Reason: Looking at Methods for Clear Argumentation

Arguments, arguments, arguments: I try to understand how to assess the worth of an argument, and improve the quality of my own ramblings. Good luck with that you say?

Table of Contents

Introduction

What Real Arguments Look Like

The Trouble with Natural Language

Modal Drift and Epistemic Blending

Reading an Argument: How to Dissect One

5.1 Identifying Key Claims

5.2 Unpacking Epistemic Modes

5.3 Detecting Rhetorical Contaminants

5.4 Assessing Evidence Structure

Crafting an Argument: How to Build One

6.1 Assembling Claims and Support

6.2 Structuring with Lines of Evidence

6.3 Using Connectives and Signposts

6.4 Avoiding Modal Confusion

Examples from Real Discourse

Missteps in Public Argument

Improving Argument Education

Summary: The Discipline of Clarity

Annotated Reading List (APA Format)

Author’s Preface:

Arguments are basically stories we tell ourselves, and others, in an attempt at persuasion. The topic under discussion is dissecting the arguments of others and improving our own arguments. Real arguments are quite rambling, discursive, rhetorical, I guess you'd say. It's very hard to disentangle what is being said in many cases. Very hard to distinguish verifiable facts on the ground from interpretations of those facts and predictions. Description and prediction get intermingled with other types of assertions, and that seems to be a common feature of most real-world discussions, essays, arguments, what have you. I do not exempt any of those I read from these criticisms, nor do I give myself a pass.

For decades, I have been reposting, aggregating links to articles of analysis and opinion. It goes without saying that the number of conflicting views on world events is astonishing—dismaying to me since I would really like to understand what is going on. Much of this dissension may be based upon reasoning which could, theoretically, be improved. Is there a solution to clearer reasoning? Can it result in more agreement? I do not know. I should mention that agreement—even consensus agreement—does not indicate truth. At the least, I would like to be able to dissect low quality reasoning more reliably and not just respond based upon tribal instincts.

We could probably do better, but we don't. I guess people would have to be explicitly taught how to do that. And as far as I know, teaching of composition doesn't have that as part of the curriculum, how to structure an argument properly. I freely admit it is hard, damn hard.

This monograph attempts to provide a foundation for evaluating and constructing real-world arguments without falling prey to the obfuscations of natural language, rhetorical sleight of hand, or intuitive bias. Argumentation is not a clean procedure but a difficult interpretive practice—yet it remains the central tool of reasoning in public life.

I had to use ChatGPT extensively here, since this material is way above my pay grade. I wish that I had been taught it as a young man. It goes way beyond my previous instruction. It seems that it will be a difficult skill to gain competency in.

Introduction

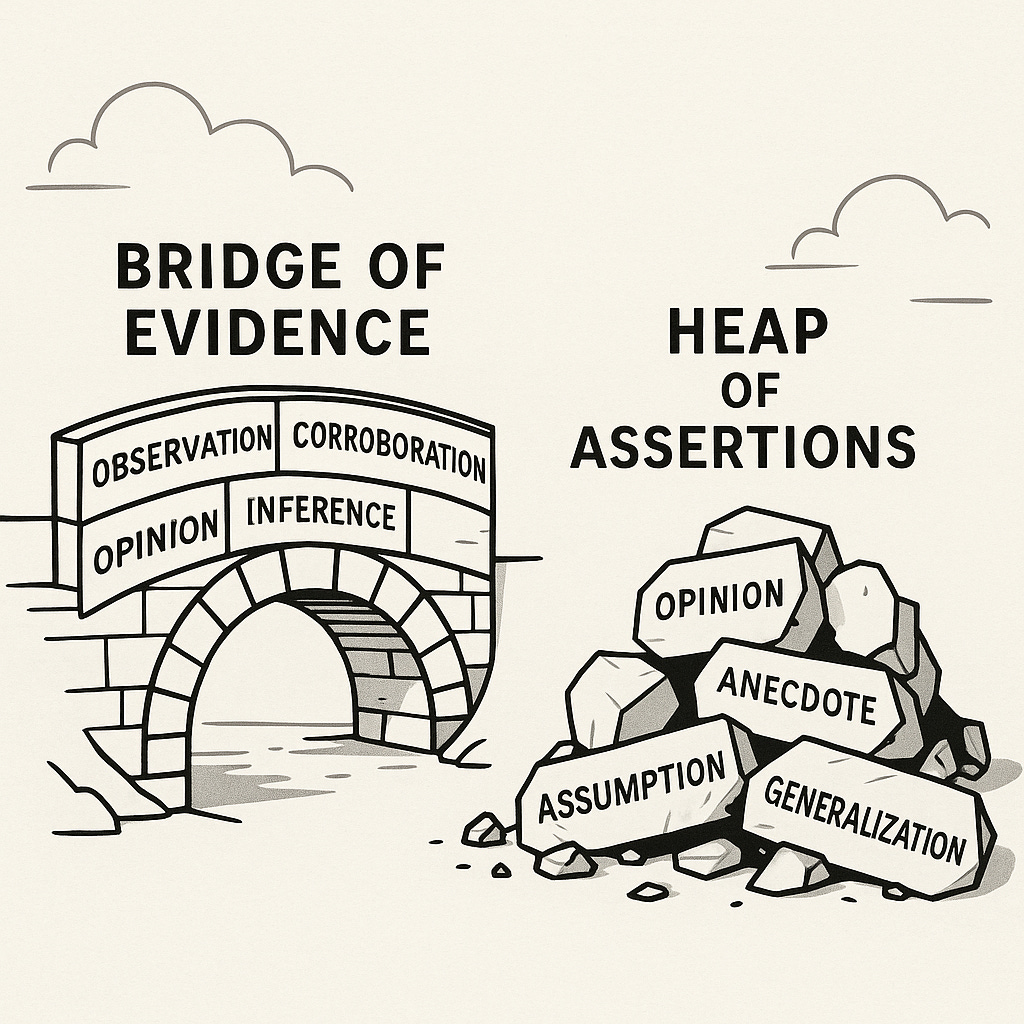

Much of contemporary discourse—whether political debate, academic writing, journalism, or casual commentary—fails not because of ill intent or lack of interest, but because of structural confusion. Arguments are frequently opaque, poorly organized, and rhetorically persuasive without being epistemically sound. They blend different types of claims—observations, interpretations, projections, and judgments—without clarifying the distinctions between them. As a result, even careful readers often struggle to determine what exactly is being asserted, on what basis, and with what degree of certainty.

This treatise investigates why real-world arguments are so often difficult to parse, easy to misread, and rarely disciplined in structure. It examines how natural language, cognitive bias, emotional resonance, and social context conspire to disguise the logical shape of arguments, even when they appear persuasive on the surface.

Unlike the clean, deductive exercises found in textbooks, real arguments do not begin with labeled premises or end with unmistakable conclusions. They are embedded in narrative, shaped by perspective, and informed by what the speaker already believes—or wants the audience to believe. Most arguments make multiple claims, not one; they involve overlapping forms of reasoning, not just deduction or induction. And they rarely signal when they shift from fact to speculation, or from description to value judgment.

The goal here is not to offer an idealized theory of argumentation, but to provide practical guidance for navigating and improving argument in real contexts. This includes:

How to recognize different epistemic modes (e.g., descriptive, predictive, evaluative),

How to identify rhetorical devices that obscure rather than clarify,

How to assess support through lines of evidence and cumulative reasoning,

How to distinguish between persuasive appearance and actual argumentative structure,

And how to understand the act of reasoning itself as situated, interpretive, and deeply human.

