Large Language Models, Scholarship, and the Future of Intellectual Work

I have ChatGPT present my self-serving case. To what extent am I correct?

Introduction

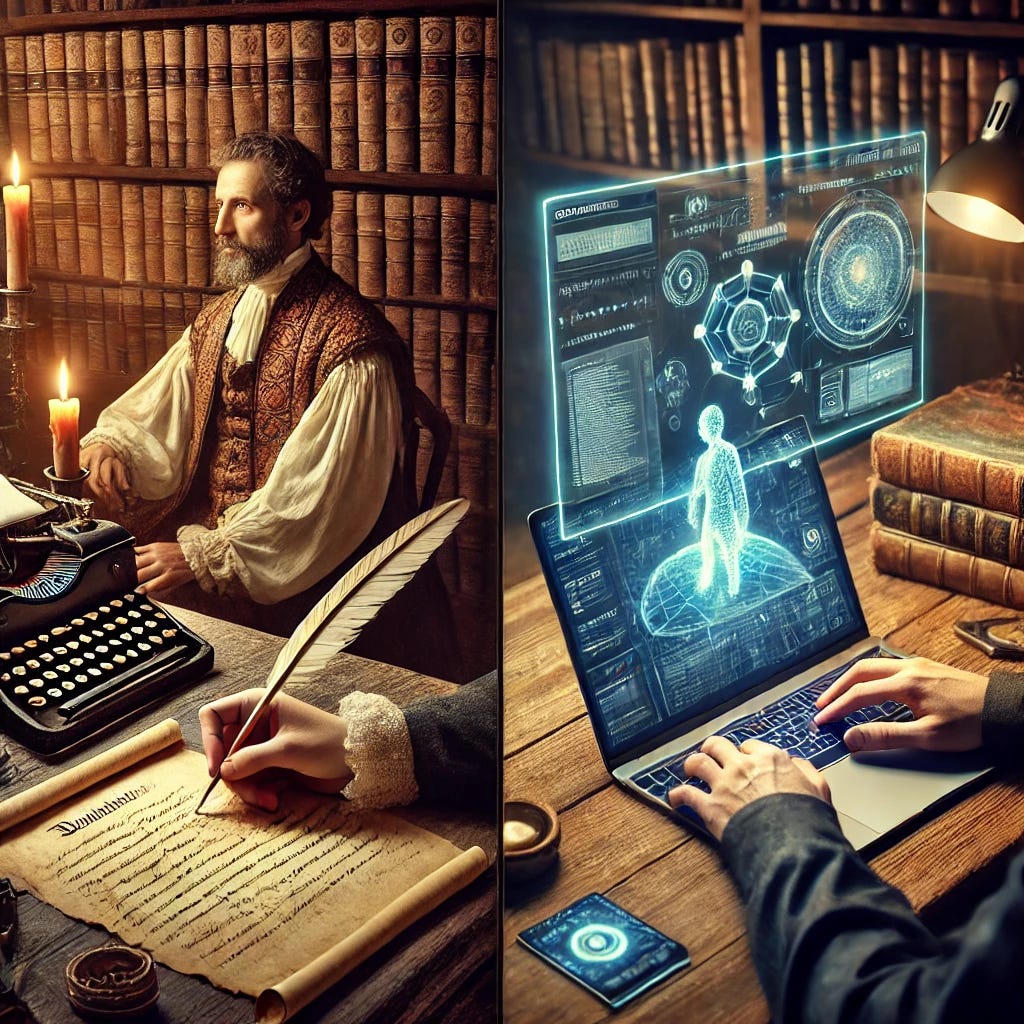

Humans are tool users—more than any other species, our history has been defined by the development and use of tools to extend our capabilities. Now, we face an entirely new kind of tool: Large Language Model Artificial Intelligence (LLM-AI). It is a mysterious, flawed, yet highly useful tool when used appropriately. The real question is: what does “appropriately” mean in the context of research, scholarship, and intellectual work?

