity: Many components (especially warrants and backing) are implicit and open to interpretation. ChatGPT, like human annotators, must guess the author's intent based on context.

Multiple plausible analyses: The same passage can be tagged in different valid ways depending on assumptions about purpose, audience, and implied background knowledge.

Over- or under-inference: The model may generate warrants or backing that are plausible but not necessarily what the author had in mind, or it may overlook unstated assumptions that a human might notice.

No grounding in authorial intent: ChatGPT lacks access to the author’s actual reasoning, only to what is textually present.

3. Empirical Evaluation

No version of ChatGPT is trained specifically or rigorously tested for Toulmin tagging accuracy against benchmarked corpora. Argument mining researchers have developed datasets annotated with Toulmin-style components (e.g., in student essays or debate texts), and even state-of-the-art systems show moderate inter-annotator agreement and partial automation success. Performance varies by:

Genre (editorials vs. debates vs. legal texts)

Structure (explicit vs. informal reasoning)

Complexity (simple vs. recursive argument layers)

No automated system, including ChatGPT, has demonstrated consistent reliability across diverse domains without human supervision.

4. Practical Use Case

ChatGPT can be used exploratorily, not authoritatively, to:

Suggest likely tags in structured or semi-structured texts.

Illustrate the Toulmin model on short passages.

Support teaching or training by offering plausible decompositions.

Assist in identifying where an argument might lack a warrant or backing.

However, it cannot serve as a reliable tagging tool for scholarly use without human interpretation and correction.

Conclusion

ChatGPT can approximate Toulmin tagging in a provisional and interpretive fashion, especially when the argument is relatively simple and its components are explicitly or conventionally stated. However, due to the model’s limitations in interpreting unstated assumptions, disambiguating rhetorical structures, and resolving context-dependent meanings, its performance remains inconsistent and non-reliable for rigorous analytic purposes. It may assist exploratory work or pedagogy, but not substitute for trained human judgment.

Appendix B – Some Resources

Here is a revised list of publicly available annotated examples and explanations of the Toulmin model of argument, with full, explicit URLs provided:

1. Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL)

Provides a sample argumentative essay with annotations identifying Toulmin components such as claim, data, warrant, and rebuttal. Useful for understanding how the model applies to student-level writing.

URL:

https://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/organizing-your-argument/organizing-your-argument-sample-toulmin-argument/

2. Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL)

Offers a conceptual overview of the Toulmin model, along with examples and diagrams. While the examples are not deeply annotated, they provide structural clarity on each component’s role.

URL:

https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/historical_perspectives_on_argumentation/toulmin_argument.html

3. San José State University Writing Center

This PDF handout includes a concise explanation of the Toulmin method, with labeled example arguments and color-coded parts for clarity.

URL:

https://www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter/docs/handouts/Toulmin%20Model%20of%20Argumentative%20Writing.pdf

4. University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) Writing Center

A clear and pedagogically focused explanation of the Toulmin model with practical examples, aimed at helping students structure arguments in academic writing.

URL:

https://www.utsa.edu/twc/documents/Toulmin%20Model%20of%20Argumentation.pdf

These resources are suitable for non-specialists and serve both explanatory and instructional purposes. They illustrate how natural-language arguments can be retrofitted with structural labels and show the interpretive decisions often involved in such tagging.

Appendix C – Some Short Worked Examples of the Toulmin Method

Below are several short worked examples of Toulmin-style argument tagging. Each example includes a brief natural-language argument followed by an explicit breakdown into Toulmin’s components: Claim, Grounds (Data), Warrant, Backing, Qualifier, and Rebuttal, where applicable.

Example 1

Text:

"She must be allergic to strawberries, because every time she eats them, she breaks out in hives."

Toulmin Breakdown:

Claim: She must be allergic to strawberries.

Grounds (Data): Every time she eats them, she breaks out in hives.

Warrant: Allergic reactions often cause hives after exposure to the allergen.

Backing: Medical literature establishes hives as a common allergic response.