The capacity to reason clearly and argue well is not innate. It is a high-level skill, difficult to learn and seldom taught. But it can be learned. And in a world increasingly saturated with claims, counterclaims, and curated half-truths, it is more urgent than ever that it be cultivated.

Discussion

1. What Real Arguments Look Like

In structured logic, arguments are often presented in a clean form: premises stated clearly, a conclusion drawn deductively, and the whole affair packaged for evaluation by formal rules. This is known as syllogistic form, a classical structure that features two premises and a conclusion, such as:

All humans are mortal.

Socrates is a human.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This model is valuable in logic exercises and mathematical reasoning. But it is a poor reflection of how people actually argue in day-to-day life. Real arguments are messy. They are rarely explicitly labeled or neatly tiered. Instead, they resemble rough drafts written in a hurry—part explanation, part protest, part emotional appeal—delivered in a language evolved for storytelling rather than epistemic rigor.

Everyday Example: A Composite Statement

Take the example:

“The city hasn’t maintained its drainage systems, which is why we keep flooding every year, and now the mayor wants more taxes.”

This compact utterance contains at least three different modes of claim—a term that refers to the distinct ways in which a statement can function, depending on what kind of truth or judgment it expresses.

Observational Claim: “The city hasn’t maintained its drainage systems.”

– This is a statement about what is alleged to have happened. It purports to be a fact—a description of a verifiable condition. It could, in principle, be checked against maintenance records, photographs, or eyewitness reports.Causal Claim: “...which is why we keep flooding every year.”

– This introduces a causal inference: that the flooding is caused by the poor drainage. This type of claim involves more than observation—it interprets one event as the result of another. Determining the truth of this requires reasoning about mechanisms, alternatives, and other contributing factors (e.g., rainfall levels, urban development).Evaluative or Normative Claim: “...and now the mayor wants more taxes.”

– On its face, this is also observational (a political proposal is being reported). But the implication, especially when framed this way, is normative: it expresses disapproval or skepticism. The speaker appears to be saying it is unreasonable or unjust to ask for more taxes under these conditions. Normative claims are about what should or should not be the case, and they often rely on value assumptions.

Despite these different kinds of assertions, the sentence merges them into a seamless whole. There is no indication where one mode ends and another begins. Nor is there any signal as to how strongly the speaker believes each part, how confident they are in their data, or whether any of it is speculation.

This modal blending is typical of real discourse. Modal blending refers to the practice of mixing together different kinds of claims—factual, causal, speculative, normative—without clearly signaling which is which.

Additional Examples

Public Comment on Transportation Policy

“Traffic is a nightmare because the city council wasted money on bike lanes nobody uses.”

– Observation: “Traffic is a nightmare.” (subjective, but arguably empirical)

– Causal Inference: “...because the city council wasted money...”

– Evaluative Claim: “...bike lanes nobody uses.” (implies poor decision-making)

This is an argument embedded in a single sentence, but each part plays a different epistemic role. It weaves together sensory experience, political critique, and causality. A clearer structure might unpack this into parts:

What evidence exists that bike lanes caused more traffic congestion?

How was the spending decision made?

Are the bike lanes truly unused, or just perceived that way?

Media Headline

“Corporate greed fuels housing crisis.”

– This contains a blend of:

Causal claim: “fuels” implies a cause.

Interpretive framing: “corporate greed” is not an observable fact but a value-laden description of motivation.

Evaluative tone: The word “greed” carries moral condemnation.

This headline is persuasive, but analytically opaque. To assess the claim properly would require defining terms (what counts as “greed”?), separating economic data from moral judgment, and exploring alternative explanations for the housing crisis.

The Argument as a Tapestry

The metaphor of the argument as a tapestry is apt. Each thread—a description, a cause, a value judgment—adds to the picture. But without knowing which thread is which, or how securely it is anchored, the observer is left to interpret the whole as if it were unified. That creates the illusion of coherence, even when the underlying structure is weak or disjointed.

Formal logic teaches us how to analyze arguments as if they were mathematical. Real-world reasoning, however, is interpretive. It relies on intuition, framing, tone, prior belief, and rhetorical force. This means real arguments often function less like proofs and more like persuasive stories—constructed not to meet criteria of soundness, but to resonate with an audience.

Key Takeaways:

Real arguments are rarely formal and are usually a mixture of observations, inferences, and value judgments.

These types of claims—observational, causal, normative—should be distinguished when analyzing or constructing arguments.

Modal blending (mixing types of claims without clarifying them) is common and makes arguments harder to evaluate.

Readers and listeners must often untangle the different layers of an argument to assess its strength or coherence.

2. The Trouble with Natural Language

Natural language—the kind used in everyday conversation, journalism, essays, and argumentation—is the primary medium of human reasoning and persuasion. Unlike formal languages such as mathematics or symbolic logic, natural language is not optimized for clarity or precision. It is messy, ambiguous, full of nuance, and heavily dependent on context. While this makes it expressive and flexible, it also makes it unreliable when clarity is most needed—such as when evaluating or constructing an argument.

This section explores the key features that make natural language so difficult to work with in argumentation and illustrates each with multiple real-world examples.

2.1 Lexical Ambiguity

Definition: Lexical ambiguity occurs when a single word or phrase can have multiple meanings depending on how it is used. Words in natural language are not fixed definitions but flexible signs shaped by usage, tone, and context.

Examples:

“Justice”:

In one context, it may mean fairness ("We want justice for the victims"). In another, it refers to a legal outcome ("He was brought to justice"). These are not the same concept, though they are often conflated. When someone says “There was no justice,” it is not always clear whether they mean that legal procedures were ignored, or that the outcome feels morally wrong.“Responsibility”:

Consider the statement:

“The manager is responsible for the failure.”

This could mean:

The manager caused the failure (causal responsibility),

The manager should have prevented it (normative responsibility),

The manager is the one being held accountable, regardless of actual cause (administrative responsibility).

These distinctions are rarely clarified in ordinary speech, yet each implies a different standard of judgment and remedy.

“Free speech”:

The term may mean:Legal protection from government censorship (constitutional),

Social tolerance for divergent views (cultural),

Unrestricted ability to offend without consequence (extremist interpretation).

When people argue about “free speech,” they often argue past each other because they are using different definitions.

2.2 Contextual Dependency

Definition: Natural language statements often rely on context—shared knowledge, social cues, recent events—for their meaning. Without this background, meaning becomes opaque or misleading.

Examples:

“They knew what they were doing.”

This sentence could be read as:An accusation of premeditation,

A compliment for strategic thinking,

A sarcastic condemnation.

The phrase alone is inert; its force depends entirely on tone, situation, and prior information.

“You always do this.”

In a domestic argument, this may refer to a pattern of behavior. But to an outside reader or listener, the referent (“this”) is unclear. The phrase depends on a shared past that is not accessible in the text itself.“It’s too late now.”

This may imply regret, inevitability, closure, or warning. The specific meaning depends on the broader conversation. In isolation, the phrase is almost meaningless.

Contextual dependency creates interpretive opacity—a situation where a sentence cannot be fairly evaluated unless the reader has insider access to its context.

2.3 Implicit Logic

Definition: Much of the reasoning in natural language is not stated outright. Arguments often depend on unstated premises—assumptions that are left for the listener to supply. This is efficient but dangerous, as different people fill in different assumptions.

Examples:

“She lied. So she can’t be trusted.”

Unstated premise: People who lie once are generally untrustworthy.

