Reason: On the Frames We Cannot See – Cognitive Entrapment – Part I

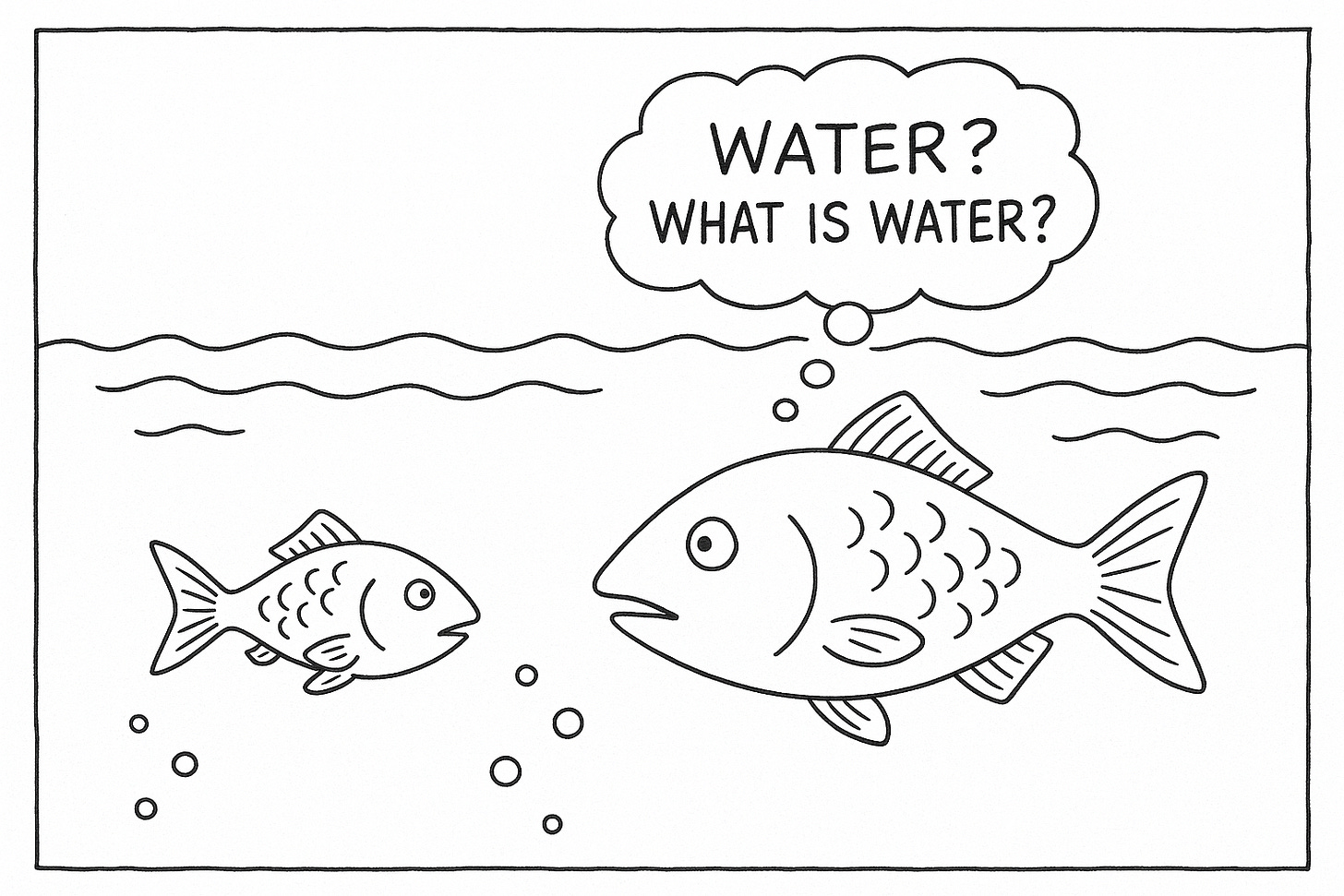

All thought lives inside a frame of language, values, and loyalties — and the hardest thing to see is the frame itself.

Introduction

Human reasoning never operates in a vacuum. It takes place within shared systems of language, doctrine, and method that both enable and constrain thought. These frameworks are reinforced not only by patterns of reasoning, specialized language, group norms, and institutional structures, but also by the deep fusion of ideas with emotions and values. This fusion gives beliefs their moral force, makes certain interpretations feel self-evident, and renders dissent costly in social and personal terms. The result is a form of cognitive entrapment in which people — scholars and laypersons alike — become unable to see beyond the boundaries of their own conceptual world, treating its assumptions as objective reality itself.

Discussion

Defining “Frame”

A frame is the invisible structure that shapes how something is seen, thought about, and discussed. It is made of shared assumptions, familiar examples, and built‑in values that guide attention toward certain facts and away from others. Frames work quietly in the background, so people usually don’t notice them — yet they define what seems obvious, what seems possible, and what seems out of bounds.

In this context, a frame is the set of ideas, assumptions, language, and values that shapes how a person or group understands the world. It works like an invisible outline: it decides what counts as a relevant fact, which questions seem worth asking, and what kinds of answers feel acceptable — often without anyone noticing it is there.

