Reason: Knots and Tangles

There may be more to them than you'd suspect

Introduction

Knots and tangles. Simple things, or so they seem. Every child learns to tie their shoes. Every camper learns to secure a line. Every sailor, climber, or craftsman knows that a good knot can make the difference between safety and disaster. But knots are more than just practical tools. They are the product of reason, visualization, physical principles, and centuries of human experience. They represent an intricate interplay between intellect and material, between abstraction and hands-on skill. Tangles, on the other hand, are something altogether different. They seem to arise spontaneously, as if by some malevolent force, defying reason, slipping beyond intention and comprehension.

In this essay, we will look at knots from many perspectives: practical, mathematical, psychological, physical. We will explore the arcane language of knots, the pragmatic criteria that define them, and the curious fact that some people can tie and untie knots effortlessly while others struggle. We will wonder whether other animals can tie knots. We will reflect on the strange fact that while humans have crafted an entire mathematical theory of knots; it does not necessarily follow that those who study it would be able to tie a reef knot to save their lives. And we will consider the importance of learning knots from those who have practiced them in the field, where success—or survival—depends on getting it right.

Discussion

1 - Knots vs. Tangles

At the simplest level, we can distinguish between knots and tangles. Knots are deliberate, intentional constructs. Human beings create knots. They tie them to secure loads, connect objects, or create decorative or useful patterns. Knots have purpose, structure, and design.

Tangles, however, are something else entirely. Leave cords, wires, strings, or lines in a box or a drawer, and in time you will find them hopelessly snarled. Tangles just appear mysteriously, with no conscious effort at all. How they come into existence is something of a puzzle. They seem to violate basic common sense. And yet there they are, a mass of confusion, an impossible mess. Untangling them? That can be a feat of genius, requiring patience, dexterity, and an almost mystical insight into the workings of string. It’s easy to imagine they are the work of demons or malign forces—something outside the bounds of ordinary reason. Knots may be mysterious, but tangles are downright uncanny.

2 - Knots Learned for Pragmatic Purposes

The study of knots is an ancient and practical art. From the earliest days of human history, knots have been essential tools. Hunters, gatherers, and sailors depend on them for survival. Youth organizations like the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides have long taught knot tying as a basic skill. There were—and still are—badges awarded for competence in knots. You might learn how to tie a square knot, a bowline, a clove hitch. You might understand how it works, what it’s for. But can you replicate it the next day? What about ten years from now? Without practice, memory fades. The muscle memory weakens. The knowledge needs refreshing, at the very least.

In the pragmatic world, knots serve different purposes. Each trade and profession has developed its own set of preferred knots. Seafarers favor some, climbers others, hunters still others. There’s no universal best knot—different knots for different jobs. Some are designed to hold fast under tension. Some are made to be untied easily, even after bearing a heavy load. Some must not slip; others must slide freely when needed. The criteria for each vary, and mastering them is a serious business. Some people learn knots as a hobby. Others do so because their livelihoods or lives depend on it.

3 - Physics of Knots

Behind every knot is a foundation in physical principles. This isn’t theoretical physics but everyday, pragmatic understanding. A good knot depends on dimensions, lengths, textures, friction, braiding, composition, strength, flexibility, and stiffness. It relies on fundamental facts—two solid objects can’t occupy the same space at the same time. Yet a rope can pass through air, around an object, and back through a loop, creating structures that hold.

Friction is key. Why don’t knots come undone? Friction between the rope’s fibers holds them in place. Tension makes the knot tighten under load. But that same friction can make a knot difficult—or impossible—to untie later. Multiple ropes may tighten unevenly; some ropes bear too much tension while others hang slack. Improper knots may slip, unraveling with potentially disastrous results. Others, when improperly tied, may jam and be impossible to release. Understanding how material behaves—how ropes stretch, how they resist or yield—is essential to the craft.

And there’s the curious fact that sometimes things are open, and sometimes they are closed. A loop may look like a hole, but it’s actually a boundary. Knowing when and where to pass the line through that opening, and how to keep it open or closed at the right moment, is part of knot craft.

4 - Mathematical Theory of Knots

Beyond the hands-on world of practical knots, there is a mathematical theory of knots. Topology, they call it. An abstract, theoretical study of knots, far removed from seafaring or mountaineering. Topologists—those mathematicians—have created elaborate descriptions of knots and formal systems to classify them. They have worked out equivalences and invariants, found ways to distinguish one knot from another no matter how they are twisted or stretched.

And strangely enough, this mathematical work has found applications beyond tying ropes. Knot theory has been used in molecular biology, in the study of DNA and protein folding. It appears in physics, in the study of fields and particles. Whether these theorists can actually tie a bowline is another matter entirely. Some may be good at it. Probably not all.