With LLM-AI, we are witnessing a fundamental shift in how knowledge is accessed, synthesized, and presented. This shift has triggered an intense emotional reaction and counter-reaction, with many being dragged kicking and screaming into this new reality. However, much of the debate is muddled by a failure to distinguish between purpose, process, and result—three essential aspects that too often get blurred.

The Changing Nature of Scholarship

The purpose of scholarship has evolved over time, but in modern academia, it has traditionally focused on learning, reasoning, and demonstrating understanding. Students were expected to research information, structure arguments, and craft essays as a means of developing their ability to think critically and communicate effectively. The actual product of their work had little intrinsic value beyond serving as evidence of their competence in the process.

In recent years, this model has deteriorated. The abomination of multiple-choice testing has largely replaced essay-writing in many educational settings, reducing the emphasis on structured reasoning and written argumentation. Nevertheless, for those still engaging in the traditional model, the process of researching, analyzing, and crafting ideas into a coherent written form has remained a fundamental exercise.

Scholars, by contrast, had different motivations. Their work was not merely a demonstration of competence, but an attempt to advance knowledge—whether for intellectual progress, career advancement, or professional prestige. They were expected to engage with primary sources, conduct original research, and contribute meaningfully to the broader body of knowledge. However, much of what passed for scholarship was ultimately opinion and interpretation, even if scholars preferred not to acknowledge that reality.

The Advent of Large Language Models

With the emergence of LLM-AI, the traditional model of research and writing has been turned upside down. Instead of searching for sources and painstakingly assembling arguments, a student (or scholar) can reverse the process, starting with a prompt and having the AI generate fully formed text. The user can then refine the output by adjusting prompts or requesting rewrites until they achieve a satisfactory result.

However, LLM-AI lacks insight. It does not reason, interpret, or evaluate—it simply produces text based on statistical associations within its training data. This dataset, while extensive, is a mix of fact, opinion, propaganda, and interpretation, all of which have been interwoven in ways that are not clearly distinguishable.

The developers of LLM-AI are often opaque about their data sources, and legal disputes are ongoing over the provenance of the material used to train these models. Unlike traditional research, where sources can be explicitly cited and scrutinized, LLM-AI offers no clear traceability for most of its outputs. While some newer models attempt to integrate internet search for reference retrieval, these searches are often approximate, unreliable, and prone to presenting surface-level results rather than deep insights.

The Problem of Reliability and the Risk of Being Hornswoggled

Because LLM-AI lacks understanding, its outputs are only as good as the user’s ability to critically evaluate them. A knowledgeable user can prompt an LLM to generate insightful and well-structured content, while an uncritical user can produce utter nonsense without realizing it. This is true for both students and scholars—human users can generate brilliant work or completely misguided work depending on how they approach the process.

LLM-AI, however, is just a computational algorithm with a pseudorandom component, assembling text through associative chains of weighted probabilities. It does not assess truth, validity, or logical coherence—it merely produces plausible-sounding language. As a result, those who rely on it blindly, especially without subject-matter expertise, can easily be hornswoggled into believing its outputs are authoritative when they may, in fact, be riddled with inaccuracies, misinterpretations, or outright fabrications.

Conclusion

The arrival of LLM-AI in scholarship and intellectual work is inevitable, but its use remains highly contested. Much of the opposition is not based on a clear-eyed assessment of its strengths and weaknesses, but rather on an emotional resistance to new tools—a pattern that has repeated throughout history whenever transformative technologies have emerged.

At the heart of the debate is a fundamental question: What does it mean to use LLM-AI "appropriately"? This question cannot be answered without first distinguishing between purpose, process, and result—three aspects that many critics and defenders alike fail to separate.

If the goal of scholarship is to advance human understanding, then LLM-AI must be used as a tool for thinking, not a replacement for thought. Tools exist to save time and improve results, and LLM-AI is no different. However, just as with any tool, its effectiveness depends on the skill and discernment of the user. Those who use it with care, critical thinking, and an understanding of its limitations will find it to be an invaluable aid. Those who do not will continue to be hornswoggled—not because of laziness, but because they failed to recognize the fundamental nature of the tool they were using.