But is this always true? Context matters. Was it a serious lie? Was it part of a pattern? Without stating the premise, the argument relies on a generalization that may or may not be valid.“The policy failed, so the minister should resign.”

The logical connection between policy failure and resignation assumes:The minister is responsible for the policy,

Resignation is the appropriate response to failure.

Neither premise is stated. If the minister inherited the policy, or if resignation would create worse instability, the conclusion may not follow.

“He’s rich, so he must be smart.”

This leap involves the hidden premise that wealth is earned through intelligence—an assumption that is sociologically loaded and often unexamined.

Implicit logic allows arguments to appear valid while hiding the very assumptions that ought to be questioned.

2.4 Rhetorical Coloration

Definition: Rhetorical coloration refers to the way that tone, metaphor, irony, and word choice shape how a statement is received, often steering interpretation more than content does. While these devices can make arguments vivid, they also obscure reasoning.

Examples:

Irony:

“Well, that was a brilliant idea.”

Literally a compliment, but in context, likely a rebuke. This reversal makes it hard to analyze the actual claim—because the meaning lies not in the words but in the delivery.

Sarcasm:

“Oh sure, the government really cares about poor people.”

Again, the literal text says one thing, the tone implies the opposite. An argument embedded in sarcasm is hard to rebut because its claims are submerged.

Metaphor:

“The economy is a sinking ship.”

This is emotionally evocative, but imprecise. Is the economy doomed? Poorly managed? Under assault? Metaphors carry connotations but not definitions. They persuade through imagery, not evidence.

Loaded Language:

“The bureaucrats imposed yet another tax.”

The term “bureaucrats” carries a pejorative tone. “Imposed” suggests force. The sentence primes the reader to adopt a hostile stance even before the facts are evaluated.

Rhetorical coloration often functions as a form of argumentative camouflage. It masks the logical form of the claim by wrapping it in emotional texture.

Reconstructing the Skeleton

The goal of analyzing natural language arguments is to reconstruct the logical skeleton—the bare structure of claim, evidence, reasoning, and conclusion that may be hidden within the prose. This requires asking:

What is the claim being made?

What reasons are offered, explicitly or implicitly?

What assumptions does the argument depend on?

What kind of statement is this—fact, judgment, forecast?

Is the language shaping the perception more than the evidence?

This reconstruction is not mechanical. It is interpretive and often contentious. Two readers may extract different skeletons from the same text depending on their background, expectations, or biases. But without this effort, arguments cannot be evaluated fairly or clearly.

Illustrative Example: Editorial Excerpt

“Once again, City Hall has proven that incompetence knows no bounds. After ignoring years of warnings from urban planners, they’ve rolled out a housing policy so shortsighted it could’ve been written by a landlord with a grudge. The result? Skyrocketing rents, evictions, and families living in vans.”

Deconstruction:

Claim: The city’s housing policy is harmful and poorly conceived.

Evidence (implicit): Warnings were ignored; consequences have followed.

Rhetorical elements: “incompetence knows no bounds” (hyperbole), “landlord with a grudge” (metaphor), “once again” (implies a pattern).

Unstated premise: Urban planners had viable alternatives; policy authors were either ignorant or malicious.

Evaluative tone: Highly negative, loaded with insinuation and blame.

In order to analyze this argument, one would need to extract the claims about policy and outcomes, strip away the rhetorical heat, and identify what specific evidence supports the implied causal link between decisions and social consequences.

Conclusion

Natural language is inherently unsuited to precise argument without conscious effort. Its power lies in its richness, but this richness comes at the cost of clarity. For argumentation, this means:

Definitions must be watched.

Context must be inferred.

Logic must be reconstructed.

Rhetoric must be disentangled.

Without such vigilance, persuasion can masquerade as proof, and assumptions can be mistaken for facts.

The next section will explore how modal drift and epistemic blending further complicate reasoning in natural discourse, showing how different types of claims—about what is, what will be, and what ought to be—are often mingled indistinguishably.

3. Modal Drift and Epistemic Blending

Natural language arguments often move fluidly between different types of statements—statements about what has happened, what will happen, what might have happened, what should happen, and why something happened. These modes of discourse reflect different kinds of reasoning, but in real-world speech and writing, they are rarely marked or separated. The result is a slippage between forms that creates confusion, bias, and often, persuasive force without analytical clarity.

This phenomenon is referred to here as modal drift and epistemic blending.

3.1 Definitions of Key Terms

Modal drift refers to the unmarked transition between different modes of reasoning or speech within the same argument or even the same sentence. These modes include:

Descriptive (what is),

Predictive (what will be),

Counterfactual (what could have been),

Normative (what should be),

Causal (what caused what),

Evaluative (how good or bad something is).

Epistemic blending refers to the mixing of claims that differ in their epistemic status, meaning the kind of certainty or justification that supports them. Some claims are empirical (verifiable by observation), others are probabilistic (based on models or trends), and still others are moral or normative (based on values or preferences). When these are blended without clarification, it becomes difficult to tell which part of an argument is fact, which is conjecture, and which is judgment.

3.2 Example of Modal Drift

“The emergency services didn’t arrive for over an hour—clearly, they don’t care about poorer neighborhoods.”

This sentence shifts through at least three modes:

Descriptive: “Emergency services didn’t arrive for over an hour.”

– A factual claim (possibly verifiable through records or reports).Causal/Interpretive: “—clearly,”

– Implies a cause-effect relationship or an inference from fact to motive.Normative/Judgmental: “they don’t care about poorer neighborhoods.”

– A moral or evaluative claim about institutional priorities or injustice.

The sentence moves from observation to interpretation to accusation without any cue that these are different types of statements. The transition is made to appear seamless, which encourages the listener to accept the judgment as if it were part of the fact.

3.3 Real-World Examples

Example 1: Policy Commentary

“The government failed to regulate banks in time. That’s why the economy collapsed. They knew this would happen and let it anyway—they’re in the pocket of the financial industry.”

Factual: "The government failed to regulate..." (descriptive)

Causal: "That’s why the economy collapsed." (causal inference)

Speculative: "They knew this would happen..." (claim of foreknowledge)

Normative/Evaluative: "They’re in the pocket..." (moral accusation)

Here, modal drift builds a powerful narrative by gradually transforming a historical observation into a moral indictment. Each step is rhetorically forceful but analytically unstable unless each link is separately justified.

Example 2: Medical Policy Argument

“The vaccine hasn’t been studied long enough. Long-term effects are unknown. For all we know, it could cause infertility. Mandating it is unethical.”

Descriptive: "Hasn’t been studied long enough" (empirical claim)

Uncertainty/Speculation: "Long-term effects are unknown" (open-ended but true)

Counterfactual/Hypothetical: "It could cause infertility" (conjectural)

Normative: "Mandating it is unethical" (value-based)

The epistemic status of each statement is distinct, but they are presented as a coherent block. The speculative element is rhetorically treated as equivalent to the factual observation. The conclusion is a value judgment that appears to rest on empirical uncertainty, but without clarifying how strong that uncertainty is or how it should weigh against competing values (e.g., public health).

3.4 Why Modal Drift Matters

Failing to distinguish between different modes of assertion introduces several problems:

Misreading: A listener may interpret a judgment as a fact, or a speculation as a causal explanation.

Overreach: An author may sneak in a strong conclusion based on weak or uncertain premises.

Bias confirmation: Readers may accept a blended narrative because it fits their worldview, not because the logic holds.

