Reason: Semantics, Syntax, and Formal Systems Are Joined at the Hip

I try to understand formal systems with respect to the often made claim that they are only syntactic.

Author’s Preface

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about formal systems over the last few days, as part of my effort to understand reason. It occurred to me that standard depictions of formal systems may be somewhat lacking—and that the distinction between syntax and semantics, while useful in some contexts, is essentially ill-posed. It rests on a mix of Platonism, reification, and category mistakes. Of course, perhaps I’m wrong. On the other hand, perhaps I’m right.

To really get into this topic you have to come to grips with a lot of difficult technical material. It will be found in diverse disciplines as well. This is the 1000 foot view, and is overly simplified, and may well be mistated - there could be some hidden equivocation in my arguments for instance. However, this is my current take on the issues as a guerilla epistemologist.

1. Introduction to the Problem

This essay grew out of an attempt to understand how reason works. That led to questions about formal systems—things like logic, mathematics, programming languages, and the kinds of rule-based thinking used in philosophy and science. Many people claim that these systems are purely syntactic—that is, they’re just about manipulating symbols according to fixed rules, with no need for meaning. But that claim seems wrong.

When thinking about something as abstract as formal systems, it’s important to focus on what really matters. What does it mean to say something is “only syntactic”? Can symbols and rules really be separated from meaning? These are not just academic questions. They go straight to how we think, how we learn, and how we understand the world.

2. Syntax and Semantics: The Core Tension

At the center of this discussion is the split between two ideas: syntax (the structure or rules for combining symbols) and semantics (the meaning we attach to those symbols). In traditional thinking, syntax is supposed to be clean, precise, and separate from messy things like meaning or interpretation. It's treated as the skeleton, while semantics is the soft tissue.

But here’s the problem: when trying to describe a syntactic system—any system of rules for manipulating symbols—there’s no way to do it without using language. And language always carries meaning. Even when someone points to a supposedly “pure” syntactic rule, they explain it in words. They say what the rule does, how it applies, and what its purpose is. That’s all semantics.

In other words, syntax doesn’t float above meaning. It’s held up by it. The idea that one can have rules without any sense of what those rules are for or how they are used is just not how humans actually work with systems.

3. The Role of Description

Any time someone talks about a formal system—whether it’s a logical proof, a computer program, or a mathematical formula—they’re describing something. That description always involves meaning. If someone draws a diagram or writes a formula, they usually explain what it’s doing. “This is an addition symbol; this represents a variable,” and so on. That act of explanation is not syntax. It’s semantics. It’s interpretation. It’s language.

Even the bare act of identifying something as a “rule” or a “symbol” already brings meaning into the picture. So while it might be useful to say “syntax is just the structure,” that structure can’t be seen, talked about, or worked with without describing it. And description is always a matter of meaning.

4. Formal Systems as Linguistic Subsets

A formal system isn’t some alien creature apart from human thought. It’s just a special way of using language. It’s a constrained version of the kinds of things we already do when we speak or write. It uses a limited vocabulary and follows strict rules, but it’s still a kind of language.

This means syntax in a formal system is just a more tightly controlled kind of structure. It’s language on a diet. But it still needs human understanding to work. When a person builds or uses a formal system, they are making decisions, interpreting symbols, applying rules—and all of that is soaked in meaning. No one works with a formal system without thinking about what they’re doing, why it matters, or what the results mean.

5. Operators and Symbols: Inescapably Semantic

Let’s take the plus sign as an example. “+” isn’t just a scribble on a page. It stands for something—it means “add these two things together.” Even in abstract mathematics, where people talk about “uninterpreted symbols,” those symbols are still introduced, explained, and used in ways that require interpretation.

Even when someone says “this system doesn’t need meaning,” they have to describe what the system does and how to use it. That act of explaining is full of meaning. So while individual steps in a calculation might seem meaningless on their own, they only make sense when seen as part of a process with a goal. And that goal is always connected to human interpretation.

6. Railroad Diagrams and the Syntax Fallacy

Sometimes people try to represent syntactic rules with diagrams—like the “railroad track” diagrams used to show how computer languages are structured. These diagrams are supposed to be purely structural. But every element in the diagram has to be explained. What does this arrow mean? What does this label refer to?

If someone hands over a diagram without any explanation, it’s just lines and shapes. It only becomes useful when someone tells you what each part stands for. Once again, we see that even something designed to show “just syntax” depends entirely on meaning to be understood.

7. Description vs. Use of Formal Systems

It helps to separate two ideas: describing a system and using a system. Description always involves language and meaning. But what about use? Isn’t that just following the rules?