The term frame appears in multiple disciplines, each with its own emphasis:

Linguistics and Discourse Analysis – Refers to the way language choices set the context for interpretation. Closely tied to framing theory in communication studies.

Communication Studies and Media Studies – Describes how news and information are presented to influence how audiences interpret events.

Cognitive Science – Used in frame semantics (Charles Fillmore) to describe mental structures that organize knowledge and guide understanding of situations.

Psychology – In decision-making research, framing effects show how the same facts lead to different choices depending on how they are presented.

Sociology – In frame analysis (Erving Goffman), refers to the social structures and interpretive schemas people use to understand everyday situations.

Philosophy of Science – Sometimes used to describe conceptual frameworks or paradigms that guide scientific inquiry.

Artificial Intelligence – In early AI research, a “frame” was a structured representation of stereotypical situations used for reasoning.

In each case, the common thread is that a frame is not just a viewpoint but a structured context that shapes perception, interpretation, and judgment — often invisibly.

Speculation on Cognitive Entrapment

Cognitive (Reasoning Patterns)

Interaction: Emotional investment makes certain lines of reasoning feel inherently stronger, even when they are logically weak. This reduces the motivation to critically examine them.

Linguistic (Framing and Jargon)

Interaction: Value-laden terms — healthy, sustainable, rational — merge technical vocabulary with moral approval. The language itself conveys what ought to be believed, appealing both to cognition and to shared values.

Social (Group Norms and Identity)

Interaction: Emotional bonds within the group make intellectual conformity feel like loyalty. To dissent is not just to disagree — it is to risk social and emotional exile.

Institutional (Structures and Incentives)

Interaction: Institutions reward adherence to prevailing values and narratives. Emotional alignment with the institution’s mission strengthens compliance, making the rules feel morally right rather than merely strategic.

Emotional–Value (Feelings and Commitments)

Interaction: Serves as the binding agent across all other pillars. It gives cognitive positions moral weight, imbues linguistic frames with persuasive force, solidifies group belonging, and legitimizes institutional authority.

Reinforcement Loop

Values shape the language.

Language cues the “correct” reasoning.

Reasoning supports group solidarity.

Group solidarity is underwritten by emotional loyalty.

Institutions formalize and reward these alignments.

The cycle repeats, making the framework feel self-evident and deviations feel like moral failure.

The Overlooked Role of Emotion and Values in Cognitive Entrapment

What is commonly treated in mainstream psychology as “bias” is usually described in purely cognitive terms, as if the mind were a cool, detached reasoning machine occasionally thrown off course by quirks of logic. That framing is misleading. Much of what sustains cognitive entrapment is not just the structure of ideas but the emotional and value-laden charge bound up with them.

A few points stand out:

Values are woven into frameworks from the start.

What is treated as important to study, worth defending, or dangerous to question is never neutral. These value-choices become built into the very language and concepts of the field — “healthy diet,” “responsible journalism,” “good governance” — long before they are debated.Emotions reinforce loyalty to a framework.

Strong affect — pride, fear, hope, anger — ties individuals to their intellectual community. Dissent can trigger anxiety or anger not because the evidence is weak, but because it threatens the social-emotional bonds tied to belonging.Entrapment is self-reinforcing because it feels right.

People often experience alignment with their community’s framework as moral clarity or emotional truth. Even when evidence is thin, the internal coherence between beliefs, values, and emotional commitments can feel like certainty.Identity is not just cognitive but emotional.

Identity fusion is sustained by a mix of reasoning, shared values, and the emotional rewards of solidarity. Stepping outside the framework risks not just intellectual exile but emotional and moral dislocation.Interpretations are inseparable from value-laden framing.

This connects with what you attribute to “H.G.” — the claim that there are no “facts” in isolation from interpretation. Interpretation itself is colored by what the community values, fears, and aspires to. The “fact” is not a raw datum; it arrives already clothed in the framework’s moral and emotional dress.

This emotional–value dimension would sit alongside the cognitive, linguistic, social, and institutional dimensions in the discipline’s model, making the framework more complete. Without it, the analysis risks implying that entrapment is merely an error of thought, when in reality it is an embodied, affective commitment that is experienced as truth.

Nietzsche’s remark that “there are no facts, only interpretations” fits well with this, though in his case it was more of a philosophical provocation than a systematic model. He was pointing toward the impossibility of a view from nowhere — the idea that all perception and thought are filtered through perspective, which includes language, prior commitments, and, crucially, the emotional and valuative stance of the perceiver.

In that sense, the fusion of thought, emotion, and values — is not an add-on to bias theory but part of the core mechanism that makes cognitive entrapment durable. In many cases:

The emotional tone reinforces the plausibility of the interpretation.

The value commitments determine which “facts” get admitted as evidence.

The social-emotional rewards of belonging make reinterpretation costly.

These elements are woven into the framework itself, so that the boundary between “belief” and “value” dissolves. What appears to be a cognitive error from the outside is experienced from the inside as moral and emotional necessity.