Immunization from critique: If challenged, a speaker can retreat to a weaker interpretation of their statement (“I was just raising a possibility”), while having implied a much stronger one.

3.5 Common Forms of Modal Blending

1. Observation + Inference + Accusation

“He missed three meetings. He obviously doesn’t care about the project.”

Observation: Missing meetings.

Inference: Implies lack of commitment.

Accusation: Presents a motive as fact.

A fairer version would isolate the modes: “He missed three meetings. That might suggest a lack of commitment, but we don’t know why.”

2. Trend + Prediction + Moral Conclusion

“Crime has been rising for years. At this rate, no neighborhood will be safe. Politicians have failed us completely.”

Trend: Descriptive data.

Projection: Predictive logic.

Moral condemnation: Normative assessment.

Blending these allows the writer to use fear to justify a broad claim of failure without specifying what failure occurred, by whom, or by what standard.

3. Fact + Hypothetical + Judgment

“He had a history of aggression. If he had been properly monitored, the attack could have been prevented. The system failed.”

Factual background

Counterfactual reasoning (what might have happened)

Judgmental conclusion

This is common in post-crisis commentary. The argument feels persuasive because it creates a plausible alternate world, then condemns reality for not matching it. But counterfactuals are notoriously hard to prove.

3.6 How to Recognize and Clarify Modes

To evaluate such arguments:

Identify the types of claims:

What is being observed?

What is being guessed or speculated?

What is being asserted as causal?

What is recommended or condemned?

Ask what kind of evidence would support each part:

Observations: empirical verification.

Predictions: models, past patterns.

Causal claims: mechanisms, alternative explanations ruled out.

Value judgments: reference to shared standards or ethical frameworks.

Look for abrupt transitions:

Does a factual tone suddenly give way to outrage or praise?

Are assumptions smuggled in under cover of descriptive language?

Is something possible being treated as something actual?

3.7 Summary of Problems Created by Modal Drift and Blending

Makes weak claims seem strong through proximity to strong ones.

Encourages judgment before analysis.

Obscures what kind of justification is being used for each claim.

Provides rhetorical power at the expense of logical integrity.

Conclusion

Modal drift and epistemic blending are not rare errors. They are built-in tendencies of human language and communication. They allow speakers and writers to create persuasive, emotionally compelling arguments—without having to meet the standards of sound reasoning or careful justification. The burden, then, falls on the careful reader or listener to separate out the strands of description, prediction, speculation, and judgment. That separation is the first step toward clear understanding—and better argument.

In the next section, the focus turns to strategies for reading arguments closely: how to identify what is being claimed, how to distinguish assumptions from conclusions, and how to track shifts in mode that may be subtle but significant.

4. Reading an Argument: How to Dissect One (Expanded)

Arguments in real life rarely present themselves in textbook form. They are not simple chains of premises leading neatly to a single conclusion. Instead, most arguments—especially those found in essays, opinion pieces, public commentary, or conversation—present a cluster of claims, woven together by assumptions, implications, side-comments, rhetorical cues, and often emotional appeals. The task of reading an argument well involves untangling this cluster, identifying its key parts, and reconstructing its logic in a way that allows it to be examined critically.

This section outlines four interlocking strategies for dissecting an argument: identifying key claims, unpacking epistemic modes, detecting rhetorical contaminants, and assessing the structure of the evidence.

4.1 Identifying Key Claims

Key claims are the central assertions or points around which the argument is organized. However, most arguments make multiple claims, often of different types and strengths. These include:

Explicit claims: Stated outright.

Implied claims: Left for the reader to infer.

Assumed claims: Taken for granted as background or obvious.

Suggested but unstated ideas: Hinted at through tone or association.

A careful reading begins by extracting and paraphrasing these. One effective approach is to mentally summarize the text in the form:

“This writer is asserting that X, implying Y, based on Z.”

Example 1: Editorial on Urban Policy

“Instead of investing in infrastructure, the city poured millions into unnecessary beautification projects. Now potholes litter the streets, buses run late, and working-class neighborhoods are falling apart. City Hall needs a wake-up call.”

Paraphrased dissection:

Explicit claim: The city prioritized beautification over infrastructure.

Implied claim: Poor infrastructure is harming basic services.

Assumed claim: Infrastructure should be a higher priority than aesthetics.

Value judgment: The city government is negligent or out of touch.

Notice that no single sentence says “this is the argument,” and no clear premise-conclusion form is visible. The reader must extract it.

Example 2: Online Commentary on Education

“Kids aren’t learning anything useful in school anymore. It’s all about feelings and identity. No wonder test scores are dropping.”

Explicit claim: Schools are no longer teaching useful material.

Implied causal claim: A curriculum shift toward emotional or identity topics is causing lower academic performance.

Unstated assumption: Traditional subjects (math, science, etc.) are being displaced.

Normative claim: Schools ought to focus on academically “useful” content.

An effective analysis resists the temptation to agree or disagree at first and focuses instead on what is being claimed and how the claims relate to each other.

4.2 Unpacking Epistemic Modes

Every claim has a mode—a type of assertion with its own evidentiary requirements. Understanding what kind of statement is being made helps the reader determine what kind of evidence or reasoning is appropriate. These modes include:

Descriptive: Statements about what is.

“The bridge collapsed.” (Can be verified by observation or record.)

Predictive: Statements about what will happen.

“The bridge will collapse if not repaired.” (Requires modeling or trend analysis.)

Normative: Statements about what should be.

“The city should fix the bridge.” (Depends on values or priorities.)

Counterfactual: Statements about what might have happened.

“If the city had acted, the bridge wouldn’t have collapsed.” (Speculative; requires imagining alternative scenarios.)

Evaluative: Judgments about how good or bad something is.

“This was a failure of leadership.” (Depends on criteria for what leadership ought to accomplish.)

Example: Policy Letter

“The flooding last year destroyed several homes. If officials had responded to earlier warnings, this disaster might have been avoided. Their delay was unacceptable.”

Modes:

Descriptive: Homes were destroyed.

Counterfactual: Warnings were ignored; disaster might have been avoided.

Evaluative: Delay was unacceptable.

Failing to identify these modes leads to confusion. For example, taking a counterfactual as if it were a proven causal claim can lead to unwarranted conclusions.

4.3 Detecting Rhetorical Contaminants

Arguments are often shaped by rhetorical devices—figures of speech, emotional tones, or stylistic choices that influence how a claim is received, but do not clarify its logical content. These include:

Metaphors: Analogies that evoke imagery rather than detail.

“The tax system is a leaky bucket.”

(What precisely is being claimed? Is money lost? Is the system unfair? The metaphor invites interpretation without clarifying.)

Pejoratives: Loaded terms that signal disapproval without reasoning.

“The nanny state wants to control everything.”

(“Nanny state” is a disparaging metaphor that bypasses discussion of policy specifics.)

Irony/Sarcasm: Comments that mean the opposite of what they say.

“Oh, brilliant policy—now let’s tax breathing too.”

The real claim (opposition to the policy) is disguised beneath tone, requiring interpretive effort to recover.

A fair reading involves mentally stripping these elements out:

Replace metaphors with literal restatements.

Rephrase sarcasm into direct statements.

Discard pejorative tone to isolate the core assertion.

This does not mean ignoring rhetorical tone—it may reflect the author’s intent or appeal strategy—but clarity demands reconstructing the actual propositional content underneath the rhetorical surface.

4.4 Assessing Evidence Structure

An argument’s persuasiveness often depends not only on its claims, but on how those claims are supported. Evidence structures vary in complexity and strength:

1. Atomic Evidence

A single, isolated piece of support.