Not really. Even when someone follows the rules of a formal system, they’re doing so with a goal in mind. They interpret the results. They check whether what they’re doing makes sense. All of that involves meaning. So even though it might look like the system is being used “mechanically,” there’s a lot of interpretation happening behind the scenes.

8. Category Errors and Reification

Some confusion comes from treating syntax as if it were a thing—an object that exists on its own, like a chair or a tree. But syntax isn’t a thing. It’s a way of talking about how symbols are arranged and transformed. Treating it as a freestanding object is a mistake. It’s like confusing a recipe with a meal.

People sometimes turn abstract ideas into things in their minds. That’s called reification. It happens when we forget that a concept is just a tool for thinking and start treating it as if it exists independently. Syntax, when separated from semantics, is just such a concept. It looks solid, but it’s only meaningful because we’ve made it so.

9. Platonic Idealizations of Syntax

A lot of this thinking comes from an old habit in philosophy: imagining perfect forms that exist beyond the real world. In this view, syntax is one of those perfect forms—untouched by meaning, eternal, pure.

But this idea doesn’t hold up. Syntax isn’t floating out there in the void. It’s something people create, use, and adapt. It changes. It depends on how we define it, what rules we include, and what purposes we have in mind. Treating it as a timeless essence is a kind of fantasy—a leftover from philosophical traditions that imagined perfect truths beyond the messiness of real life.

10. Neuroscience and Cognitive Constraints

Brain research adds another layer to this. Studies of language and thought show that meaning and structure aren’t handled by separate compartments in the brain. When people read or hear language, the parts of the brain that process structure also help make sense of meaning, and vice versa.

The idea that syntax and semantics are handled in completely separate ways just doesn’t match what the brain is doing. Even when reading a simple sentence or solving a math problem, both kinds of processing light up and work together.