6 - Psychology of Knots

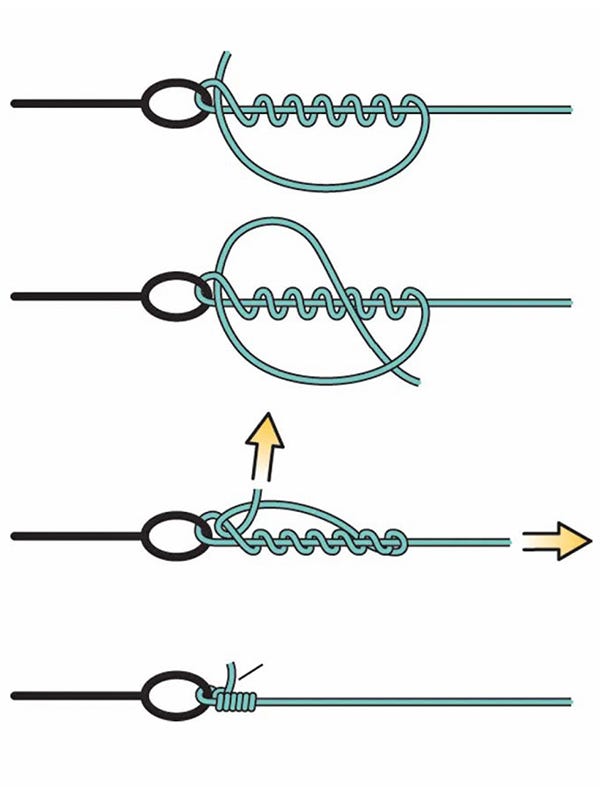

There’s a psychology to knots as well. Learning to tie a knot requires visualization—seeing not just what your hands are doing, but how the structures form and move in space. Words can help, up to a point. Diagrams help more. But at some level, you have to understand the knot in a way that words and pictures can’t fully convey. It is visual perception and cognition, perceptual-motor skill and memory.

Is this ability unique to human beings? It’s an open question. Some animals are excellent at manipulating their environments. Birds build nests. Beavers build dams. Spiders spin webs. Some of these structures are elaborate, even beautiful. But are they knots? Or are they something else—structures without the intentional, closed-loop characteristics we associate with knotting?

One wonders whether creatures like orangutans could learn to tie knots. Corvids—crows and ravens—are known for their cleverness. Could they grasp knots? Perhaps. But not all humans have the capability. Some people struggle with knots their entire lives. And certain forms of neurological damage can rob a person of the ability to tie or untie knots entirely. Knot craft requires certain neurological equipment, specific mental faculties of spatial reasoning and motor control.

7 - Language of Knots

Knots have their own language. Bights and bends. Hitches and loops. Simple knots, double knots, reef knots. The terminology is arcane, understood by specialists, baffling to the uninitiated. It’s a language that must be studied. And like all technical languages, it reflects the underlying structure of the craft. Each term identifies a concept or a technique that may be essential for understanding and mastering the work.

And there’s always room for new knots. There are ad hoc knots—improvised solutions for specific problems. They may or may not be good enough to keep. There are ad hoc knots, worked out on the spot but following established principles. And there are structured knots, formal and traditional, passed down through generations of practitioners.

8 - Videos and Instructional Materials on Knot Craft

Instruction is where knowledge becomes skill. And the best instruction often comes from an old hand—someone who has worked with knots in the field. Whether it’s seafaring, boating, hunting, camping, mountain climbing, needlework, knitting, crochet—each has its own body of knot knowledge. You can learn a vast number of knots. You probably won’t learn them all. And you can always invent more.

Videos and books provide valuable instruction. Diagrams and slow-motion demonstrations make complex knots easier to grasp. But there’s no substitute for hands-on guidance, for the voice of experience. Listen closely to the old hands. You might need that knowledge someday—just the right knot for just the right purpose, at just the right time.

If you try to secure a load and you don’t know your knots, you’re asking for trouble. Some ropes will be too tight, some too loose. Some knots will slip and come undone; others will jam and refuse to release when you need them to. A poorly tied load may fall apart as you drive, causing disaster—or worse. It has happened. The stakes can be life and death.

Summary

Knots. They seem simple, but they’re anything but. Knots are the product of human reason, visualization, and craft. They are grounded in physics, structured by mathematics, could be studied through psychology, and taught in languages of their own. Knots serve practical purposes, but they also reveal something deeper about how we understand and manipulate the world.

Tangles are a different story. They arise without cause, defy intention, and resist reason. They remind us that not everything can be ordered, that some things remain mysterious.

So study your knots. Practice them. Learn from those who know. Understand their purpose, their physics, their language. And remember: someday, the right knot might make all the difference.