“Last week’s blackout lasted 12 hours.”

– Useful, but limited. On its own, it doesn’t justify broad claims about energy policy.

2. Lines of Evidence

Multiple independent observations or sources pointing toward the same conclusion.

“The blackout lasted 12 hours. Maintenance logs show overdue repairs. Consumer complaints about outages have tripled. Regulators have issued warnings.”

– These form parallel supports for the claim that the electrical grid is poorly managed.

Each line may be weak individually but becomes stronger when they converge.

3. Cumulative Argument

A set of weaker or circumstantial points that build a plausible case through accumulation.

“No one has seen the mayor in weeks, city press conferences have been canceled, and rumors of illness are circulating.”

– None of these individually proves that the mayor is ill, but together they suggest it is plausible.

A cumulative argument relies on weight, not on definitive proof.

Practical Questions for Evaluating Evidence:

Is the evidence relevant?

Does it directly support the claim or merely create atmosphere?Is it sufficient?

Even if true, is it enough to justify the claim being made?Is it independently corroborated?

Are multiple, unrelated sources making the same observation, or are they echoing one another?

Example: Environmental Report

Claim: “The lake is being poisoned by agricultural runoff.”

Evidence:

Water quality samples show high nitrate levels. (Atomic evidence)

Satellite images show expanding algal blooms over time. (Line of evidence)

Residents report increased fish deaths and murky water. (Cumulative/experiential)

A careful reader assesses whether these different forms of evidence truly support the same conclusion, or if they point to different causes.

Conclusion

Reading an argument is not about taking statements at face value. It requires:

Parsing what is claimed, implied, and assumed.

Identifying the mode of each assertion to assess its evidentiary needs.

Removing rhetorical clutter to see the underlying reasoning.

Understanding the structure of the evidence and how it is meant to function.

Arguments, especially in public discourse, are rarely linear. They present constellations of claims, not single stars. The skilled reader reconstructs the logic beneath the narrative—and can then fairly judge its strength.

In the next section, the focus turns to how arguments are crafted—how one can move from raw opinion or experience to a coherent, organized, persuasive presentation that respects these principles.

5. Crafting an Argument: How to Build One

While reading an argument requires dissection and interpretive reconstruction, crafting an argument is a generative process. It begins with a claim—something the speaker or writer wants to establish—and proceeds through the careful selection of supporting material, attention to logical coherence, and rhetorical clarity. A well-formed argument is not just a collection of facts or opinions; it is an organized structure of claims and evidence arranged in such a way that the intended conclusion becomes credible, persuasive, and resilient to challenge.

This section outlines four principles for constructing clear, coherent arguments: assembling claims and support, structuring with lines of evidence, using connectives and signposts, and avoiding modal confusion. Each principle is illustrated with detailed examples to show how arguments can be strengthened through thoughtful composition.

5.1 Assembling Claims and Support

Begin with a central assertion—the claim to be defended or explored. This may be a factual claim, a causal relationship, a judgment, or a recommendation. Then ask three guiding questions:

What supports this claim?

What assumptions are embedded in the claim or its support?

What objections might reasonably be raised?

Crucially, a strong argument distinguishes between:

Observation: What is directly verifiable.

Interpretation: What is inferred or concluded.

Judgment: What is endorsed or condemned.

Example: Environmental Claim

Claim: “The city’s air quality policy is ineffective.”

Support 1 (Observation): Recent air quality index (AQI) readings remain above safe thresholds.

Support 2 (Interpretation): Despite regulations, major emitters have not changed practices.

Support 3 (Judgment): Residents continue to suffer health consequences, suggesting policy failure in its intended effect.

Embedded assumptions:

That AQI thresholds are valid indicators of success.

That regulations should yield measurable results in a short time.

That compliance is a fair proxy for effectiveness.

Possible objections:

Air quality may be affected by factors outside municipal control (e.g., regional wildfires).

The policy may be new and outcomes delayed.

A transparent argument acknowledges these assumptions and anticipates objections, making it more robust.

5.2 Structuring with Lines of Evidence

Rather than relying on a single piece of support, effective argument construction employs multiple, independent lines of evidence—each providing a different angle or form of confirmation. This structure:

Strengthens plausibility,

Reduces vulnerability to disproof of any one claim,

Allows for varied types of reasoning (statistical, experiential, comparative).

Example: Claim — “The transit system is unreliable.”

Line of Evidence 1: Delay statistics from the past three years show a consistent 18% of buses arriving more than 10 minutes late. (Quantitative evidence)

Line of Evidence 2: A long-running community forum documents rider complaints about erratic schedules, missed stops, and unhelpful real-time updates. (Aggregated anecdotal evidence)

Line of Evidence 3: The city ranks below national average on the Transportation Reliability Index compared to cities of similar size. (Comparative statistical evidence)

Together, these lines support the claim not by mere repetition but through diversity of source and form:

Measurable data,

Subjective reports,

External benchmarks.

Even if one line were challenged (e.g., if delay data were incomplete), the others remain, giving the argument resilience through redundancy.

5.3 Using Connectives and Signposts

In spoken and written argument, connectives and signposts perform critical functions: they link claims to reasons, contrast competing views, introduce concessions, or clarify implications. These are not ornamental. They constitute the logic markers of natural language argumentation.

Common connectives include:

Causal: because, since, due to, as a result

Inferential: therefore, thus, so, it follows that

Contrasting: however, but, nevertheless, yet

Clarifying: in other words, that is, to put it differently

Concessive: although, even though, despite, while it is true that

Example A (with connectives):

“Bus delays have increased every quarter for two years. Therefore, the system cannot be described as improving. However, officials argue that new data tracking measures are still being implemented. Even so, the public’s experience continues to deteriorate.”

Without these markers, the relationships between statements would be ambiguous. The reader would be left guessing whether the writer is reinforcing, contradicting, or qualifying their claims.

Example B (without connectives):

“Bus delays have increased. The system cannot be described as improving. Officials argue new data tracking measures are being implemented. The public’s experience continues to deteriorate.”

Here, the structure is harder to follow. Is the second sentence a conclusion? A restatement? Is the third sentence an objection? A concession?

Arguments benefit greatly from clear, deliberate connective language. Flow can coexist with clarity, but clarity should not be sacrificed for stylistic smoothness.

5.4 Avoiding Modal Confusion

Modal confusion arises when different types of claims—descriptive, inferential, evaluative—are presented without clarifying their certainty or basis. This leads to misinterpretation, overstatement, or inappropriate confidence in what is really only conjecture.

To avoid this, signal the strength and kind of the claim. Use modal qualifiers to calibrate what is being said.

Modal Examples:

Suggests: Indicates a tentative inference.

“The data suggests a correlation between air pollution and asthma rates.”

May indicate: Indicates weak or circumstantial evidence.

“Rising absenteeism may indicate dissatisfaction with working conditions.”

Must / Clearly: Indicates strong inference or apparent certainty.

“If these numbers are accurate, the company must be underreporting losses.”

Overuse of strong modalities like “clearly,” “undeniably,” or “obviously” often signals rhetorical overreach, especially if the evidence is not overwhelming. Readers are sensitive to tonal overstatement; arguments gain credibility by matching claim strength to evidence strength.

Contrast Example:

Weak version:

“The mayor’s absence from the ceremony clearly shows she doesn’t care about veterans.”

– This asserts motive with unjustified certainty.

Improved version:

“The mayor’s absence may have been interpreted by some as indifference, though no official explanation was provided.”