That makes Nietzsche’s line, stripped of its aphoristic style, into a fairly straightforward description: facts arrive to us already in a frame, and the frame is made not just of concepts but also of the values and emotions that give them weight.

Any study of cognitive entrapment that begins and ends with “bias” is incomplete. Bias, as usually described, is treated as a flaw in reasoning, a distortion in the processing of information. But in lived experience, the reasoning process is never a purely detached exercise. Thought operates in constant interplay with emotion and value commitments.

Beliefs are rarely cold abstractions. They are carried on a current of feeling — loyalty, pride, fear, hope, resentment — and those feelings are themselves anchored in values, both explicit and unspoken. These values define what counts as important, urgent, admirable, or dangerous within a framework. They influence which “facts” are accepted, which questions are worth asking, and which interpretations seem self-evident.

It is here that Nietzsche’s observation — “there are no facts, only interpretations” — finds its enduring resonance. Facts do not come to us raw; they are admitted and understood through the lens of interpretation, and that interpretation is already bound to what the community values and feels to be true. From the inside, the convergence of belief, emotion, and value is experienced not as bias but as moral and emotional necessity. From the outside, the same convergence may appear as obstinacy, selective reasoning, or doctrinal closure.

This dimension cannot be treated as a secondary influence. It is a structural element in cognitive entrapment, on equal footing with the cognitive, linguistic, social, and institutional pillars. Without it, the account risks reducing entrenched thinking to a simple failure of logic, when in fact it is sustained by a much deeper integration of intellect, feeling, and value-laden identity.

Professional Training Doesn't Necessarily Make One Think Clearly

Professional training generally equips people to operate within a particular framework rather than to question the framework itself. It often rewards mastery of its accepted tools, language, and conventions, not the capacity to challenge or abandon them when they are inadequate. In many fields this produces technically proficient practitioners who may be adept at citing studies, or interpreting statistical outputs, yet who operate inside a self-reinforcing system of assumptions.

Clear thinking requires the ability to step outside those assumptions, examine their foundations, and recognize when the “rules of the game” themselves are flawed. Professional training does not necessarily cultivate this. Instead, it tends to encourage intellectual conformity, because certification, career advancement, and peer respect depend on staying within the discipline’s dominant paradigms.

In that sense, professional training can sometimes narrow thinking rather than broaden it—making people more skilled in their domain’s orthodox methods while less capable of fundamental critique. This is why it is possible for a field to be populated by highly trained experts who collectively fail to see its structural weaknesses.

Summary

This essay examines how human reasoning is shaped and constrained by the frames in which it operates. A frame is an invisible structure of language, assumptions, values, and loyalties that determines what counts as relevant evidence, which questions seem worth asking, and what kinds of answers feel acceptable. Frames both enable thought and make it difficult to think beyond their boundaries.

The discussion identifies five interacting pillars of cognitive entrapment: cognitive reasoning patterns, linguistic framing, social norms, institutional structures, and the emotional–value dimension. The fifth pillar binds the others, giving beliefs moral force, strengthening loyalty to group norms, and making dissent costly. These pillars form a reinforcement loop that renders the frame self-sustaining and self-validating.

The analysis emphasizes that cognitive entrapment is not simply the result of “bias” as described in psychology. It is a deeper integration of intellect, feeling, and value-laden identity that shapes interpretation before reasoning begins. Professional training, rather than freeing individuals from these constraints, often deepens them by cultivating expertise within a narrow, self-reinforcing framework.

The phenomenon is universal, occurring in scholarly, professional, and everyday contexts. Recognizing it is not an argument for abandoning truth claims but for cultivating meta-awareness of the interpretive scaffolding that guides thought. This awareness offers the possibility of loosening the grip of doctrinal closure and expanding the range of possible interpretations.

Readings

Annotated References

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

A foundational account of how scientific paradigms shape inquiry, resist change, and are eventually replaced. Relevant for understanding how entire communities operate within a shared frame until a shift forces reconsideration.Feyerabend, P. (1975). Against Method. Verso.

Argues that there is no single, universal scientific method and that rigid adherence to orthodoxy can stifle discovery. Offers examples of how methodological entrapment occurs.Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t Think of an Elephant!. Chelsea Green Publishing.

An accessible introduction to framing theory, showing how language shapes political and cultural interpretation. Useful for understanding the linguistic pillar of entrapment.Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink. Houghton Mifflin.

Classic work on how group pressures suppress dissent and critical evaluation. Directly relevant to the social pillar of entrapment.Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality. Anchor Books.

Explains how shared understandings of reality are built, maintained, and taken for granted. Offers insight into the institutional and cultural persistence of frames.Fillmore, C. J. (1982). “Frame Semantics.” In Linguistics in the Morning Calm (pp. 111–137). Hanshin Publishing Co.

Technical but important work describing how frames in language evoke structured knowledge and shape meaning. Useful for understanding how frames operate implicitly.Nickerson, R. S. (1998). “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220.

Comprehensive review of confirmation bias research, illustrating how prior beliefs influence interpretation and evidence evaluation.Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Harvard University Press.

Foundational sociological work on how people use interpretive schemas (frames) to make sense of events. Provides the broad sociological grounding for the concept.