Qualifier: Must (strong likelihood)

Rebuttal: Unless something else in the meal is causing the hives.

Example 2

Text:

"We should avoid hiking this weekend because the forecast says it will rain heavily."

Toulmin Breakdown:

Claim: We should avoid hiking this weekend.

Grounds (Data): The forecast says it will rain heavily.

Warrant: Hiking in heavy rain is unpleasant or potentially unsafe.

Backing: Weather advisories typically indicate poor outdoor conditions.

Qualifier: Should (moderate strength recommendation)

Rebuttal: Unless the forecast changes or we have proper gear.

Example 3

Text:

"Probably, the server crashed because too many users tried to log in at once."

Toulmin Breakdown:

Claim: The server crashed.

Grounds (Data): Too many users tried to log in at once.

Warrant: Excessive user traffic can overload and crash a server.

Backing: IT diagnostics show similar failure patterns during high traffic events.

Qualifier: Probably (indicating uncertainty)

Rebuttal: Unless there was a hardware failure or software bug unrelated to traffic.

Each example shows that much of the Toulmin model involves reconstructing implicit reasoning. The warrant is rarely stated and must be inferred, while the qualifier and rebuttal often rely on tone, context, or background knowledge. These compact cases illustrate both the utility and interpretive challenges of the model.

Appendix D – A Discussion About Tagging with Mode

In a prior discussion, the term "mode" was referenced as a classification tag within an argument-tagging system. This usage did not originate from the Toulmin model, where the relevant term is typically "qualifier", but from frameworks that draw on computational linguistics, discourse analysis, or pragmatics, where "mode" has a distinct technical usage.

Here is a clarification and reconciliation of that usage:

Distinguishing “Mode” from Toulmin’s “Qualifier”

In Toulmin’s framework, a qualifier indicates the degree of certainty or strength of a claim (e.g., “probably,” “necessarily,” “likely,” “possibly”).

In computational discourse analysis or semantic tagging systems, mode refers to the speaker’s attitude toward the likelihood, obligation, or desirability of a proposition. It encompasses multiple modalities:

Epistemic modality: likelihood or certainty (e.g., might, must, could)

Deontic modality: obligation or permission (e.g., should, may, ought)

Dynamic modality: ability or internal necessity (e.g., can, is able to)

So, mode in that system is a broader label, under which Toulmin’s qualifier is a subtype, specifically addressing epistemic confidence.

Example Reconstructions with “Mode” as a Tag

Below are two short argument examples with explicit “mode” tagging, in addition to Toulmin-style role tagging.

Example 1: Epistemic Mode

Text:

"She must be tired, because she barely slept last night."

Tags:

Claim: She must be tired.

Mode: Epistemic – must (high certainty)

Grounds (Data): She barely slept last night.

Warrant: People who don’t sleep tend to feel tired.

Qualifier (Toulmin): Must (strong inference)

Rebuttal (implied): Unless she had caffeine or adrenaline keeping her alert.

Example 2: Deontic Mode

Text:

"You should apologize, since your comment upset him."

Tags:

Claim: You should apologize.

Mode: Deontic – should (moral or normative obligation)

Grounds (Data): Your comment upset him.

Warrant: If one’s comment upsets another, an apology is warranted.

Backing: Common social norms about responsibility for emotional harm.

Qualifier: Should (moderate force; normative recommendation)

Rebuttal (implied): Unless the offense was unintended or trivial.

Summary of System Divergence

Toulmin uses “qualifier” to signal certainty about a claim.

Broader semantic or computational tagging systems use “mode” to indicate the modal force of a statement—whether epistemic (belief), deontic (duty), or dynamic (ability).

In practical tagging schemes, mode is sometimes treated as an independent tag layered on top of Toulmin roles, especially in linguistic or NLP applications.

If the goal is to analyze arguments linguistically (as in NLP or argument mining), mode will be treated as a surface-level semantic tag. If the aim is logical analysis (as in Toulmin), qualifier is the relevant role.