– This acknowledges perception, without asserting a hidden motive as fact.

Additional Illustration: Assembling a Complex Argument

Claim: “The school’s remote learning program is not serving students effectively.”

Line 1 (Observation): Attendance rates have dropped by 23% since online classes began.

Line 2 (Anecdote): Parents report that children are disengaged and falling behind.

Line 3 (Comparative): Test scores in math and reading have declined relative to regional averages.

Signposting:

“Although digital platforms have improved accessibility, the outcomes suggest diminishing engagement and performance.”

“For example, data from district reports show...”

“This supports the view that remote learning, while necessary in emergencies, requires significant redesign to be viable long-term.”

Modal discipline:

“May reflect” rather than “proves.”

“Appears to be” rather than “is.”

“Suggests a trend” rather than “shows a failure.”

Conclusion

Crafting a strong argument involves more than expressing an opinion or listing facts. It requires:

Selecting and articulating a clear claim,

Supporting it with multiple forms of evidence,

Making logical relationships explicit through connective language,

And maintaining discipline in how the nature and strength of each claim is presented.

The best arguments are not those that overwhelm with volume, but those that are clear, structured, and appropriately calibrated—so that they invite understanding, withstand scrutiny, and do not overreach their evidence.

6. Examples from Real Discourse

Arguments in public discourse—whether in newspapers, blogs, political speeches, or public commentary—rarely present themselves in carefully labeled parts. Instead, they arrive as blended performances: combinations of factual claims, judgments, predictions, insinuations, and calls to action, often delivered in emotionally loaded or rhetorically charged language.

To understand how such arguments work—and how they sometimes fail—it is essential to practice parsing real-world examples. This means identifying the type of each claim (factual, interpretive, predictive, normative, etc.), understanding the evidentiary basis for each, and recognizing where distinct claims are blended without clarification.

6.1 Breakdown of a Hypothetical Newspaper Column

Headline:

“Government Incompetence Caused the Housing Crisis”

This is a conclusion that depends on several distinct kinds of claim. In many real columns, these are not laid out in formal order, nor are they labeled. Instead, they are distributed across the piece in narrative form. Below is a detailed breakdown of the types of claims typically embedded in such discourse.

A. Historical Data on Housing Starts (Empirical Claim)

“Housing construction peaked in 2007 and then fell by more than 40% over the next five years.”

This is a descriptive, empirical statement. It reports on observable facts that can, in principle, be verified by public records.

Mode: Descriptive

Evidentiary base: Official housing statistics

Potential pitfalls: Data selection bias, absence of context (e.g., economic conditions, interest rates)

While such data provides grounding, it does not explain why the housing crisis occurred—only what happened. Alone, it cannot establish causality.

B. Analysis of Regulation Effects (Interpretive Claim)

“Zoning laws and overregulation made it virtually impossible to increase housing supply in major urban centers.”

This is interpretive—it connects policy to consequences. The claim implies a causal relationship: that specific government actions produced a limitation on housing availability.

Mode: Causal inference

Evidentiary base: Policy documents, historical trends, economic models

Assumptions: That regulation was the primary limiting factor, rather than labor shortages, construction costs, or NIMBYism (local opposition to development)

This type of claim requires reasoned argument and support—it must establish not just correlation but mechanism.

C. Statements like “They Ignored the Warnings” (Evaluative and Implied Counterfactual)

“Economists had warned about speculative bubbles in 2006, but officials did nothing.”

This is both evaluative and counterfactual.

Evaluative: Implying negligence or dereliction of duty

Counterfactual: Suggesting that if officials had acted, the crisis might have been averted

Such claims do not assert fact directly, but rather imply what should have happened, using what didn’t happen as evidence of failure.

Mode: Interpretive and normative

Evidence required: Documentation of warnings, records of inaction, plausible interventions that were available and ignored

Ambiguity: What counts as “doing something”? How actionable were the warnings?

Without clarity, this can turn into post hoc rationalization—the assumption that because something bad happened, those in power must have failed.

D. Predictions of Market Collapse (Speculative Claim)

“If these policies continue, we’ll see a second housing collapse within the decade.”

This is a speculative, predictive claim. It projects future events based on a model of the present.

Mode: Predictive

Evidentiary base: Trend extrapolation, comparison to past patterns

Required qualifiers: Probability, uncertainty, alternative scenarios

Speculative claims require careful modal language:

“May lead to...”

“Could increase the risk of...”

“If current trends continue...”

If presented without such qualifiers, the reader may misinterpret possibility as inevitability.

E. Claims About Morality or Intent (Normative and Interpretive)

“The officials responsible clearly don’t care about middle-class families.”

This is an intent attribution, paired with moral condemnation. It claims knowledge of internal states—what officials feel or value—without direct evidence.

Mode: Normative and psychological

Evidence needed: Statements, policies, or patterns of behavior that could plausibly be interpreted as indifference

Risk: Overstepping evidentiary limits; substituting interpretation for demonstration

Intent claims are inherently speculative unless backed by admissions, documents, or clear patterns. Without such support, they function more as rhetorical leverage than reasoned argument.

6.2 The Seamless Blend: Why It Matters

In real discourse, all these types of claim are often blended together. A reader might encounter the following paragraph:

“Housing starts fell for years while prices soared. Everyone could see the bubble coming, yet regulators sat on their hands. This wasn’t just negligence—it was a betrayal of the public trust. And if they don’t reverse course, we’re heading for another collapse.”

In this short span, at least five modes of claim appear:

Descriptive: “Housing starts fell...”

Causal: “...while prices soared” (implying under-supply pushed prices)

Counterfactual: “Everyone could see the bubble coming”

Evaluative: “This wasn’t just negligence...”

Predictive: “We’re heading for another collapse”

The reader is rarely told to switch modes. Instead, the emotional force and narrative flow carry the argument forward, making each link feel inevitable.

This rhetorical move—presenting different types of claim as if they belonged to a single chain of evidence—is effective, but intellectually hazardous. It discourages:

Modal discrimination: Seeing the difference between what is observed, what is guessed, and what is judged.

Evidentiary discipline: Matching the right kind of support to the right kind of claim.

Cognitive distance: The ability to ask, “Wait—what kind of claim is that, and how do I know it’s true?”

6.3 Further Examples from Real Discourse

Example A: Education Reform

“Our schools are failing. Graduation rates are down. Kids can’t read. Administrators are more interested in diversity than performance. If this continues, the next generation will be unemployable.”

Types of claim:

Descriptive: “Graduation rates are down.”

Evaluative: “Schools are failing.”

Causal/Interpretive: “Administrators are more interested in diversity...”

Predictive: “...next generation will be unemployable.”

To respond intelligently, one must separate each claim, assess what evidence supports it, and ask what assumptions are being made.

Example B: Climate Policy

“The recent floods prove we’re already living in a climate emergency. Politicians who deny the science are endangering lives. If we don’t cut emissions immediately, we’ll face catastrophic collapse.”

Descriptive: “Floods occurred.”

Interpretive: “Prove we’re in a climate emergency.” (Requires scientific attribution studies)

Evaluative/Normative: “Politicians...are endangering lives.” (Moral claim about responsibility)

Predictive: “Catastrophic collapse.”

Blending climate science, political critique, and moral urgency into one rhetorical stream is common—but the claims must be evaluated separately to assess their merit.

Conclusion

Real-world arguments rarely isolate their claims by type. Instead, they present a persuasive fusion of description, analysis, judgment, and projection. The power of these arguments often lies in this seamless blending—but their weakness, logically, lies there too.