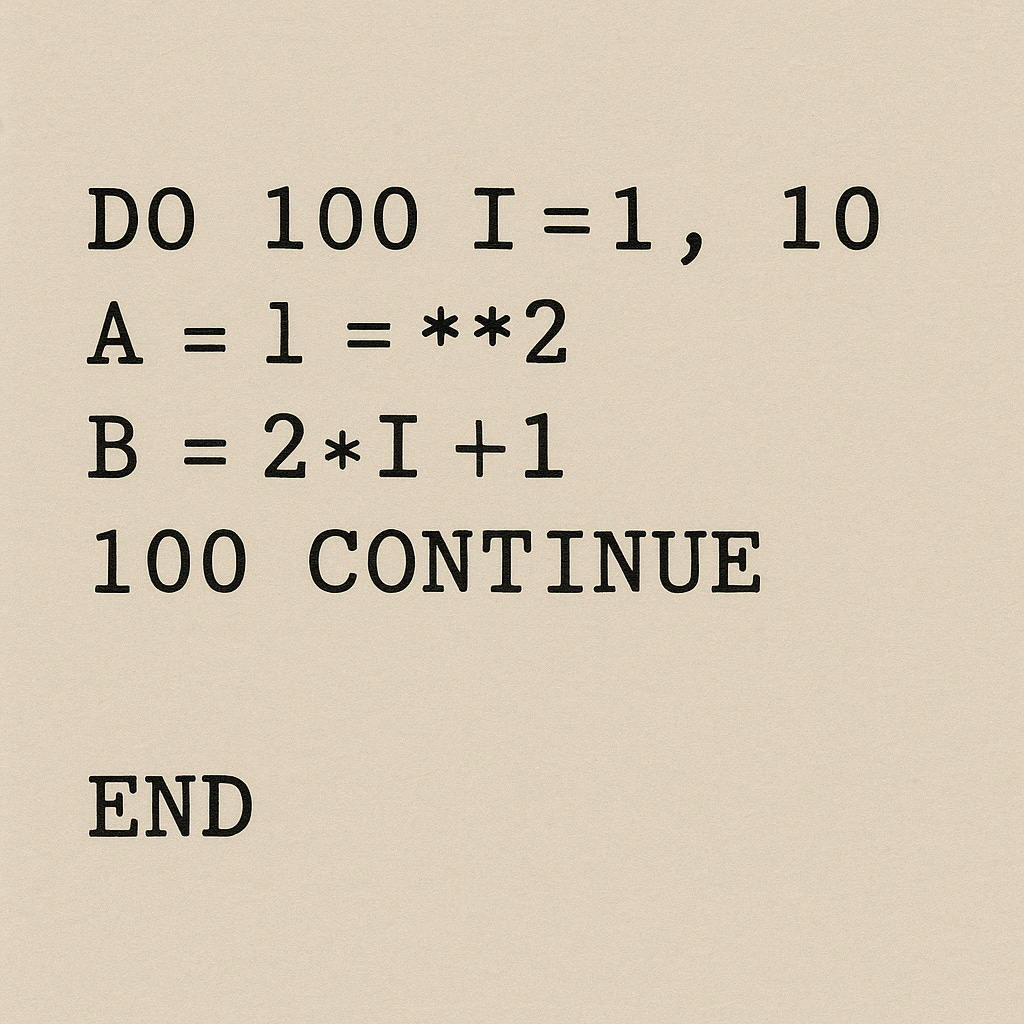

11. Program Writing, Debugging, and Understanding

Think about writing computer code. A machine might run the code blindly, following instructions exactly. But the person writing or debugging that code has to understand it. They have to think about what each part does, why it matters, and how it fits into the bigger picture.

That’s not just about rules. It’s about understanding loops, counters, conditions, and outcomes. It’s about knowing what a program is for. The machine doesn’t care. The human does. The meaning comes from the person, not the processor.

12. The Systemic Nature of Algorithmic Meaning

Even when a computer seems to operate on “just syntax,” the whole system—the hardware, the software, the code, the goals—is shaped by human intention. Nothing about a computer’s function makes sense without reference to human needs, meanings, and uses. The appearance of purely syntactic operation is just that—an appearance. Meaning is everywhere, even if it’s hidden behind the screen.

13. Searle’s Chinese Room Reconsidered

John Searle’s famous thought experiment—the Chinese Room—tried to show that machines can follow rules without understanding. But the example hides the fact that the rules, the inputs, and the outputs are all defined by humans. The system only “works” because people set it up and interpret its behavior.

What seems like pure syntax turns out, once again, to be shot through with meaning. Even when the machine “doesn’t understand,” the people around it do. The system is not just what happens inside the box—it’s the whole setup, including the context and the interpretation.

14. Pattern and Regularity: Semantic Hazards

It’s common to hear that syntax describes “patterns.” But the word “pattern” is vague. It can mean repetition, structure, motif, or even example. That kind of vagueness causes trouble.

A clearer way to think about syntax is this: it’s a system of rules for deciding which combinations of symbols are allowed and how those combinations can be changed. In many systems, these rules are strict and predictable. In others—like natural language or machine learning—the rules may allow options or probabilities.

The key point is that syntax, as most people use the term, really means a set of constraints for organizing and changing symbols. That’s much more precise than just saying “patterns.”

15. Determinism and Optionality in Syntax

In classical formal systems like arithmetic or logic, rules are fixed: the same input always gives the same result. But in systems designed to model human language, that’s not always true. Some rules are optional. Some are probabilistic. That means different outcomes are possible, depending on the context.

Still, these flexible systems are built on top of rules, and those rules must be described. And that brings us right back to meaning. Whether rigid or flexible, syntax doesn’t escape interpretation.

16. Responses to Common Objections

Some people argue that the distinction between syntax and semantics is still useful. That’s true, but it doesn’t make the separation real. Others say machines can run syntactic rules without understanding. Also true. But the rules, systems, and results all depend on human understanding. The machine doesn’t get to define what it’s doing.

Others try to build meaning from syntax using clever rules. But those rules only work because someone has already explained how to use them. And some insist that syntax is a pure mathematical object. But math itself needs meaning to be used or understood.

Even claims that the brain separates syntax and semantics are losing ground. Studies show that structure and meaning are processed together. The lines we draw between them are convenient for models—but not for minds.

17. The Hard Problems: Understanding, Meaning, and Consciousness

At the end of the day, meaning is part of the mystery of mind. How do we understand? What is understanding? How does a brain turn sound and symbols into sense? No one fully knows. But it’s clear that syntax alone isn’t enough.

Meaning, structure, and consciousness are tightly intertwined. They’re not separate boxes or clean categories. They are parts of a tangled web. And any theory that tries to split them too neatly is probably missing something essential.

Conclusion

Formal systems may look like they’re built from pure structure. But from the moment we describe them, use them, or explain them, we bring in meaning. Syntax doesn’t live on its own. It’s held up by semantics at every step. Trying to pull them apart is not just hard—it’s misleading. To understand reason, language, and thought, we have to see how tightly they are bound together. They’re not separate parts. They’re joined at the hip.