The critical reader must:

Disentangle the parts,

Clarify their mode,

Identify what evidence would be needed for each,

And distinguish between what is stated, implied, and assumed.

Failing to do so invites confusion, overconfidence, and the acceptance of persuasive narratives in place of justified conclusions.

7. Missteps in Public Argument

Public discourse is filled with arguments that feel persuasive but falter under scrutiny. These arguments may succeed rhetorically—by resonating with audience beliefs, triggering emotional responses, or appealing to shared intuitions—but they often fail epistemically: that is, they fail to meet the standards of clarity, justification, or logical coherence required for sound reasoning.

The most common errors in public argument are not exotic fallacies or rare logical blunders. They are ordinary habits of sloppy reasoning that pass unnoticed in everyday language. They often stem from haste, rhetorical pressure, or unexamined assumptions, rather than malicious intent. Yet their effect is cumulative: they erode the quality of discourse, mislead audiences, and displace substantive engagement.

This section examines five pervasive missteps, illustrating each with multiple examples and clarifying why they matter.

7.1 Treating Correlation as Causation

The Error: Assuming that because two things occur together, one must have caused the other.

Why It’s a Problem: Correlation means two variables move together, but this does not imply a causal relationship. There may be a third variable causing both, or the association may be coincidental.

Examples:

“Violent video games lead to school shootings.”

– Some shooters have played video games; many millions of people do. No causal link has been reliably established. This ignores the base rate of behavior across populations.“Neighborhoods with more libraries have higher test scores, so building libraries improves education.”

– Higher scores may result from socioeconomic status, which also predicts library access. Libraries may be associated with good outcomes, but not cause them.“When ice cream sales go up, so do drowning incidents.”

– Both are correlated with summer weather, not with each other.

Remedy: When correlation is observed, ask:

What causal mechanism is proposed?

Are alternative causes considered?

Is there longitudinal or experimental evidence?

7.2 Substituting Indignation for Evidence

The Error: Using outrage, moral condemnation, or emotional intensity in place of factual or analytical support.

Why It’s a Problem: Emotional language can signal importance, but it cannot substitute for reasoning. Being angry about an issue does not validate claims about it.

Examples:

“It’s disgusting that corporations are allowed to pollute!”

– This may be a reasonable moral sentiment, but what specifically are they doing, how much pollution is occurring, and under what regulations?“Anyone who supports that policy is complicit in injustice.”

– This shuts down disagreement and skips over the question: Is the policy unjust? What are its effects?“How dare they ignore the community’s needs?”

– The key issue is: Were the needs ignored? What evidence supports that?

Indignation often acts as a rhetorical accelerant, intensifying emotional appeal while bypassing analytic structure.

Remedy:

Translate emotion back into propositions: What exactly is being claimed?

Evaluate whether there is any evidence, or just expressive assertion.

7.3 Making Claims Without Specifying Scope

The Error: Asserting a claim as if it applies universally, when it may only apply in limited cases.

Why It’s a Problem: Scope confusion leads to overgeneralization and misrepresentation. A true statement about some cases may be presented as if it applies to all.

Examples:

“Online education doesn’t work.”

– For whom? Under what conditions? In which subjects?

Perhaps it fails for young children but succeeds for adult learners.“Politicians lie.”

– All politicians? All the time? Or is this a generalization from specific examples?“The justice system is broken.”

– Entirely? In every jurisdiction? For all kinds of cases?“Immigrants are taking jobs from citizens.”

– Where, when, and which jobs? Is the effect local, sector-specific, or anecdotal?

Remedy:

Ask: What is the actual range of the claim?

Insert scope modifiers where appropriate:

“In many cases,” “Among younger students,” “Some critics argue…”

Specificity increases credibility by showing that the argument recognizes limits and variation.

7.4 Ignoring Alternative Explanations

The Error: Presenting one causal story while disregarding other plausible accounts.

Why It’s a Problem: Causal arguments are often underdetermined by the available evidence. Jumping to a preferred explanation without ruling out alternatives is premature.

Examples:

“The rise in crime is due to defunding the police.”

– Perhaps, but what about pandemic-related unemployment, court backlogs, reduced community programs?“Test scores dropped because of the new curriculum.”

– Could be due to changes in testing standards, post-pandemic learning loss, or demographic shifts.“The power outage was caused by renewable energy instability.”

– Or by outdated infrastructure, high demand, or failures in load forecasting?

Remedy:

Actively list and consider alternative explanations, even those that challenge the favored position.

Evaluate whether the preferred explanation is competing, complementary, or insufficient.

This kind of analysis improves robustness and avoids simplistic storytelling.

7.5 Equating Plausibility with Proof

The Error: Believing that because something sounds reasonable or fits a familiar narrative, it must be true.

Why It’s a Problem: Plausibility is shaped by cultural familiarity, emotional resonance, and narrative fit—not by evidentiary strength. Many falsehoods are highly plausible.

Examples:

“It stands to reason that raising the minimum wage causes unemployment.”

– Intuitively plausible to some, but empirical data is mixed and context-dependent.“Of course that company is cutting corners—it’s all about profit.”

– Plausible, but is there evidence? Whistleblower reports? Internal documents?“Obviously, the wealthy use offshore accounts to avoid taxes.”

– Certainly plausible. But how often? Which laws apply? What’s the evidence?“It makes sense that urban density causes higher COVID rates.”

– Appears logical, but data has shown that policies and timing mattered more than density.

Remedy:

Ask: What independent verification supports this idea?

Distinguish between what fits expectations and what has been demonstrated.

Conclusion

Missteps in public argument typically stem from:

Overstated causal claims,

Emotional substitution for reason,

Lack of scope discipline,

Neglect of alternatives,

And the confusion of intuitive plausibility with verification.

These errors are not technical fallacies in the formal sense, but they are practical degradations of argument quality. They make discourse less informative, less reliable, and more vulnerable to manipulation.

Skilled argumentation requires developing habits of:

Precision in claims,

Clarity in scope,

Caution in inference,

And humility in judgment.

The next section turns to the educational implications of these insights—why argumentation is poorly taught and what could be done to improve reasoning skills across disciplines and public life.

8. Improving Argument Education

Understanding and constructing arguments are not disembodied acts of logic. They are rooted in perception, emotion, prior belief, and social engagement. Every act of reasoning begins from somewhere—from what is already known, suspected, hoped for, or feared. There is no “view from nowhere,” no purely neutral stance from which one might assess arguments with perfect detachment. Instead, argument is always situated, filtered through the limitations of one’s understanding, the pull of one’s biases, and the shaping influence of one’s cultural and social environment.

Yet most curricula treat argumentation, if at all, as either a matter of style (rhetoric) or form (the five-paragraph essay). These approaches fail to address the deep cognitive and epistemic demands of good reasoning. They teach students how to make their writing look persuasive—with thesis statements, topic sentences, and smooth transitions—but not how to build arguments that are clear, sound, or epistemically responsible.

8.1 The Situated Nature of Argument

Before reforming education, it must be recognized that argumentation is not merely a technical skill. It is a human act, shaped by:

Cognitive limitations: People often overestimate what they know. Confidence is not correlated with accuracy. The illusion of explanatory depth—believing one understands something better than they do—is well documented (Rozenblit & Keil, 2002).

Emotional valence: Beliefs are emotionally charged. Challenges to belief can feel like attacks on identity. Reasoning often follows emotion, not the other way around.

Social embeddedness: Arguments are often crafted not to discover truth, but to persuade, signal group membership, or defend status. Understanding itself is often negotiated socially—through conversation, criticism, and shared frameworks. In this sense, understanding is indeed a social act.

Bias and blind spots: Confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, availability heuristics, and cultural framing distort even sincere reasoning. These are not exceptions to rationality—they are its default context.

Good argumentation, then, is not the natural mode of human thought. It is an acquired discipline, and a hard one at that. It demands attention to distinctions that the mind would rather blur, to alternatives that the ego would rather ignore.

8.2 The Difficulty of Learning to Argue Well

Learning to argue well is hard for at least three reasons:

The Skill Is Composite

Argumentation is not a single ability. It draws on:Language mastery,

Conceptual analysis,

Epistemic self-awareness,

Logical reasoning,

Ethical sensibility,

Audience awareness.

No single component is sufficient. All must work together. This makes argumentation a high-order integration skill, like composing music or designing a scientific experiment.

The Feedback Loop Is Weak

In most domains, poor performance yields immediate consequences. In argumentation, bad arguments may be rewarded if they are rhetorically effective. Without reliable feedback, errors become habits. Students learn that confidence, fluency, or passion substitute for substance.Instruction is Largely Absent

Formal training in argument structure, epistemic clarity, and reasoning modes is rare outside a few disciplines (philosophy, law, debate). Even where critical thinking is taught, it is often decontextualized—presented as isolated puzzles or fallacy spotting, not as a living skill applied to real discourse.

Given this landscape, it is unsurprising that argumentation is rarely mastered. It is difficult, cognitively demanding, and institutionally neglected.

8.3 What a Reformed Curriculum Might Include

To teach argument well, instruction must go beyond grammar and style to include reasoning structure, evidentiary analysis, and epistemic discipline. Some essential components might include:

1. Training in Modal Recognition

Students must learn to recognize what kind of claim is being made:

Is it descriptive (about what is)?

Predictive (about what will be)?

Evaluative (about what is good or bad)?

Normative (about what should be)?

Counterfactual (about what could have been)?

Each mode requires a different type of support. Failing to distinguish them leads to modal confusion, as when a moral claim is defended with data, or a prediction is treated as if it were a fact.

Example Exercise: Analyze an editorial and label each sentence by mode. Discuss what kind of evidence would support each.

2. Practice in Adversarial Paraphrase

Rather than restating a claim in agreeable terms, students are asked to restate it as a critic would. This forces attention to ambiguity, hidden assumptions, and multiple readings.

Example:

Original: “The city failed its residents during the storm.”

Adversarial paraphrase: “The author claims that all consequences of the storm were preventable and that municipal actors bear exclusive blame.”

This practice helps surface unstated premises and clarify interpretive vulnerability.

3. Instruction in Lines of Evidence and Cumulative Argument

Arguments should not depend on one point alone. Students should learn to structure arguments around independent lines of evidence, each of which converges on the conclusion without depending on the others.

Atomic evidence: A single data point (e.g., “Police response time exceeded 12 minutes last Tuesday”).

Lines of evidence: Multiple sources (e.g., reports, statistics, expert analysis).

Cumulative argument: Even if each line is imperfect, the overall case may become compelling.

Example:

Claim: “The city’s infrastructure is deteriorating.”

Evidence lines:

Reported sinkhole incidents increased.

Road maintenance budgets cut for five years.

Resident complaints about broken sidewalks.

Students must assess how these threads relate and what weight each adds to the total case.

4. Identification of Rhetorical Contamination

Students must learn to detect when emotive language, loaded terms, or figurative flourishes interfere with reasoning. This is not to ban rhetoric, but to teach how to separate signal from noise.

Examples of rhetorical contamination:

“Taxpayers are being mugged by their own government.” (Loaded metaphor)

“Only a fool would support this policy.” (Ad hominem implication)

“Our children’s future is being auctioned off.” (Dramatic hyperbole)

Exercise: Rewrite a paragraph with rhetorical coloration removed. Compare the underlying claim to the original surface effect.

8.4 The Aim: Disciplined Thought, Not Just Polished Prose

The goal of argument instruction is not just to make writing sound better, but to make thinking more rigorous. Well-structured arguments:

Distinguish types of claims,

Match support to mode,

Recognize their assumptions,

Address likely objections,

Avoid conflating persuasion with proof.

Such writing is often less dramatic, but it is more trustworthy. It is harder to produce, but more useful to read.

Conclusion

The failure to teach argument well is not just a gap in the curriculum—it is a missed opportunity to cultivate disciplined thought in a society awash in persuasion. Argument is not a rhetorical trick or a stylistic flourish. It is a core method by which we test our beliefs, engage others, and learn to see through error—especially our own.

But it is hard. It demands the recognition that we begin in ignorance, that we are easily misled, and that good reasoning is a skill earned, not assumed. That recognition is the beginning of epistemic humility—and of meaningful education in argument.

The next section will provide a summary of the major themes of this treatise and restate the practical importance of improving how arguments are read, made, and evaluated in real discourse.

Summary

Constructing and analyzing arguments in real-world settings demands far more than familiarity with formal logic or fluency in rhetorical technique. It requires a deliberate, sustained awareness of the nature of each claim, the strength and relevance of its supporting evidence, and the reasoning structure that links assertion to conclusion. Most arguments encountered in public discourse are not logically explicit. They are constructed in natural language, which tends to blur distinctions, conceal transitions, and favor persuasive surface over analytical substance.

Natural language masks the difference between observation and interpretation, between conjecture and judgment, between what is described, what is inferred, and what is valued. As a result, readers and listeners must actively reconstruct the underlying logic, identify epistemic modes, separate rhetorical flourishes from argumentative substance, and assess how evidence is arranged—whether it comes as isolated facts, converging lines, or cumulative approximations.

These interpretive strategies are not innate. They are difficult, cognitively demanding, and often absent from formal education. Yet they are essential. Without them, arguments are accepted or rejected based on intuition, emotional resonance, or ideological alignment rather than structured evaluation.

Reasoning well, then, is not merely a matter of intelligence or eloquence. It is a discipline of clarity: the ability to recognize the kind of claim being made, to calibrate one’s confidence to the quality of evidence, and to organize that evidence coherently. These are learnable—but seldom taught—and rarely mastered.

A culture that values sound reasoning must take seriously the need to teach these skills explicitly, deliberately, and contextually. The quality of public discourse depends on it.

Annotated Reading List (APA Format)

Toulmin, S. (2003). The Uses of Argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge University Press.

— Introduces the Toulmin model of practical reasoning. Useful for understanding how real-world arguments differ from formal logic.

Govier, T. (2010). A Practical Study of Argument (7th ed.). Wadsworth.

— A comprehensive introduction to evaluating everyday arguments, with examples and exercises.

Fisher, A. (2004). The Logic of Real Arguments (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

— Focuses on argument evaluation in context, with detailed analysis of messy, non-idealized discourse.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

— While not about argumentation per se, this book explains many of the cognitive biases that shape how people argue and interpret arguments.

Walton, D. (2006). Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation. Cambridge University Press.

— Examines informal reasoning and argumentation schemes. Offers a typology for analyzing arguments.

Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2012). Argumentation and Critical Decision Making (8th ed.). Pearson.

— A practical guide to critical thinking and structured decision-making.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2014). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts and Tools. Foundation for Critical Thinking.

— A brief, accessible primer on reasoning, including how to distinguish kinds of claims and modes of thinking.